Creek Indian Removal

The Creek Nation was once one of the largest and most powerful Indian groups in the Southeast. At their peak, the Creeks controlled millions of acres of land in the present-day states of Georgia, Alabama, and Florida. Much of this land, however, was lost or stolen as the federal government sought land for white settlement after the American Revolution. Creek lands were taken through cessions in treaties, through scams by land speculators, through outright theft by squatters, and also through clandestine arrangements between Creek headmen and federal agents. By 1836, most Creeks had relocated voluntarily or been forced to remove to Indian Territory, as the present-day state of Oklahoma was known at the time.

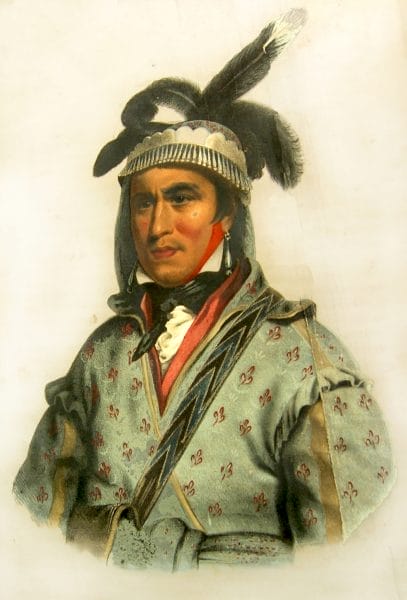

William McIntosh

On February 12, 1825, Coweta headman William McIntosh signed the Treaty of Indian Springs, which ceded all the Lower Creek land in Georgia and a large tract in Alabama to the federal government. In return, McIntosh and his followers received $200,000 and land in present-day Oklahoma. Most Creeks were overwhelmingly opposed to the land cession, and the sale of land without the approval of the Creek National Council was punishable by death under Creek law. Thus, in May 1825 McIntosh was executed at one of his plantations on the Chattahoochee River.

William McIntosh

On February 12, 1825, Coweta headman William McIntosh signed the Treaty of Indian Springs, which ceded all the Lower Creek land in Georgia and a large tract in Alabama to the federal government. In return, McIntosh and his followers received $200,000 and land in present-day Oklahoma. Most Creeks were overwhelmingly opposed to the land cession, and the sale of land without the approval of the Creek National Council was punishable by death under Creek law. Thus, in May 1825 McIntosh was executed at one of his plantations on the Chattahoochee River.

A delegation of Creeks also travelled to Washington, D.C., to try to nullify the treaty. A federal investigation of the treaty arrangements revealed that McIntosh did not have the support of the National Council and that Creeks were deeply opposed to the terms. On January 24, 1826, the Treaty of Indian Springs was nullified, and Creek leaders signed the Treaty of Washington, marking the only time that a ratified treaty with an Indian nation was overturned. The Treaty of Washington restored Creek land within Alabama but allowed the state of Georgia to keep ceded Creek lands. The treaty affected only the Lower Creeks, whose towns were clustered along the Chattahoochee and Flint Rivers. The Upper Creeks, who were further west, near present-day Montgomery, did not lose any land.

Emigration to Oklahoma

In late 1827, 703 Creeks, including 86 slaves, began their emigration to Fort Gibson in present-day Oklahoma (near present-day Muscogee). These emigrants were primarily supporters of William McIntosh and most were from McIntosh’s town of Coweta or its satellite town of Thlakatchka, although a number of other Creek towns also were represented. The emigrants rendezvoused briefly at Harpersville, just southeast of present-day Birmingham, before moving north to Tuscumbia. There, a large group of women, children, and elderly men boarded keelboats for their trip on the Tennessee, Ohio, and Mississippi rivers to Memphis. The remaining men, along with a number of women and children, continued by land to Memphis, where the parties reunited. From there, the keelboats continued by water to Fort Gibson, as the other party travelled by land, despite heavy rainfall that made the roads muddy and slowed their progress considerably. In some instances, the wagons containing their possessions could not be ferried across the many swollen rivers and were left behind. By the time the land party arrived at Fort Gibson in February 1828, agents observed that the emigrants were utterly worn down from the journey.

More voluntary emigrations followed. Almost a year after the first McIntosh party left Alabama, a second party of about 400 McIntosh supporters and their slaves travelled approximately the same route to the west. In 1829, a larger party of about 1,200 Creeks emigrated to present-day Oklahoma. Some of these Creeks were supporters of McIntosh; others were Creeks who had previously resided on land that now belonged to Georgia. Still others felt threatened by white settlers who illegally squatted on their land. The party left Alabama from Fort Bainbridge and Line Creek in east-central Alabama in June 1829. Like the two previous emigrations, the 1829 party also took land and water routes. While on the Arkansas River, the steamboat Virginia ran aground, and many of the emigrants lost property in the river.

Suffering in the West

The last of the travelers arrived in the West in September 1829, in the midst of a cholera epidemic. Indeed, disease was so rampant that many people packed their belongings and returned to Alabama. Those who stayed suffered raids by Western Indians who invaded Creek settlements at night. A delegation of Chickasaw, who were exploring the west for possible emigration, observed that the Creek emigrants were “in a poor condition” and were “continually mourning for the land of their births.”

Back in Alabama, the remaining Creeks also were suffering. As a result of continual white encroachment on Creek land, a number of prominent chiefs travelled to Washington to negotiate an agreement that they hoped would salvage the Creek Nation. The Treaty of Cusseta, signed in March 1832, traded the Creeks’ sovereign claim to their land in exchange for legal title to their land. Parcels of 640 acres for chiefs and 320 acres for everyone else were issued to Creek families, who could then sell them or remain on them for as long as they wished. Despite the appeal of land reserves, the Treaty of Washington failed to accomplish almost all of the goals it set out to achieve. Whites continued to encroach on Creek land, and when Creeks tried to sell their reserves they often were cheated by unscrupulous land speculators.

Second Creek War

Amidst these troubles, two more voluntary emigrating parties left Alabama in 1834 and 1835. A majority of the Creeks denounced emigration, however, and refused to go west. But continued encroachment on Creek land and the land frauds associated with selling Creek reserves caused sporadic violence between Creeks and white settlers into the 1830s. These skirmishes finally erupted into war in the spring of 1836. The Second Creek War, as it came to be called, involved Creeks from the towns of Chehaw, Yuchi, and Hitchiti, among others, who attacked whites and looted and destroyed plantations in the present-day Alabama counties of Chambers, Macon, Pike, Lee, Russell, and Barbour.

Opothle Yoholo

The violence provided Pres. Andrew Jackson with justification for removing all the Creeks from Alabama. After capturing the Creeks who participated in the uprising, soldiers chained and marched the prisoners to Montgomery, followed in wagons by related women and children. At Montgomery, the prisoners and their families were placed on steamboats and taken by ship to Mobile and New Orleans, before being marched through Arkansas to Fort Gibson. The remaining “friendly” Creeks were rounded up into five large detachments and marched west in August and September 1836. Because of his status as perhaps the most prominent Creek Indian, the government assigned leader Opothle Yoholo to lead the initial party. As they moved west, the emigrants experienced drought, torrential rains, and extreme cold and suffered from hypothermia as they arrived at their new homes in the West.

Opothle Yoholo

The violence provided Pres. Andrew Jackson with justification for removing all the Creeks from Alabama. After capturing the Creeks who participated in the uprising, soldiers chained and marched the prisoners to Montgomery, followed in wagons by related women and children. At Montgomery, the prisoners and their families were placed on steamboats and taken by ship to Mobile and New Orleans, before being marched through Arkansas to Fort Gibson. The remaining “friendly” Creeks were rounded up into five large detachments and marched west in August and September 1836. Because of his status as perhaps the most prominent Creek Indian, the government assigned leader Opothle Yoholo to lead the initial party. As they moved west, the emigrants experienced drought, torrential rains, and extreme cold and suffered from hypothermia as they arrived at their new homes in the West.

The Remaining Creeks

A sixth detachment, consisting of relatives of the warriors who had remained behind to fight alongside federal troops against the Seminoles, were told that they would be allowed to remain in east-central Alabama until the warriors’ tours of duty were over. But whites harassed the Creeks as they waited in camp, and the government moved them to Mobile Point. While there, the Creeks were plagued with sickness, and many died. The government then decided to move them to Pass Christian, Mississippi, which was considered healthier. In October 1837, after the warriors returned from Florida, the entire group departed Pass Christian for New Orleans, where they boarded steamboats for the trip up the Mississippi River. During the journey, the steamboat Monmouth was cut in two by another steamboat as it ascended the Mississippi, and approximately half of the 600 Creeks aboard died in the collision.

As these events took place, the government attempted to round up the remaining Creeks who had sought refuge among the Cherokees and Chickasaws. Almost 500 Creeks found among the Cherokees were marched to Gunter’s Landing (present-day Guntersville) and taken by boat to the West. Three hundred others who had escaped to Chickasaw lands travelled west in the wake of 1,000 emigrating Chickasaws.

Although Creeks continued to emigrate from Alabama in small, family-sized detachments into the 1840s and 1850s, government-sponsored removal ended officially in 1837 and 1838. Between the McIntosh party emigration in 1827 and the end of removal in 1837, more than 23,000 Creeks emigrated from the Southeast. Today, the Poarch Creek of Atmore, Escambia County, reside on the only remaining officially recognized Creek lands in the state.

Further Reading

- Foreman, Grant. Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1932.

- Green, Michael D. The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

- Haveman, Christopher D. “With Great Difficulty and Labour: The Emigration of the McIntosh Party of Creek Indians, 1827-1828.” Chronicles of Oklahoma 85 (Winter 2007-08): 468-90.

- ———. “Final Resistance: Creek Removal from the Alabama Homeland.” Alabama Heritage 89 (Summer 2008): 9-19.