Fort Apalachicola

During the seventeenth century, Spain, France, and Great Britain were competing over control over territory in what is now Alabama. An important component of that competition centered on trade with the Native American groups that lived there. As English colonists from Georgia and South Carolina began to trade more with the Indian groups, primarily of the Creek Nation, living along the Chattahoochee River, Spanish officials in Florida grew increasingly concerned that the Native Americans would begin to support the English over the Spanish. Fort Apalachicola was built by the Spanish in an attempt to thwart the trading practices of the English and to gain control of the southeastern United States.

Fort Apalachicola was a military and trade installation constructed in 1689 by the Spanish in what was then the colony of Florida. It was located in a big bend of the Chattahoochee River about 15 miles south of modern-day Phenix City, Russell County, on the west side of the Chattahoochee River. The site was chosen for its proximity to Apalachicola, the head town of the Lower Creek Indians during the middle of the eighteenth century. The installation was the northernmost of the Spanish forts that spread across northern Florida during the seventeenth century. The fort was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966 and stands as a modern symbol of the battle for control of the Southeast by European countries and as a symbol of the melding of cultures during the seventeenth century in the United States.

The fort was constructed by newly appointed governor of the Spanish colony of Florida, Don Diego De Quiroga y Losada. He acted without approval from the Spanish king because English traders had begun to settle and conduct business with local Native American groups immediately north of Spanish missions. The site was adjacent to the head town of Apalachicola, a Native American group linguistically related to the Creeks. Spain and England were competing for control over southeastern North America during the seventeenth century, and the English settlers’ activities immediately north of the Spanish stronghold in northern Florida were a threat to Spanish land claims.

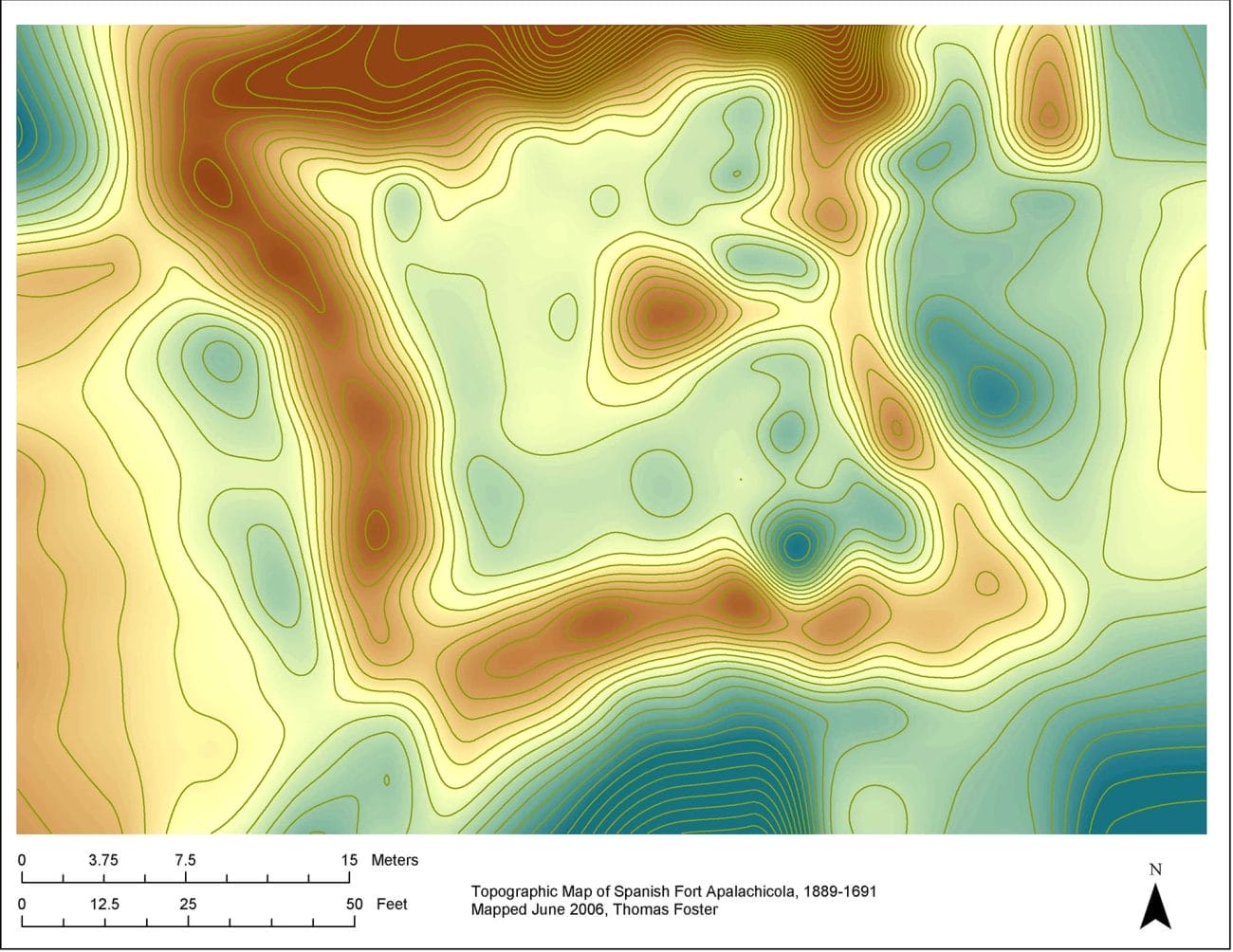

In 1689, the Florida governor sent 24 infantry, led by Captain Don Enrique Primo de Rivera, to oversee the construction. Much of the labor was performed by Indians from the Spanish mission villages in central Florida, including 100 Apalachee Indians, most of them carpenters. The structure was designed as a square blockhouse with bastions on each corner and surrounded by a stockade of sawn logs and a dry moat. The entire site measured approximately 72 feet (22 meters) across from the center of the moat on one side to the center of the moat on the other side.

Fort Apalachicola was completed in 1689. Twenty soldiers from Florida were stationed there. The fort was hastily built of sawn logs as a square palisaded structure with bastions at each corner and armed with canons for defense. The interior of the fort was laid out in rooms surrounding a central plaza. The structure was surrounded by a dry moat that is still visible today. By the following year, the attraction of English trade goods offered by South Carolina and Georgia settlers had coaxed the local Creek towns to move east of the Chattahoochee River. The Spanish king commanded that the fort be destroyed because he considered it too far from the settlements in Florida to defend. They dismantled the fort and removed all of the metal items, including nails and canons. In the aftermath of the Yamasee War of 1715-17 and in response to abuses by British traders, the Creeks moved back to the areas surrounding the fort.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the fort and surrounding town gradually were abandoned as the area’s Native American were forced from their homes through treaties and non-Indian squatters. The fort’s location faded from history until 1956, when it was rediscovered by Finbarr Ray, a Catholic monk living at the Holy Trinity monastery in Russell County. It was investigated soon after by Harold Huscher of the Smithsonian Institution and David Chase of the University of Alabama, who both were conducting research in the area.

Having been in private hands since its abandonment, ownership of the site of the fort was transferred to the Russell County Historic Commission for the price of one dollar in 1971. The outline of the fort has been protected by the moat and the surrounding terrain and is still relatively intact, and the moat is well defined, having not been filled in with dirt as were Spanish moats elsewhere around the Southeast. The site faces a number of preservation issues from erosion from the Chattahoochee River, which is steadily moving closer in its channel to the fort. Looting of historic artifacts is also a concern. The University of West Georgia is currently conducting archaeological research on the Native American village near the fort, and excavations have uncovered European trade goods and other artifacts relating to Native American life during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century. Some artifacts are located at the Columbus Museum in Columbus, Georgia, but the majority are housed at the Antonio J. Waring Jr. Archaeological Laboratory at the University of West Georgia. The artifacts collected during the University of Alabama excavation were given to Chattahoochee Valley Community College in Phenix City, but their location is currently unknown. Artifacts include beads, smoking pipes, gun parts, and broken vessels. The beads were commonly traded as personal adornment items by the Indian peoples in the area and are often found in such archaeological sites.

Further Reading

- Foster II, H. Thomas. Apalachicola: Resilience of a Native American Community on the Chattahoochee River. New York: Routledge, 2022.

- ———. “The Identification and Significance of Apalachicola for the Origins of the Creek Indians in the Southeastern United States.” Southeastern Archaeology 36 (June 2016): 1-13.

- ———. The Archaeology of the Lower Muskogee Indians, 1715-1836. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

- Hanberry, Brice B., et al. “Remembering Open Old Growth Forests of the Central Piedmont Province and the United States.” Écoscience 26 (July 2018): 1, 11-22.

- Harper, Francis, ed. The Travels of William Bartram. Naturalist’s Edition. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1998.

- Morrison, Kathleen D., et al. “Global-Scale Comparisons of Human Land-use: Developing Shared Terminology for Land-use Practices for Global Change.” Past Global Changes 26 (June 2018): 8-9.

- Pavao-Zuckerman, Barnet, et al. “Horned Cattle and Packhorses”: Zooarchaeological Remains from the Unauthorized (and Unscreened) Spanish Fort. Southeastern Archaeology 37 (April 2018): 190-203.

- Williams, Nancy K., and H. Thomas Foster II. “An Analysis of Interaction between Native Americans and Colonialists in the Southeastern United States.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 21 (June 2017): 513-531.