Port of Mobile

New Cranes at Alabama State Docks

Situated between the confluence of the Alabama and Tombigbee Rivers and the Gulf of Mexico, Mobile‘s port has historically served as a shipping center for much of Alabama’s commercial products, particularly cotton, timber, and coal. As Alabama’s only port city, Mobile reaped the benefits of the antebellum cotton boom. In the decades after the Civil War, Mobile struggled to diversify its exports and move away from the declining cotton markets while city officials lobbied for large-scale investments in the city’s port and harbor facilities. During the two world wars, Mobile’s port became a center of shipbuilding for the region. Since World War II, the port has expanded and diversified more than at any point in its 300-year history.

New Cranes at Alabama State Docks

Situated between the confluence of the Alabama and Tombigbee Rivers and the Gulf of Mexico, Mobile‘s port has historically served as a shipping center for much of Alabama’s commercial products, particularly cotton, timber, and coal. As Alabama’s only port city, Mobile reaped the benefits of the antebellum cotton boom. In the decades after the Civil War, Mobile struggled to diversify its exports and move away from the declining cotton markets while city officials lobbied for large-scale investments in the city’s port and harbor facilities. During the two world wars, Mobile’s port became a center of shipbuilding for the region. Since World War II, the port has expanded and diversified more than at any point in its 300-year history.

Early History

Forest Products at the Port of Mobile

Early explorers recognized the strategic importance of Mobile Bay, from which they could move deep into the interior of the New World while maintaining a direct water route back to their ocean-going vessels in the Gulf. In 1702, the Le Moyne brothers established a settlement called Mobile approximately 30 miles up the Mobile River from Dauphin Island, which was one of the barrier islands protecting Mobile Bay. In 1711, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the younger of the two brothers, relocated the settlement at its current location at the terminus of the Mobile River so that they could be closer to the deeper waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Throughout the colonial era, Mobile Bay had a relatively shallow channel that prevented large cargo vessels from docking in Mobile. Larger cargo and passenger ships were offloaded at Dauphin Island to smaller ships, often called lighters, and transported into Mobile. This trend continued through Mobile’s three colonial occupiers: the French, British, and Spanish. In the earliest years, colonists constructed a long wooden pier, called the King’s Wharf, at Mobile’s waterfront; it extended over the shallow waters and marshes in the bay into the Mobile River. Larger vessels could unload their cargo at the end of the pier, but most oceangoing vessels still had to unload their cargo on Dauphin Island.

Forest Products at the Port of Mobile

Early explorers recognized the strategic importance of Mobile Bay, from which they could move deep into the interior of the New World while maintaining a direct water route back to their ocean-going vessels in the Gulf. In 1702, the Le Moyne brothers established a settlement called Mobile approximately 30 miles up the Mobile River from Dauphin Island, which was one of the barrier islands protecting Mobile Bay. In 1711, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the younger of the two brothers, relocated the settlement at its current location at the terminus of the Mobile River so that they could be closer to the deeper waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Throughout the colonial era, Mobile Bay had a relatively shallow channel that prevented large cargo vessels from docking in Mobile. Larger cargo and passenger ships were offloaded at Dauphin Island to smaller ships, often called lighters, and transported into Mobile. This trend continued through Mobile’s three colonial occupiers: the French, British, and Spanish. In the earliest years, colonists constructed a long wooden pier, called the King’s Wharf, at Mobile’s waterfront; it extended over the shallow waters and marshes in the bay into the Mobile River. Larger vessels could unload their cargo at the end of the pier, but most oceangoing vessels still had to unload their cargo on Dauphin Island.

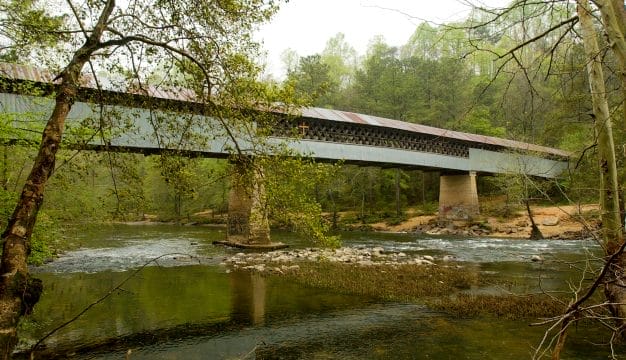

Tensaw River at Blakeley State Park

A more troublesome problem was shifting power relations and thus control of the extensive system of rivers that flowed into Mobile Bay by different European nations and Native American groups rather than by the city itself. These conditions severely limited access to the interior’s rich resources until the consolidation of the Mississippi Territory and the U.S. annexation of West Florida in the 1810s. When Mobile became part of the United States in 1813, the fledgling city’s port was finally connected with the river basin above it. New steam-powered vessels began to carry cotton and other commodities from the Black Belt downriver, and large storage warehouses and shipping companies soon covered the waterfront. The shallow waters of Mobile Bay, however, continued to hamper shipping. Even small draft vessels had difficulty navigating the waters and relied on local bar pilots to safely navigate their ships into Mobile. The shallow harbor around Mobile gave rise to a boomtown called Blakeley, located on the opposite side of the Tensaw River, which briefly posed a commercial threat to Mobile because of its deeper and more accessible port.

Tensaw River at Blakeley State Park

A more troublesome problem was shifting power relations and thus control of the extensive system of rivers that flowed into Mobile Bay by different European nations and Native American groups rather than by the city itself. These conditions severely limited access to the interior’s rich resources until the consolidation of the Mississippi Territory and the U.S. annexation of West Florida in the 1810s. When Mobile became part of the United States in 1813, the fledgling city’s port was finally connected with the river basin above it. New steam-powered vessels began to carry cotton and other commodities from the Black Belt downriver, and large storage warehouses and shipping companies soon covered the waterfront. The shallow waters of Mobile Bay, however, continued to hamper shipping. Even small draft vessels had difficulty navigating the waters and relied on local bar pilots to safely navigate their ships into Mobile. The shallow harbor around Mobile gave rise to a boomtown called Blakeley, located on the opposite side of the Tensaw River, which briefly posed a commercial threat to Mobile because of its deeper and more accessible port.

Business interests in Mobile, recognizing the limits that the shallow harbor placed on the city’s economic future, began to lobby the state for harbor improvements, and in 1824 the Alabama legislature established a commission to improve the harbor. The following year, citizens of Mobile successfully lobbied Alabama’s U.S. senator Rufus B. King to provide federal funds to deepen the ship channel by seven feet, which helped the port better accommodate larger ships. These harbor improvements helped Mobile become one of the largest ports in the South by the 1850s. In 1857, plans for another deepening of the ship channel were abandoned because of the looming Secession crisis.

Civil War

Soon after the Civil War began, the U.S. Navy instituted a blockade of Mobile Bay, and for the remainder of the war, economic activity at the port was severely limited. At the same time, Confederates built up their defenses at the entrance to Mobile Bay with well-armed batteries at Fort Morgan on Mobile Point and Fort Gaines on Dauphin Island while also littering the bay with mines (called torpedoes at the time).

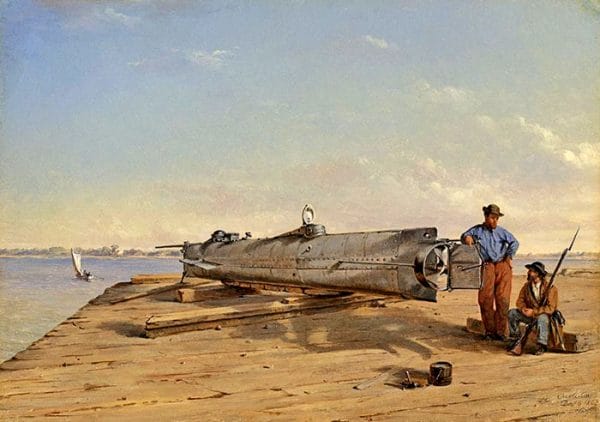

H. L. Hunley

Despite the blockade, blockade runners brought some supplies through. In 1862, when Union forces occupied New Orleans, entrepreneurial naval designer Horace L. Hunley destroyed his prototype submarine, named Pioneer, and relocated to Mobile to begin work on what would become the first submarine to sink an enemy ship, the H. L. Hunley. After the Battle of Mobile Bay in August 1864, the U.S. Navy took complete control of the port, and Navy mine sweepers then spent some eight months clearing Mobile Bay of the remaining mines placed by the Confederates. The interruption of supplies shipped in by blockade runners brought even worse economic conditions to the city. Finally, on April 12, 1865, the city’s mayor, Robert H. Slough, surrendered Mobile to advancing Union troops.

H. L. Hunley

Despite the blockade, blockade runners brought some supplies through. In 1862, when Union forces occupied New Orleans, entrepreneurial naval designer Horace L. Hunley destroyed his prototype submarine, named Pioneer, and relocated to Mobile to begin work on what would become the first submarine to sink an enemy ship, the H. L. Hunley. After the Battle of Mobile Bay in August 1864, the U.S. Navy took complete control of the port, and Navy mine sweepers then spent some eight months clearing Mobile Bay of the remaining mines placed by the Confederates. The interruption of supplies shipped in by blockade runners brought even worse economic conditions to the city. Finally, on April 12, 1865, the city’s mayor, Robert H. Slough, surrendered Mobile to advancing Union troops.

An even greater calamity occurred on May 25, 1865, when a warehouse containing 200 tons of ordnance exploded, killing 300 workers and devastating a large section of Mobile’s waterfront facilities. The cost and labor needed to rebuild a large portion of its port impeded the city’s postwar recovery.

Post-Civil War

In the early years after the war, annual cotton exports fell from a prewar average of 800,000 bales to less than 300,000. As a result, businessmen in Mobile began looking for new export opportunities. In 1868, they organized the Mobile Board of Trade and in 1869 launched a short-lived venture importing coffee from Latin America.

In 1870, the U.S. Congress approved a $50,000 project to clear wreckage from Mobile Bay and increase the depth of the ship channel to 13 feet, providing a much-needed boost to the shipping industry in Mobile. However, stiff competition from the expanding railroad system in the Black Belt threatened to bypass Mobile’s port altogether, favoring instead cities such as Montgomery and Selma. In the 1870s, Mobile leaders approved a $1.5 million bond issue to fund the Mobile and Alabama Grand Trunk Railroad, aimed at connecting Mobile to mineral-rich Birmingham. The project, however, ended in default after the financial panic of 1874.

By the end of the 1870s, Mobile stood on the brink of insolvency. In 1879, acting on the advice of Mobile businessmen, the Alabama legislature repealed Mobile’s charter and created a new government body called the “Port of Mobile.” Representatives for the Port of Mobile were charged with collecting back taxes, paying down Mobile’s debt, and managing the city using a fraction of its typical operating budget. In December 1886, the Alabama legislature reestablished the charter for the City of Mobile, and the final payment of the city’s debt was made in 1906.

By the late 1880s, a combination of federally financed harbor improvements, outside investments, and local boosterism drove a period of rapid expansion for the port. Members of the Mobile Chamber of Commerce, Cotton Exchange, and Commercial Club established the Mobile Joint Rivers and Harbors Committee, the purpose of which was to secure federal funds for maritime projects, including dredging Mobile Bay and improving the navigability of the rivers that flowed into Mobile Bay. The committee found allies in Alabama U.S. Senator Edmund Wilson Pettus and Congressman John Hollis Bankhead, who sat on the House Committee on Rivers and Harbors.

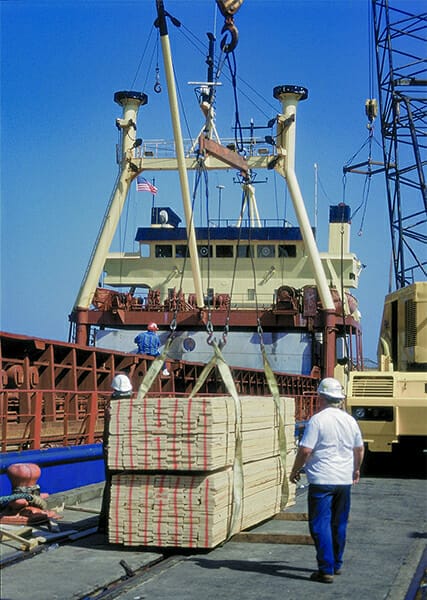

Cargo Ship Loading Forest Products at Port of Mobile

From 1880 to 1915, the federal government spent more than $7 million on improving Mobile’s harbor. Between 1880 and 1886, Maj. Andrew Damrell, a native of Massachusetts, oversaw an extensive dredging project by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that deepened the ship channel to 17 feet. By 1890, the channel reached a new depth of 23 feet, enabling, for the first time, deep-draft ocean-going vessels to dock at Mobile’s port. At the same time, expanded railroad access and federally funded improvements to river navigation made it easier to ship goods to the port. Also during this period, timber exports revived Mobile’s waterfront, with more than one billion feet of lumber shipped in 1889 alone. Other major export items included local seafood and oysters, and by 1893 Mobile also had become one of the largest importers of fruit from Latin America.

Cargo Ship Loading Forest Products at Port of Mobile

From 1880 to 1915, the federal government spent more than $7 million on improving Mobile’s harbor. Between 1880 and 1886, Maj. Andrew Damrell, a native of Massachusetts, oversaw an extensive dredging project by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that deepened the ship channel to 17 feet. By 1890, the channel reached a new depth of 23 feet, enabling, for the first time, deep-draft ocean-going vessels to dock at Mobile’s port. At the same time, expanded railroad access and federally funded improvements to river navigation made it easier to ship goods to the port. Also during this period, timber exports revived Mobile’s waterfront, with more than one billion feet of lumber shipped in 1889 alone. Other major export items included local seafood and oysters, and by 1893 Mobile also had become one of the largest importers of fruit from Latin America.

Twentieth Century and Beyond

America’s entry into World War I brought more changes to Mobile’s port. In 1917, the federal government created the Emergency Fleet Corporation to expand the nation’s small Merchant Navy force. The first shipbuilding contracts in Mobile were awarded in August 1917 to the Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company (ADDSCO). Because the ADDSCO facilities were inadequate for wartime production, the company had to first install heavy drydock equipment along the Mobile waterfront and build up its workforce. Consequently, only one vessel, the 3,500-ton freighter Banago, was completed during the war. Thereafter, approximately 50 ships were built in Mobile between 1918 and 1921.

Waterman Steamship

Concerned about the deficiencies of Mobile’s shipbuilding and ship repair industries, Mobile businessmen Walter Bellingrath, John Waterman, and C. W. Hempstead established in 1919 the Waterman Steamship Corporation, which became one of the largest shipping companies in the world. Its creation helped spur renewed interest in building up Mobile’s port facilities. In addition, local politicians lobbied the Alabama legislature to establish a state dock in the port city. In 1922, the legislature authorized construction of the Alabama State Docks and Gov. William Brandon appointed the first State Docks Commission. Retired general William L. Sibert, famed for his work on the Panama Canal, supervised construction of the state docks on a 500-acre site north of the city’s waterfront. The docks, which opened in 1928, more than doubled the city’s commercial shipping capacity.

Waterman Steamship

Concerned about the deficiencies of Mobile’s shipbuilding and ship repair industries, Mobile businessmen Walter Bellingrath, John Waterman, and C. W. Hempstead established in 1919 the Waterman Steamship Corporation, which became one of the largest shipping companies in the world. Its creation helped spur renewed interest in building up Mobile’s port facilities. In addition, local politicians lobbied the Alabama legislature to establish a state dock in the port city. In 1922, the legislature authorized construction of the Alabama State Docks and Gov. William Brandon appointed the first State Docks Commission. Retired general William L. Sibert, famed for his work on the Panama Canal, supervised construction of the state docks on a 500-acre site north of the city’s waterfront. The docks, which opened in 1928, more than doubled the city’s commercial shipping capacity.

World War II Ship Production

During World War II, wartime needs prompted unprecedented growth in the port facilities. ADDSCO increased its number of workers more than tenfold, and the nearby Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation installed new, larger drydocks. During the war, the city’s waterfront workforce increased to more than 89,000. Workers from throughout the state and region sought employment there, including Herbert and Stella Aaron, the parents of future baseball star Henry “Hank” Aaron, and country music pioneer Hank Williams. The demand for ships also opened new avenues of employment for African Americans and women. During the war, more than 200 ships were built in Mobile shipyards, but the end of the war brought a decline in activity along Mobile’s port. During the 1950s and 1960s, well-established companies such as ADDSCO and the Waterman Steamship Corporation curtailed their activities or merged with larger companies located elsewhere. In 1971, the Alabama legislature authorized the construction of a $16 million coal terminal on McDuffie Island in Mobile Bay, increasing the amount of coal that could be shipped quickly from Mobile. In 1975, the Alabama State Docks received a $45 million bond issue for internal improvements and expansion.

World War II Ship Production

During World War II, wartime needs prompted unprecedented growth in the port facilities. ADDSCO increased its number of workers more than tenfold, and the nearby Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation installed new, larger drydocks. During the war, the city’s waterfront workforce increased to more than 89,000. Workers from throughout the state and region sought employment there, including Herbert and Stella Aaron, the parents of future baseball star Henry “Hank” Aaron, and country music pioneer Hank Williams. The demand for ships also opened new avenues of employment for African Americans and women. During the war, more than 200 ships were built in Mobile shipyards, but the end of the war brought a decline in activity along Mobile’s port. During the 1950s and 1960s, well-established companies such as ADDSCO and the Waterman Steamship Corporation curtailed their activities or merged with larger companies located elsewhere. In 1971, the Alabama legislature authorized the construction of a $16 million coal terminal on McDuffie Island in Mobile Bay, increasing the amount of coal that could be shipped quickly from Mobile. In 1975, the Alabama State Docks received a $45 million bond issue for internal improvements and expansion.

The largest postwar investment in Mobile’s port came through the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway, a 234-mile long system of connecting rivers that provides access to the Gulf of Mexico at Mobile. President Richard Nixon traveled to Mobile in May 1971 to dedicate the project, which by the time it was completed in 1984 cost more than $2 billion. Today, timber and coal remain the chief exports shipped on the waterway.

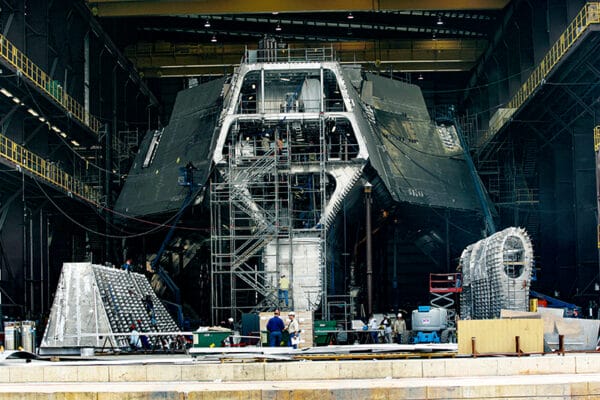

Austal Shipyard in Mobile

Shipping and shipbuilding remain of vital importance to Mobile’s port, which continues to attract new investments to the city as it expands. In 2010, the Alabama State Port Authority (Alabama State Docks) shipped more than 23 million tons of material from Mobile. AM/NS Calvert, a multinational steel corporation that owns a large refinery in north Mobile County, has a shipping terminal on Pinto Island. There is a coal terminal on McDuffie Island and a U.S. Coast Guard training facility on Little Sand Island. In recent years, Austal USA, one of the largest shipbuilders on the Gulf Coast, received a multi-billion dollar contract to build several littoral combat ships—high-speed, shallow draft warships—for the United States Navy. The first vessel completed in Mobile was the USS Independence (LCS 2), in 2009. Another large investment, the Choctaw Point Container Terminal, is currently under construction. Once completed, it will ship more than 75,000 containers annually. The Port of Mobile is the nation’s ninth largest port. Currently, its most frequent import and export commodities are coal, aluminum, iron, steel, lumber, wood pulp, and chemicals.

Austal Shipyard in Mobile

Shipping and shipbuilding remain of vital importance to Mobile’s port, which continues to attract new investments to the city as it expands. In 2010, the Alabama State Port Authority (Alabama State Docks) shipped more than 23 million tons of material from Mobile. AM/NS Calvert, a multinational steel corporation that owns a large refinery in north Mobile County, has a shipping terminal on Pinto Island. There is a coal terminal on McDuffie Island and a U.S. Coast Guard training facility on Little Sand Island. In recent years, Austal USA, one of the largest shipbuilders on the Gulf Coast, received a multi-billion dollar contract to build several littoral combat ships—high-speed, shallow draft warships—for the United States Navy. The first vessel completed in Mobile was the USS Independence (LCS 2), in 2009. Another large investment, the Choctaw Point Container Terminal, is currently under construction. Once completed, it will ship more than 75,000 containers annually. The Port of Mobile is the nation’s ninth largest port. Currently, its most frequent import and export commodities are coal, aluminum, iron, steel, lumber, wood pulp, and chemicals.

Further Reading

- Alsobrook, David E. “Alabama’s Port City: Mobile during the Progressive Era, 1896-1917,” (Ph.D. diss., Auburn University, 1983).

- Cronenberg, Allen. Forth to the Mighty Conflict: Alabama and World War II. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Friend, Jack. West Wind, Flood Tide: The Battle of Mobile Bay. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2004.

- McLaurin, Melton, and Michael V. R. Thomason. Mobile: The Life and Times of a Great Southern City. Woodland Hills, Calif.: Windsor Publications, 1981.

- O’Brian, Jack. “Where Was the Hunley Built?” Gulf South Historical Review 21 (Fall 2005): 29-56.

- Olliff, Martin T, ed. The Great War in the Heart of Dixie: Alabama during World War I. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

- Thomason, Michael V. R., ed. Mobile: The New History of Alabama’s First City. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.