A. G. Gaston

A. G. Gaston

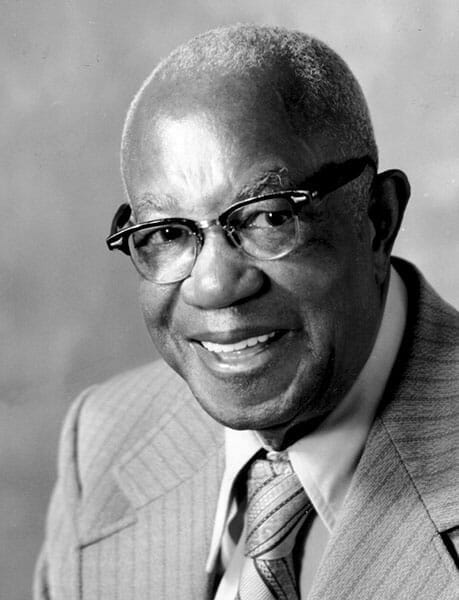

Birmingham entrepreneur and businessman A. G. Gaston (1892-1996), was one of the most successful African American business owners in Alabama. Gaston overcame humble beginnings and racial discrimination to build a $40 million business empire, which included a savings and loan bank, business college, construction company, motel, real estate business, burial insurance company, two cemeteries, and two radio stations. Although criticized for what some viewed as an accommodationist attitude during the Birmingham civil rights movement in the 1960s, Gaston nevertheless used his accumulated wealth to provide financial support to the movement’s leaders and participants at crucial times and worked behind the scenes to help the movement achieve its goals.

A. G. Gaston

Birmingham entrepreneur and businessman A. G. Gaston (1892-1996), was one of the most successful African American business owners in Alabama. Gaston overcame humble beginnings and racial discrimination to build a $40 million business empire, which included a savings and loan bank, business college, construction company, motel, real estate business, burial insurance company, two cemeteries, and two radio stations. Although criticized for what some viewed as an accommodationist attitude during the Birmingham civil rights movement in the 1960s, Gaston nevertheless used his accumulated wealth to provide financial support to the movement’s leaders and participants at crucial times and worked behind the scenes to help the movement achieve its goals.

Arthur George (A. G.) Gaston was born on July 4, 1892, in Demopolis, Marengo County, to Tom and Rosa Gaston. Gaston spent his early childhood living with his grandmother in Demopolis because his father, a railroad worker, died soon after his birth and his mother worked as a family cook for A. B. Loveman, a wealthy Jewish businessman, 25 miles away in Greensboro. Although his grandmother lived in poverty, Gaston nevertheless began to develop his entrepreneurial skills early in life by charging neighborhood children admission in the form of pins or buttons for the privilege of playing on the swing in his grandmother’s yard—the only one in the neighborhood. At the age of 13, Gaston rejoined his mother when she accompanied the Lovemans to Birmingham in 1905. Loveman, who founded the state’s largest department store, was a successful entrepreneur and investor and undoubtedly made an impression on young Gaston.

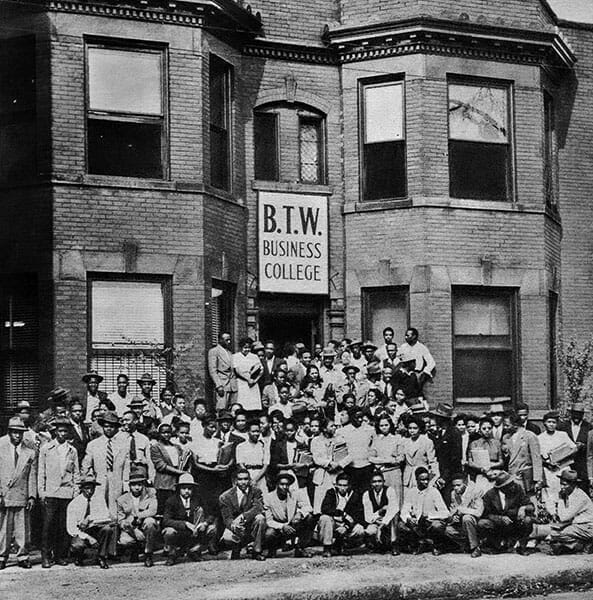

Booker T. Washington Business College

Soon after arriving in Birmingham, Gaston’s mother enrolled him in the Tuggle Institute, a privately run charitable school for African Americans founded by Eufaula native and education and legal reformer Carrie Tuggle in 1903. The Tuggle Institute had adopted Booker T. Washington’s industrial educational philosophy, which emphasized the skilled trades and business. Washington, who visited the school often to make inspirational speeches to the students, quickly became Gaston’s role model. Inspired by Washington’s message of individual initiative, Gaston grew restless and left the Tuggle Institute after completing the tenth grade. He held odd jobs, including selling subscriptions to the Birmingham Reporter, a black-owned newspaper founded in 1906 by Oscar W. Adams, and working as a bellman at the Battle House Hotel in Mobile.

Booker T. Washington Business College

Soon after arriving in Birmingham, Gaston’s mother enrolled him in the Tuggle Institute, a privately run charitable school for African Americans founded by Eufaula native and education and legal reformer Carrie Tuggle in 1903. The Tuggle Institute had adopted Booker T. Washington’s industrial educational philosophy, which emphasized the skilled trades and business. Washington, who visited the school often to make inspirational speeches to the students, quickly became Gaston’s role model. Inspired by Washington’s message of individual initiative, Gaston grew restless and left the Tuggle Institute after completing the tenth grade. He held odd jobs, including selling subscriptions to the Birmingham Reporter, a black-owned newspaper founded in 1906 by Oscar W. Adams, and working as a bellman at the Battle House Hotel in Mobile.

Unable to find fruitful business opportunities, Gaston enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1913. The armed forces were segregated at the time, and Gaston was assigned to the all-black Ninety-second Infantry Division, which was deployed overseas to Cherbourg, France, for combat in 1917 during World War I. Although he was overseas fighting in a war, Gaston managed to consistently send home $15 of his $20 in monthly pay toward a mortgage on his first real estate investment in Birmingham.

Upon returning to Alabama after the war, Gaston drove a delivery truck for a dry-cleaning company and worked as a miner for Tennessee Coal and Iron Company in Fairfield, just outside Birmingham. Always looking for a way to make an extra dollar, Gaston was soon selling homemade sandwiches to his fellow miners at lunchtime. Gaston was able to save a remarkable two-thirds of his income, and with the additional money from his lunch business, he had enough cash on hand to begin lending money to his co-workers at the rate of 25 percent interest.

In 1923, tiring of toiling in the coal mines and seeing a need among poor blacks for more affordable funerals, Gaston founded his first business, the Booker T. Washington Burial Society. In its early years, the society worked much like a fraternal order, with members paying weekly fees of $0.25 that entitled them to burial services upon their death. This business thrived as a result of Gaston’s ability to form a coalition with area black ministers, who steered members of their congregations to the society. He also attracted customers by sponsoring gospel singers and Alabama’s first radio program aimed at African Americans. The society’s success led Gaston to establish in 1932 the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company, which offered life, health, and accident insurance to its customers. Gaston’s shrewd business acumen soon led him to add burial insurance, undertaking, casket manufacturing, and sales of burial plots in company-owned cemeteries to his list of services. In 1923, Gaston married Creola Smith and then founded Smith and Gaston Funeral Directors.

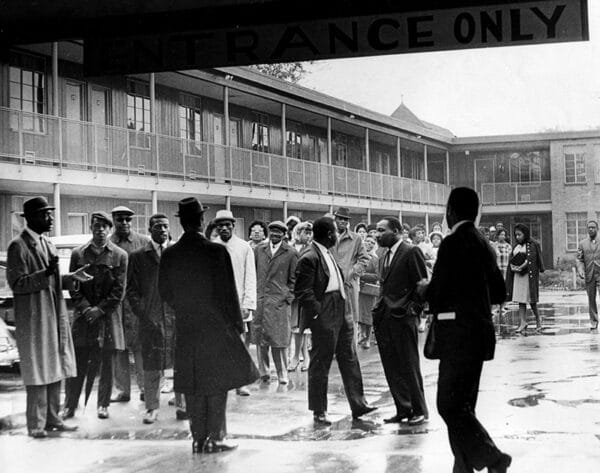

A. G. Gaston Motel

Gaston had a knack for seeing a business need and filling that niche. For example, in response to a noticeable shortage of qualified skilled clerks and typists in the day-to-day operations of his businesses, he founded the Booker T. Washington Business College in 1939. Gaston continued to fulfill needs and expand his empire by adding businesses, including the Vulcan Realty and Investment Company, the A. G. Gaston Home for Senior Citizens, the WENN-FM and WAGG-AM radio stations, S & G Public Relations Company, and the A. G. Gaston Motel. In the early 1950s, in response to difficulties for blacks in obtaining loans from white banks, he opened the Citizens Federal Savings and Loan Association, the first black-owned financial institution in Birmingham since the closing of the Alabama Penny Savings Bank 40 years earlier. Also at this time, he attempted to manufacture, bottle, and sell a soda called the Joe Louis Punch, trying perhaps to fill a need that was not so compelling. Of the numerous business ventures founded by Gaston, this was the only one that met with failure.

A. G. Gaston Motel

Gaston had a knack for seeing a business need and filling that niche. For example, in response to a noticeable shortage of qualified skilled clerks and typists in the day-to-day operations of his businesses, he founded the Booker T. Washington Business College in 1939. Gaston continued to fulfill needs and expand his empire by adding businesses, including the Vulcan Realty and Investment Company, the A. G. Gaston Home for Senior Citizens, the WENN-FM and WAGG-AM radio stations, S & G Public Relations Company, and the A. G. Gaston Motel. In the early 1950s, in response to difficulties for blacks in obtaining loans from white banks, he opened the Citizens Federal Savings and Loan Association, the first black-owned financial institution in Birmingham since the closing of the Alabama Penny Savings Bank 40 years earlier. Also at this time, he attempted to manufacture, bottle, and sell a soda called the Joe Louis Punch, trying perhaps to fill a need that was not so compelling. Of the numerous business ventures founded by Gaston, this was the only one that met with failure.

Gaston was not an outspoken advocate for civil rights, instead working quietly for equal treatment for blacks throughout his adult life. As early as the 1920s, Gaston not only encouraged his customers to save money, he also urged them to register to vote. In the 1950s, Gaston succeeded in having the “whites only” signs removed from the water fountains in the First National Bank as a result of privately threatening to close his account with the bank. In 1956, he provided a job to Autherine Lucy that gave her the financial support to become the first black student to register at the University of Alabama. Despite these efforts, Gaston earned criticism from some quarters for his low-key activities in relation to civil rights. Opposing the more confrontational tactics of Fred Shuttlesworth and his Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, Gaston served on the Committee of 100, a biracial group of Birmingham businessmen dedicated to bringing about desegregation in the city through less public means. This group had some initial success when downtown merchants agreed to desegregate their stores in the fall of 1962. Despite criticisms, Gaston provided space at a reduced rate in his motel to protest leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy for planning for their demonstrations. Gaston also bailed King out of jail when he was arrested in the spring of 1963, during the Birmingham Campaign.

Gaston himself became the victim of violence as a result of his support for King and Abernathy when his motel was bombed on May 12, 1963. In September 1963, Gaston’s home was bombed, but no one was injured and the house suffered minimal damage. In 1976, Gaston was again the victim of violence when he was kidnapped by an intruder, beaten with a hammer, handcuffed, and driven around the city for hours before the assailant was apprehended by police; the incident was thought to be prompted more by his financial status rather than his race.

In 1968, Gaston published his autobiography, Green Power: The Successful Way of A. G. Gaston, motivated in large part by his desire to promote black entrepreneurship and to regain respect in the black community. The book was well received and earned Gaston an appearance on The Today Show.

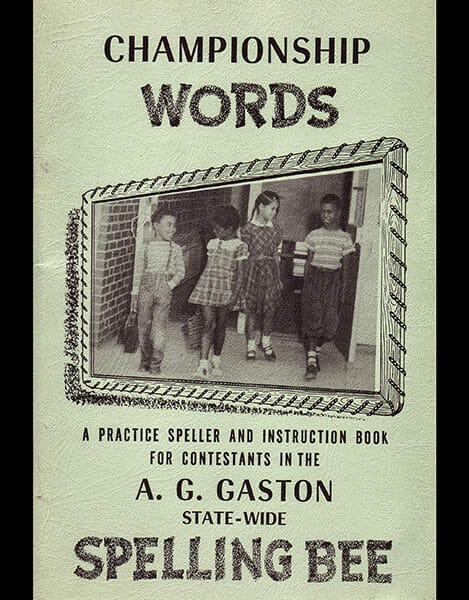

A. G. Gaston Spelling Bee

During the last decades of his life, Gaston amassed many honors and accolades. In 1975, he received an honorary law degree from Pepperdine University. In 1976, he was named an honorary president of Troy University and the Alabama Broadcasters Association named him its citizen of the year. Gaston was also honored by serving on the boards of trustees of Tuskegee University, Daniel Payne College, the Gorgas Scholarship Foundation, and the Eighteenth Street Branch YMCA. In 1992, he was named by the magazine Black Enterprise as “Entrepreneur of the Century.” Gaston gave back to the community in numerous ways, including donating $50,000 to establish the A. G. Gaston Boys Club in Birmingham and serving as its president. He also served on the boards of directors for the Jefferson County United Appeal, the Jefferson County Mental Health Association, the National Business League, Operation New Birmingham, and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

A. G. Gaston Spelling Bee

During the last decades of his life, Gaston amassed many honors and accolades. In 1975, he received an honorary law degree from Pepperdine University. In 1976, he was named an honorary president of Troy University and the Alabama Broadcasters Association named him its citizen of the year. Gaston was also honored by serving on the boards of trustees of Tuskegee University, Daniel Payne College, the Gorgas Scholarship Foundation, and the Eighteenth Street Branch YMCA. In 1992, he was named by the magazine Black Enterprise as “Entrepreneur of the Century.” Gaston gave back to the community in numerous ways, including donating $50,000 to establish the A. G. Gaston Boys Club in Birmingham and serving as its president. He also served on the boards of directors for the Jefferson County United Appeal, the Jefferson County Mental Health Association, the National Business League, Operation New Birmingham, and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

In 1986, Gaston added to his empire at the age of 94 with the A. G. Gaston Construction Company. The next year, Gaston rewarded his long-time employees by creating an employee stock option plan and sold the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company with assets totaling $34 million in assets to his employees for only $3.5 million. Gaston continued to operate the Citizens Federal Savings Bank and the Smith and Gaston Funeral Home in the 1990s despite suffering a stroke in 1992. Gaston, one of Alabama’s leading entrepreneurs, died on January 19, 1996, at the age of 103.

The Gaston Motel, an important gathering place in Birmingham for civil rights leaders and the scene of a bombing in 1963, was included as part of the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument created by Pres. Barack Obama in January 2017. In June 2023, the city of Birmingham completed a major renovation of the motel complex and opened it to the public for tours.

Further Reading

- Gaston, A. G. Green Power: The Successful Way of A. G. Gaston. 1968. Reprint, Troy, Ala.: Troy State University Press, 1977.

- Jenkins, Carol, and Elizabeth Gardner Hines. Black Titan, A. G. Gaston and the Making of a Black American Millionaire. New York: One World, 2004.

- Noles, James L. Hearts of Dixie: Fifty Alabamians and the State They Called Home. Birmingham, Ala.: Will Publishing, 2004.

- Smith, Suzanne E. To Serve the Living: Funeral Directors and the African American Way of Death. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010.