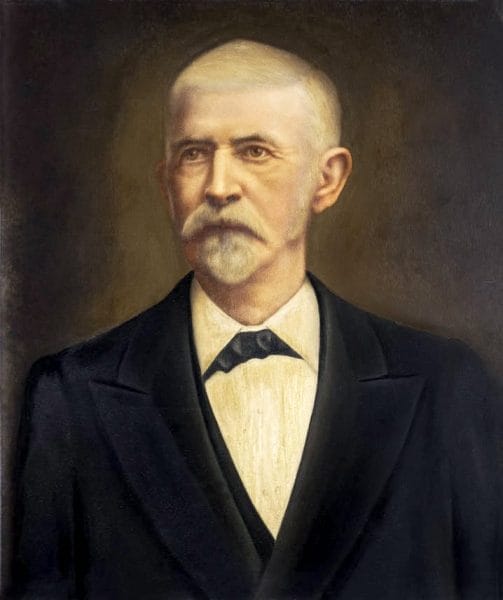

Emmet O'Neal (1911-15)

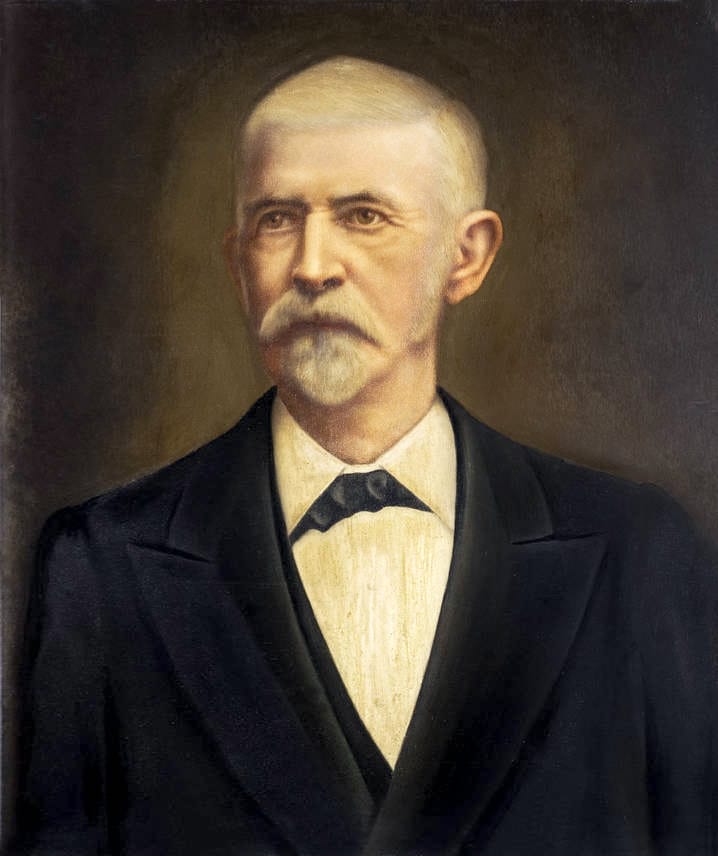

Emmet O’Neal

Like his father, Gov. Edward O’Neal, Emmet O’Neal (1853-1922) was president of the Alabama State Bar, framer of a state constitution, presidential elector, and governor of Alabama during the Progressive Era. O’Neal opposed voting rights for blacks and women as well as Prohibition, which he saw as an infringement of personal liberties, although he supported local control of the liquor trade. As governor, O’Neal presided over and fought to distance himself from a financial scandal, as did his father.

Emmet O’Neal

Like his father, Gov. Edward O’Neal, Emmet O’Neal (1853-1922) was president of the Alabama State Bar, framer of a state constitution, presidential elector, and governor of Alabama during the Progressive Era. O’Neal opposed voting rights for blacks and women as well as Prohibition, which he saw as an infringement of personal liberties, although he supported local control of the liquor trade. As governor, O’Neal presided over and fought to distance himself from a financial scandal, as did his father.

Born on September 23, 1853, in Florence, Lauderdale County, to Edward A. O’Neal and Olivia Moore O’Neal, Emmet attended Florence Wesleyan University (now the University of North Alabama, UNA) and the University of Mississippi before graduating in 1873 from the University of Alabama. In July 1881, he married Lizzie Kirkman in Tuscaloosa, and they had three children, two of whom survived him. Emmet studied and practiced law with his father until 1882, when he managed his father’s first campaign for governor. Two years later, he was on the campaign trail again, canvassing the state on behalf of his father’s reelection effort and running as presidential elector for Grover Cleveland. In 1892, O’Neal garnered his own political patronage for the first time when he was appointed U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Alabama, a position he held from 1893 to 1897, and he supported William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 presidential race. In 1900, O’Neil purchased Courtview, the mansion of Florence planter and industrialist George Washington Foster; it is now Rogers Hall on the UNA campus. He was serving as a Florence city alderman in 1901 when he was elected a delegate to the state’s constitutional convention.

At that convention, O’Neal served as chairman of the committee on local legislation and on the Committee on Suffrage and Elections, which effectively disfranchised blacks and poor whites and barred women voters from state elections. O’Neal publicly stated that the role of the convention was to solidify white supremacy in the state. He also spoke out against woman suffrage.

Five years later, while campaigning for lieutenant governor, O’Neal added a plank in his platform that supported white supremacy in voting rights and portrayed himself as a reform candidate. He advocated railroad rate regulation, liberal funding for education, and better highways. He denounced insurance companies and called for campaign finance reform and changes in the primary laws. At the same time, O’Neal favored conservative causes, including increased aid to Confederate veterans, local-option liquor laws, and immigration restrictions placed on persons of the “wrong sort,” including the poor, criminals, anarchists, the mentally ill, and especially Chinese people. O’Neal lost the election for lieutenant governor, but the contest afforded him statewide name recognition.

Despite that defeat, O’Neal remained active in politics and was elected president of the Alabama State Bar in 1909. During his two-year term, he led the opposition to ratification of a constitutional amendment that prohibited the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors in Alabama. The state was already dry effective January 1, 1909, through legislative statute, an act that O’Neal and others believed to be unconstitutional and a failure as well. O’Neal labeled the constitutional amendment an even worse encroachment on personal liberty, one that would put in danger the private actions of people within their own homes. On November 29, 1909, Alabamians agreed with O’Neal and rejected the amendment.

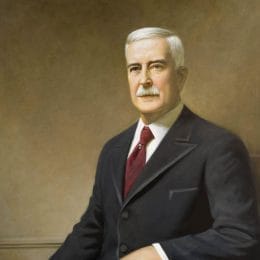

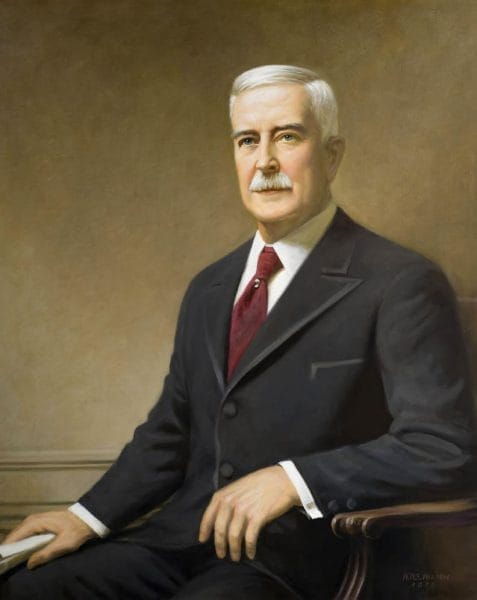

Braxton Bragg Comer

In January 1910, O’Neal announced his candidacy for governor. He attacked incumbent Braxton Bragg Comer‘s prohibition amendment, but pledged to enforce all laws, including the prohibition statute, until the people voted to revise, modify, or repeal them. O’Neal also provided voters with a rehash of the same platform of “reasonable” ideas he had offered in his race for lieutenant governor. He left no doubt, however, that the prohibition issue was foremost in his campaign. O’Neal easily won both the Democratic primary and the November general election races to become Alabama’s 36th governor. O’Neal believed the outcome of the election of 1910 reflected the voters’ protest against radical legislation and was a call for progressive conservatism. In his message to the legislature on January 16, 1911, the new governor raised every social, economic, and political problem confronting Alabama, but he devoted more than 25 pages of his speech to prohibition. In other matters, O’Neal recommended both fiscal restraint and increasing revenues to lower the state’s $1.5 million debt. He also addressed issues relating to local government, crime, transportation, and education reform, among many other issues.

Braxton Bragg Comer

In January 1910, O’Neal announced his candidacy for governor. He attacked incumbent Braxton Bragg Comer‘s prohibition amendment, but pledged to enforce all laws, including the prohibition statute, until the people voted to revise, modify, or repeal them. O’Neal also provided voters with a rehash of the same platform of “reasonable” ideas he had offered in his race for lieutenant governor. He left no doubt, however, that the prohibition issue was foremost in his campaign. O’Neal easily won both the Democratic primary and the November general election races to become Alabama’s 36th governor. O’Neal believed the outcome of the election of 1910 reflected the voters’ protest against radical legislation and was a call for progressive conservatism. In his message to the legislature on January 16, 1911, the new governor raised every social, economic, and political problem confronting Alabama, but he devoted more than 25 pages of his speech to prohibition. In other matters, O’Neal recommended both fiscal restraint and increasing revenues to lower the state’s $1.5 million debt. He also addressed issues relating to local government, crime, transportation, and education reform, among many other issues.

Before the legislature adjourned, many of the governor’s initiatives had been enacted. Most notably, the legislature repealed the statewide prohibition act that was passed during the Comer administration and replaced it with a local-option law. Important changes were also made in election procedures. Corporate donations to candidates were limited, and candidates were required to file expense statements and were prohibited from serving drinks or food on election day within 100 yards of polling places. The legislature provided procedures whereby cities could replace the ward system of government with the more “progressive” commission government.

Banner Mine Tragedy

As the legislative session continued, on April 8, 1911, an explosion at the Banner Coal Mine in Birmingham killed 128 miners, 123 of whom were convict laborers. This accident underscored the governor’s call for improved mine safety measures and prison reform. Six days later, the legislature enacted a mine safety law and established a board of mediation and arbitration to handle labor-management controversies. The legislature also appropriated an additional $500,000 for Confederate pensions, purchased an official residence for the governor that O’Neal and his family were the first to occupy in 1912, and approved a $100,000 addition to the capitol building.

Banner Mine Tragedy

As the legislative session continued, on April 8, 1911, an explosion at the Banner Coal Mine in Birmingham killed 128 miners, 123 of whom were convict laborers. This accident underscored the governor’s call for improved mine safety measures and prison reform. Six days later, the legislature enacted a mine safety law and established a board of mediation and arbitration to handle labor-management controversies. The legislature also appropriated an additional $500,000 for Confederate pensions, purchased an official residence for the governor that O’Neal and his family were the first to occupy in 1912, and approved a $100,000 addition to the capitol building.

Not all of O’Neal’s policies were enacted, however. The legislature approved the creation of the Alabama Highway Commission but rejected a tax to fund public highway construction and drivers’ examinations and licensing. Child labor was not addressed, nor did O’Neal win his proposal to allow district school taxes. Legislators did establish a rural library system, adopt a standard course of study for white students, and create a central board of trustees for the state’s normal schools. Moreover, during O’Neal’s tenure as governor the state appropriated almost $9 million for public education, nearly $2 million more than during any previous administration.

As with previous and subsequent governors, O’Neal gained national attention for his controversial views on various issues. While attending the third annual Governors’ Conference, hosted by Gov. Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey in September 1911, O’Neal ridiculed initiative, referendum, and recall, a progressive reform that gave citizens the right to initiate legislation, vote on issues, and recall officials, thus forcing them to stand for immediate reelection. At the fourth Governors’ Conference in 1912, O’Neal offered a resolution supporting national legislation that would prohibit interracial marriage.

O’Neal’s racial sentiments became even more clear when he chose Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) as the recipient of an annual sum of $10,000 in federal funds rather than give some of the money to Tuskegee Institute and the Huntsville State Colored Normal School (now Alabama A&M University). He did so despite the recommendation that he divide the money from his own all-white committee. Yet, O’Neal stood firmly against mob violence against blacks. When asked to pardon a white man guilty of having killed a black man, O’Neal declined. He encouraged prosecution of those accused of committing lynchings and said there was no distinction between a murder committed by a mob or a single individual. Indeed, during his tenure lynching declined significantly.

O’Neal’s reputation for law and order was seriously damaged, however, in the second year of his term. When he attended Woodrow Wilson’s inaugural as president in March 1913, a scandal broke involving James C. Oakley, president of the Convict Board, and his chief clerk, Theophilus Lacy. The state received more than $1 million from convict leasing in 1913, and an audit revealed that at least $115,000 and possibly as much as $150,000 was missing. Lacy disappeared with $90,000 and was later arrested in 1914 and claimed that a portion of the money had been paid to O’Neal. The governor vehemently denied this charge, calling it politically motivated. Lacy later retracted his accusation and was convicted of embezzlement and grand larceny and was sentenced to 16 years in prison. Oakley was removed from office, arrested, charged with embezzlement of state funds, and tried twice but acquitted. O’Neal, although not guilty of theft, appeared guilty of mismanagement. His enemies used this scandal to discredit his administration, and he spent most of the remainder of his term conducting investigations, defending himself, and trying to explain the various acts of fraud and embezzlement. Allegations of misconduct continued after O’Neal left office. A legislative investigative committee suspected that money set aside for maintenance of the governor’s mansion had been squandered. There were additional charges of irregularities and mismanagement of funds in the attorney general‘s office, the Military Department, and the Department of Agriculture, where two men were later found guilty of embezzlement. Investigators conducted a thorough scrutiny of O’Neal’s personal finances and business affairs, but no formal charges were brought against him. O’Neal claimed there were political motives behind the accusations and was defended in a 1915 editorial in the Montgomery Advertiser as an honest man.

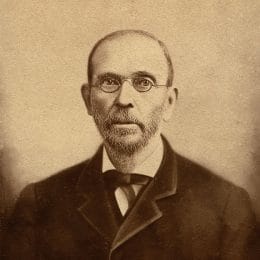

J. Thomas Heflin

After his tenure as governor, O’Neal was appointed a federal referee, with powers similar to those of a judge, in the bankruptcy court of Birmingham, earning considerably more than he had as governor. He interrupted his brief hiatus from politics in 1920 when he campaigned for the U.S. Senate on a platform of state sovereignty and “equal and exact justice to all men.” He spoke against the recently ratified Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote and which Alabama rejected. O’Neal lost the primary race to J. Thomas Heflin of Birmingham, who used the ex-governor’s 1914 pardon of a black man who had killed a white man to arouse voters against him.

J. Thomas Heflin

After his tenure as governor, O’Neal was appointed a federal referee, with powers similar to those of a judge, in the bankruptcy court of Birmingham, earning considerably more than he had as governor. He interrupted his brief hiatus from politics in 1920 when he campaigned for the U.S. Senate on a platform of state sovereignty and “equal and exact justice to all men.” He spoke against the recently ratified Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote and which Alabama rejected. O’Neal lost the primary race to J. Thomas Heflin of Birmingham, who used the ex-governor’s 1914 pardon of a black man who had killed a white man to arouse voters against him.

O’Neal died in Birmingham on September 7, 1922, and was buried in Florence. He never wore the progressive label but advocated a number of progressive measures. His fiscal policies and strong views on limited government at every level placed him squarely within the conservative faction of his party. On race, he was fairer than many of his contemporaries when dealing with racial tensions, but he was strictly a white supremacist in every other area.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Edwards, Inez N. “Emmet O’Neal: Alabama Governor, 1911–1915.” Master’s thesis, Auburn University, 1956.

- Ellis, Mary L. “Tilting on the Piazza: Emmet O’Neal’s Encounter with Woodrow Wilson September 1911.” Alabama Review 39 (April 1986): 83-95.

- Jones, Allen W. “Political Reforms in the Progressive Era.” Alabama Review 21 (July 1968): 163–72.

- Sellers, James B. The Prohibition Movement in Alabama, 1702-1943. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1943.

- Ward, Robert D., and William W. Rogers. Convicts, Coal, and the Banner Mine Tragedy. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1987.