Confederate Memorial Park

Flag Display at Confederate Memorial Park Museum

In 1964, Confederate Memorial Park was established in Chilton County on the site of the state-run Confederate Soldiers’ Home, which operated from 1902 to 1939 as the state’s only care facility and residence for aging veterans of the Confederate Army, their wives, and widows. The park is home to the site of the original facility and other historic structures, as well as a museum, a research facility, and two Soldiers’ Home cemeteries. The park offers visitors tours and educational programming, a nature trail, and artifacts relating to the Civil War.

Flag Display at Confederate Memorial Park Museum

In 1964, Confederate Memorial Park was established in Chilton County on the site of the state-run Confederate Soldiers’ Home, which operated from 1902 to 1939 as the state’s only care facility and residence for aging veterans of the Confederate Army, their wives, and widows. The park is home to the site of the original facility and other historic structures, as well as a museum, a research facility, and two Soldiers’ Home cemeteries. The park offers visitors tours and educational programming, a nature trail, and artifacts relating to the Civil War.

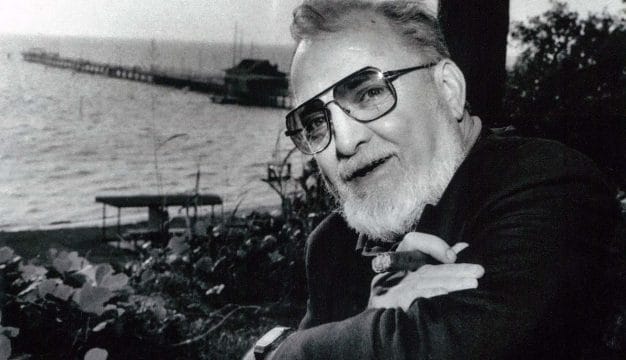

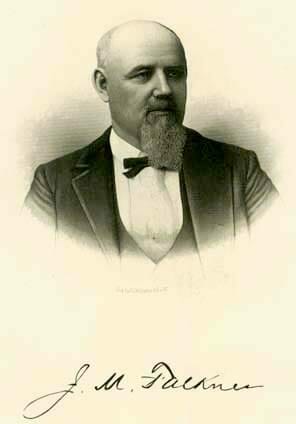

Jefferson Manly Falkner

By the 1890s, despite a depressed post-war southern economy and no federal funding for former Confederate soldiers, most southern states had established homes for indigent and disabled Confederate veterans. The driving force behind the establishment of a care facility for former soldiers in Alabama was former Confederate officer Jefferson Manly Falkner, an attorney and public official in Montgomery who had served in the 8th Confederate Cavalry. Falkner donated 102 acres of land near the lumber town of Mountain Creek in the southeast corner of Chilton County for the proposed home. Mountain Creek was considered an ideal site for such a facility because it had a reputation as a healthy area owing to its high elevation and numerous springs and running streams. It also had convenient access to rail lines.

Jefferson Manly Falkner

By the 1890s, despite a depressed post-war southern economy and no federal funding for former Confederate soldiers, most southern states had established homes for indigent and disabled Confederate veterans. The driving force behind the establishment of a care facility for former soldiers in Alabama was former Confederate officer Jefferson Manly Falkner, an attorney and public official in Montgomery who had served in the 8th Confederate Cavalry. Falkner donated 102 acres of land near the lumber town of Mountain Creek in the southeast corner of Chilton County for the proposed home. Mountain Creek was considered an ideal site for such a facility because it had a reputation as a healthy area owing to its high elevation and numerous springs and running streams. It also had convenient access to rail lines.

Home for Confederate Soldiers, 1902

Falkner organized public fund drives for a proposed United Confederate Veteran’s camp. Amounts and types of donations varied. For example, the Montgomery Weekly Advertiser reported in April 1902 that after one building committee member’s trip to Mobile, donations received included $125 in cash, $50 worth of “dressed lumber,” and 25,000 of the “best shingles.” Falkner organized a state-wide drive to sell tickets to hear former Tennessee governor Bob Taylor speak at the Montgomery auditorium on behalf of the Soldiers’ Home in May 1902; the effort raised nearly $4,000. Notable individuals also contributed, including Booker T. Washington and Eli Torrance, commander of the Union Army veterans organization. The large number of veterans applying to live at the home soon caused Falkner to ask for state assistance. In response, in October 1903, the State of Alabama assumed ownership and administration of the home. Falkner was appointed chairman of the executive committee of the Confederate Soldiers Home and served until his death in 1907.

Home for Confederate Soldiers, 1902

Falkner organized public fund drives for a proposed United Confederate Veteran’s camp. Amounts and types of donations varied. For example, the Montgomery Weekly Advertiser reported in April 1902 that after one building committee member’s trip to Mobile, donations received included $125 in cash, $50 worth of “dressed lumber,” and 25,000 of the “best shingles.” Falkner organized a state-wide drive to sell tickets to hear former Tennessee governor Bob Taylor speak at the Montgomery auditorium on behalf of the Soldiers’ Home in May 1902; the effort raised nearly $4,000. Notable individuals also contributed, including Booker T. Washington and Eli Torrance, commander of the Union Army veterans organization. The large number of veterans applying to live at the home soon caused Falkner to ask for state assistance. In response, in October 1903, the State of Alabama assumed ownership and administration of the home. Falkner was appointed chairman of the executive committee of the Confederate Soldiers Home and served until his death in 1907.

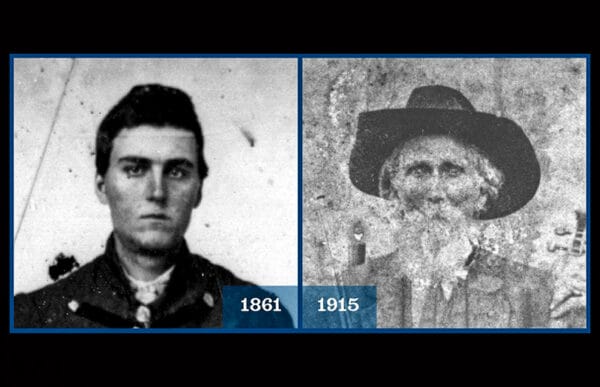

John S. Tucker

Construction of the facility began in April 1902, and in May the first veterans were admitted. Any Confederate veteran from any state was eligible to be admitted to the home if he had been a resident of Alabama for at least two years before application, served honorably (verified by Confederate records held by the U.S. War Department), and had a yearly income of less than $400 (which at that time was considered the poverty line). Wives were admitted with their veteran husbands if they had been married for at least five years and were more than 60 years of age. Wives of veterans who died at the home were supposed to leave, but records do not show any widows being made to leave; in 1915 this rule was changed to allow them to stay. Staff size at the home varied; in 1927 the staff consisted of the Commandant, a doctor and nurse, a dairyman, two laborers, three dishwashers, two cooks, and two washerwomen.

John S. Tucker

Construction of the facility began in April 1902, and in May the first veterans were admitted. Any Confederate veteran from any state was eligible to be admitted to the home if he had been a resident of Alabama for at least two years before application, served honorably (verified by Confederate records held by the U.S. War Department), and had a yearly income of less than $400 (which at that time was considered the poverty line). Wives were admitted with their veteran husbands if they had been married for at least five years and were more than 60 years of age. Wives of veterans who died at the home were supposed to leave, but records do not show any widows being made to leave; in 1915 this rule was changed to allow them to stay. Staff size at the home varied; in 1927 the staff consisted of the Commandant, a doctor and nurse, a dairyman, two laborers, three dishwashers, two cooks, and two washerwomen.

Memorial Hall

The Alabama Home for Confederate Soldiers consisted of 22 buildings, including 10 cottages, an administrative building, a hospital, a mess hall, and barns. The facility was intended to house a maximum of 100 residents. However, during its peak years (1914-1918), as many as 104 residents lived there. The last residing veteran died in June 1934. In October 1939, five remaining widows were transferred to the state welfare department in Montgomery, and the facility was officially closed. During its 37 years of operation, 650 to 800 veterans, wives, and widows resided at the home.

Memorial Hall

The Alabama Home for Confederate Soldiers consisted of 22 buildings, including 10 cottages, an administrative building, a hospital, a mess hall, and barns. The facility was intended to house a maximum of 100 residents. However, during its peak years (1914-1918), as many as 104 residents lived there. The last residing veteran died in June 1934. In October 1939, five remaining widows were transferred to the state welfare department in Montgomery, and the facility was officially closed. During its 37 years of operation, 650 to 800 veterans, wives, and widows resided at the home.

In 1964, during the Civil War centennial, an act of the Alabama State Legislature established the Confederate Memorial Park encompassing the original 102-acre site of the home as “a shrine to the honor of Alabama’s citizens of the Confederacy.” The Alabama divisions of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Alabama Sons of Confederate Veterans supported the bill sponsored by the Chilton County legislative delegation. The park was funded in perpetuity by a Confederate veterans and widows pension property tax millage, which had originally funded the Alabama Home for Confederate Soldiers when the state took control of the Home in October 1903. In 1971, the site was placed under the authority of the Alabama Historical Commission.

Confederate Memorial Park Museum

Currently, the site’s state-of-the-art museum, opened on April 28, 2007, interprets the life story of the average Alabama Confederate veteran from recruit to old age, incorporating hundreds of artifacts from the war and the home, six interactive media stations, and numerous interpretive panels. Driving and walking tours of the site include two cemeteries (where 298 veterans and 15 wives and widows are buried) and a nature trail through an official Alabama Treasure Forest, home to the second largest tulip poplar in Alabama.

Confederate Memorial Park Museum

Currently, the site’s state-of-the-art museum, opened on April 28, 2007, interprets the life story of the average Alabama Confederate veteran from recruit to old age, incorporating hundreds of artifacts from the war and the home, six interactive media stations, and numerous interpretive panels. Driving and walking tours of the site include two cemeteries (where 298 veterans and 15 wives and widows are buried) and a nature trail through an official Alabama Treasure Forest, home to the second largest tulip poplar in Alabama.

The site also houses the historic Mountain Creek Post Office, built around 1900, and the Marbury Methodist Church, built around 1885 (both of which were moved to the park from their original locations); and a Confederate Reference Library, opened in August 2008. Two large covered pavilions and several outdoor tables and grills are also available to the public.

Further Reading

- Hoar, Jay S. The South’s Last Boys in Gray. Bowling Green, Ky.: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1986.

- Rosenburg, R. B. Living Monuments, Confederate Soldiers’ Homes in the New South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

- Vandiver, Frank E. Their Tattered Flags, The Epic of the Confederacy. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1995.