Alabama Department of Mental Health

Alabama Department of Mental Health Logo

Headquartered in Montgomery, the Alabama Department of Mental Health (ADMH) is the state agency charged with providing care, treatment, and support services to people with mental illnesses, developmental disabilities, and substance use disorders. It was founded in 1965 to enhance the state’s delivery of mental health services. ADMH is headed by a commissioner appointed by the governor and is comprised of three service areas—the Division of Administration, the Division of Developmental Disabilities; and the Division of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. The department is organized under the Commissioner’s Office with special services and administrative support at the central office in Montgomery. Six regional offices assist families with issues related to intellectual disability services. Although most individuals with mental illnesses receive services through community providers, the department also operates the Mary Starke Harper Geriatric Psychiatry Center, the Taylor Hardin Secure Medical Facility, and Bryce Hospital in Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County.

Alabama Department of Mental Health Logo

Headquartered in Montgomery, the Alabama Department of Mental Health (ADMH) is the state agency charged with providing care, treatment, and support services to people with mental illnesses, developmental disabilities, and substance use disorders. It was founded in 1965 to enhance the state’s delivery of mental health services. ADMH is headed by a commissioner appointed by the governor and is comprised of three service areas—the Division of Administration, the Division of Developmental Disabilities; and the Division of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. The department is organized under the Commissioner’s Office with special services and administrative support at the central office in Montgomery. Six regional offices assist families with issues related to intellectual disability services. Although most individuals with mental illnesses receive services through community providers, the department also operates the Mary Starke Harper Geriatric Psychiatry Center, the Taylor Hardin Secure Medical Facility, and Bryce Hospital in Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County.

The origins of the present-day ADMH date back to the establishment of the Alabama Insane Hospital in 1852 by the Alabama State Legislature and Gov. Henry W. Collier. During the early years of Alabama‘s statehood, in the state and in much of the nation the mentally ill were either cared for privately or kept locked in rooms or otherwise restrained, usually depending upon family income. During the 1840s, however, mental health crusader Dorothea Dix travelled the nation working to create hospitals and other facilities to treat the mentally ill in more humane ways. She visited Alabama during that period, and her efforts, along with those of the Alabama Medical Society (now the Medical Association of the State of Alabama), were the impetus for the state’s new legislation establishing the hospital. The Alabama Insane Hospital, designed by architect Thomas Kirkbride, was completed in 1859 in Tuscaloosa.

The facility’s board of trustees hired physician Peter Bryce in 1861 to serve as the first superintendent. Bryce eliminated the use of seclusion and restraints as a standard practice and adhered to a treatment philosophy centered on providing a peaceful environment filled with structured activities. In the 1870s and 1880s, the hospital underwent significant expansion with the addition of wings on either side of the main building that raised the hospital’s capacity to more than 700 patients. Therapeutic farm work by patients allowed the hospital to raise operating funds through the sale of produce. Bryce Hospital also had its own coal mine, power plant, dairy, and laundry and was basically a self-sufficient community.

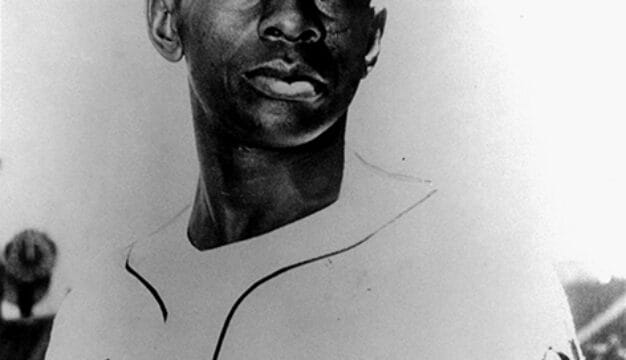

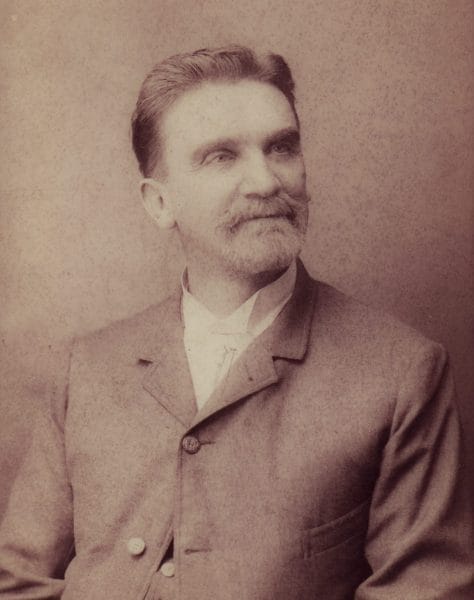

Peter Bryce

Bryce died in 1892 and was succeeded by physician James Thomas Searcy, who continued many of the reforms instituted in the Bryce era. The hospital’s patient population continued to increase, however, and by the turn of the twentieth century, the hospital was beginning to suffer from overcrowding. In 1900, in response, the Alabama State Legislature approved the establishment of a second hospital in Mount Vernon, Mobile County, on the campus of the former Mount Vernon Arsenal. Originally called Mount Vernon Hospital, it was renamed Searcy Hospital in 1919 in Searcy’s honor. The facility eventually housed only African American patients until it was desegregated in 1965. In 1922, under the direction of Superintendent William D. Partlow, the Alabama Home for Mental Defectives was constructed near the campus of Bryce Hospital. The facility housed people who were intellectually disabled but not mentally ill because Partlow understood that these populations would be better served in different settings. The institution was renamed in Partlow’s honor in 1927 as the Partlow State School and later the W. D. Partlow Developmental Center. The facility closed permanently in December 2011.

Peter Bryce

Bryce died in 1892 and was succeeded by physician James Thomas Searcy, who continued many of the reforms instituted in the Bryce era. The hospital’s patient population continued to increase, however, and by the turn of the twentieth century, the hospital was beginning to suffer from overcrowding. In 1900, in response, the Alabama State Legislature approved the establishment of a second hospital in Mount Vernon, Mobile County, on the campus of the former Mount Vernon Arsenal. Originally called Mount Vernon Hospital, it was renamed Searcy Hospital in 1919 in Searcy’s honor. The facility eventually housed only African American patients until it was desegregated in 1965. In 1922, under the direction of Superintendent William D. Partlow, the Alabama Home for Mental Defectives was constructed near the campus of Bryce Hospital. The facility housed people who were intellectually disabled but not mentally ill because Partlow understood that these populations would be better served in different settings. The institution was renamed in Partlow’s honor in 1927 as the Partlow State School and later the W. D. Partlow Developmental Center. The facility closed permanently in December 2011.

Bryce Hospital

During the Great Depression and into the 1950s, mental health care across the nation, including Alabama, was typically underfunded, and care for patients became more and more difficult with aging facilities, scarce resources, and inadequate staff. To help address these issues, in 1965 the Alabama Legislature created the Alabama Department of Mental Health by Act 881 and gave broad authority to the commissioner. In 1967, Gov. Lurleen Wallace toured the facilities at Bryce and was so disturbed by conditions, she urged the state legislature to raise funding levels. Despite efforts to improve infrastructure and care levels, mental health facilities and programs in the state continued to be inadequate. By 1970, Bryce Hospital had more than 5,000 patients but only three psychiatrists. That same year, in response to funding cuts, staff at Bryce was reduced to hazardous and unacceptable levels, and attorneys filed a lawsuit in state court on behalf of the employees. The case was transferred to federal court in 1971 as a “human rights” case on behalf of a former patient. The federal case, known as Wyatt v. Stickney, became the longest running mental health case in history. After reaching the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, the case was decided in favor of the plaintiffs on November 8, 1974, setting enforceable minimum standards of care and treatment for patients in Alabama’s state-run facilities.

Bryce Hospital

During the Great Depression and into the 1950s, mental health care across the nation, including Alabama, was typically underfunded, and care for patients became more and more difficult with aging facilities, scarce resources, and inadequate staff. To help address these issues, in 1965 the Alabama Legislature created the Alabama Department of Mental Health by Act 881 and gave broad authority to the commissioner. In 1967, Gov. Lurleen Wallace toured the facilities at Bryce and was so disturbed by conditions, she urged the state legislature to raise funding levels. Despite efforts to improve infrastructure and care levels, mental health facilities and programs in the state continued to be inadequate. By 1970, Bryce Hospital had more than 5,000 patients but only three psychiatrists. That same year, in response to funding cuts, staff at Bryce was reduced to hazardous and unacceptable levels, and attorneys filed a lawsuit in state court on behalf of the employees. The case was transferred to federal court in 1971 as a “human rights” case on behalf of a former patient. The federal case, known as Wyatt v. Stickney, became the longest running mental health case in history. After reaching the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, the case was decided in favor of the plaintiffs on November 8, 1974, setting enforceable minimum standards of care and treatment for patients in Alabama’s state-run facilities.

Taylor Hardin Secure Medical Facility

Unable to comply with the prescribed standards of care because of lack of funding, the state released almost half of its patients. In 1974, however, the Greil Memorial Psychiatric Hospital was opened in Montgomery as an in-patient facility for the mentally ill in the southern half of the state, and in 1977 the North Alabama Regional Hospital was opened in Decatur to serve the northern half. During the 1980s and into the 1990s, Alabama’s mental health facilities were placed under federal supervision for repeated violations of minimum care standards. During this period, the Taylor Hardin Secure Medical Facility was established in 1981 at the Bryce Hospital complex in Tuscaloosa to house people declared criminally insane, and the Mary Starke Harper Geriatric Psychiatry Hospital, a separate facility on the same campus, was established in 1996. It provided an additional 100 beds for inpatient geriatric care. In 2010, the state sold the campus of Bryce Hospital to the University of Alabama and moved all the patients to a new facility that retained the original name.

Taylor Hardin Secure Medical Facility

Unable to comply with the prescribed standards of care because of lack of funding, the state released almost half of its patients. In 1974, however, the Greil Memorial Psychiatric Hospital was opened in Montgomery as an in-patient facility for the mentally ill in the southern half of the state, and in 1977 the North Alabama Regional Hospital was opened in Decatur to serve the northern half. During the 1980s and into the 1990s, Alabama’s mental health facilities were placed under federal supervision for repeated violations of minimum care standards. During this period, the Taylor Hardin Secure Medical Facility was established in 1981 at the Bryce Hospital complex in Tuscaloosa to house people declared criminally insane, and the Mary Starke Harper Geriatric Psychiatry Hospital, a separate facility on the same campus, was established in 1996. It provided an additional 100 beds for inpatient geriatric care. In 2010, the state sold the campus of Bryce Hospital to the University of Alabama and moved all the patients to a new facility that retained the original name.

New Bryce Hospital

In 2011, newly elected Alabama governor Robert J. Bentley appointed Zelia Baugh, a former administrator at the University of Alabama at Birmingham‘s Center for Psychiatric Medicine, as the new commissioner of ADMH. She merged the mental illness and substance abuse service divisions under one associate commissioner to facilitate a more seamless overarching service system, given that more than 70 percent of individuals with serious and persistent mental illnesses also have substance use disorders. In 2012, the state closed Searcy Hospital. In 2020, Gov. Kay Ivey announced the creation of three 24-hour crisis care centers in the state in Mobile, Montgomery, and Huntsville. The centers are intended to provide services and responses to mental health crises that are most often handled by police and hospitals.

New Bryce Hospital

In 2011, newly elected Alabama governor Robert J. Bentley appointed Zelia Baugh, a former administrator at the University of Alabama at Birmingham‘s Center for Psychiatric Medicine, as the new commissioner of ADMH. She merged the mental illness and substance abuse service divisions under one associate commissioner to facilitate a more seamless overarching service system, given that more than 70 percent of individuals with serious and persistent mental illnesses also have substance use disorders. In 2012, the state closed Searcy Hospital. In 2020, Gov. Kay Ivey announced the creation of three 24-hour crisis care centers in the state in Mobile, Montgomery, and Huntsville. The centers are intended to provide services and responses to mental health crises that are most often handled by police and hospitals.