Talladega Superspeedway

Talladega Superspeedway

Talladega Superspeedway, located in east-central Alabama, is the largest race track in the National Association for Stock Car Racing (NASCAR) and typically produces the fastest race speeds in the NASCAR circuit. The track is 2.66 miles in length, making it slightly longer than the 2.5-mile tracks at Daytona International Speedway and Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The track currently is home to two of NASCAR’s top-tier Sprint Cup Series races each year (the Aaron’s 499 and the Amp Energy 500), as well as annual races in the lower-level Nationwide Series, Truck Series, and ARCA Series. The grandstand has a seating capacity of 143,231, but actual attendance for the Sprint Cup races usually ranges anywhere from 150,000 to 170,000 because fans also are allowed to watch from the track’s infield.

Talladega Superspeedway

Talladega Superspeedway, located in east-central Alabama, is the largest race track in the National Association for Stock Car Racing (NASCAR) and typically produces the fastest race speeds in the NASCAR circuit. The track is 2.66 miles in length, making it slightly longer than the 2.5-mile tracks at Daytona International Speedway and Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The track currently is home to two of NASCAR’s top-tier Sprint Cup Series races each year (the Aaron’s 499 and the Amp Energy 500), as well as annual races in the lower-level Nationwide Series, Truck Series, and ARCA Series. The grandstand has a seating capacity of 143,231, but actual attendance for the Sprint Cup races usually ranges anywhere from 150,000 to 170,000 because fans also are allowed to watch from the track’s infield.

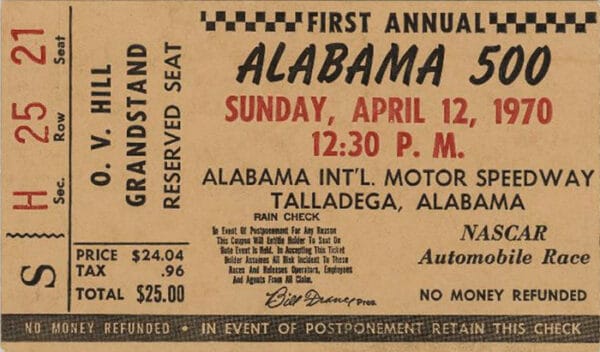

Alabama 500 Ticket

NASCAR founder Bill France Sr. helped create the track in the late 1960s. At the time, most major NASCAR facilities were located along the Atlantic Coast. France wanted a track that was more centrally located within the Southeast. He chose a 2,000-acre site just off Interstate 20, approximately 40 miles east of Birmingham near the town of Talladega, on an abandoned airfield. France envisioned a track that was longer, wider, and had greater banking in the turns than Daytona International Speedway, which had been designed to be the fastest track in NASCAR. The banking in the turns at Talladega is 33 degrees, compared with 31 degrees at Daytona. The backstretch straightaway is 4,000 feet long. The 4,300-foot, curving frontstretch creates a slight fifth turn in front of the main grandstand, which is why the track is called a trioval.

Alabama 500 Ticket

NASCAR founder Bill France Sr. helped create the track in the late 1960s. At the time, most major NASCAR facilities were located along the Atlantic Coast. France wanted a track that was more centrally located within the Southeast. He chose a 2,000-acre site just off Interstate 20, approximately 40 miles east of Birmingham near the town of Talladega, on an abandoned airfield. France envisioned a track that was longer, wider, and had greater banking in the turns than Daytona International Speedway, which had been designed to be the fastest track in NASCAR. The banking in the turns at Talladega is 33 degrees, compared with 31 degrees at Daytona. The backstretch straightaway is 4,000 feet long. The 4,300-foot, curving frontstretch creates a slight fifth turn in front of the main grandstand, which is why the track is called a trioval.

Alabama International Motor Speedway

Track construction began on May 23, 1968. The facility opened the following year as the Alabama International Motor Speedway and adopted the name Talladega Superspeedway in 1989. The track’s first race, the Bama 400, was held on September 13, 1969, in NASCAR’s second-tier Grand Touring circuit, with Ken Rush winning the event. The first Grand National race, called the Talladega 500, was held the next day. Richard Brickhouse won, taking the checkered flag seven seconds ahead of runner-up Jim Vandiver.

Alabama International Motor Speedway

Track construction began on May 23, 1968. The facility opened the following year as the Alabama International Motor Speedway and adopted the name Talladega Superspeedway in 1989. The track’s first race, the Bama 400, was held on September 13, 1969, in NASCAR’s second-tier Grand Touring circuit, with Ken Rush winning the event. The first Grand National race, called the Talladega 500, was held the next day. Richard Brickhouse won, taking the checkered flag seven seconds ahead of runner-up Jim Vandiver.

The inaugural race almost did not happen at all because many of NASCAR’s top drivers did not participate. Observing that cars were reaching nearly 200 miles per hour in practice and qualifying, drivers were concerned that the tires would not be able to handle such speed for an entire 500-mile race. These concerns prompted the Professional Drivers Association, led by Richard Petty, to call for a boycott of the race. Rather than cancel the race at the last minute, France decided to proceed with the drivers who did not participate in the boycott. The full 500 miles were completed without a major incident in front of a crowd estimated at 62,000.

Talladega Superspeedway Groundbreaking

The track quickly became accepted by drivers and fans alike. Two NASCAR race weekends were scheduled in 1970, and the track has since held twice-a-year events hosted by NASCAR. The first Talladega race of 1970, the Alabama 500, also was the first stock-car race nationally televised live under a new agreement between NASCAR and the America Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). In 1971, that same race was sponsored by R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company and was renamed the Winston 500. The sponsorship enabled Talladega to offer a total of $100,000 in prize money, which at the time was the largest in NASCAR’s history. In addition, NASCAR’s premier series became known as Winston Cup racing. Brothers Donnie and Bobby Allison, natives of the Birmingham suburb of Hueytown and part of what became known as NASCAR’s “Alabama Gang,” finished first and second in the inaugural Winston 500. The 46 lead changes in the race made it one of greatest in NASCAR history to that point. The track’s second race each year continued to be known as the Talladega 500 before picking up its first corporate sponsor, Sears DieHard batteries, in 1988.

Talladega Superspeedway Groundbreaking

The track quickly became accepted by drivers and fans alike. Two NASCAR race weekends were scheduled in 1970, and the track has since held twice-a-year events hosted by NASCAR. The first Talladega race of 1970, the Alabama 500, also was the first stock-car race nationally televised live under a new agreement between NASCAR and the America Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). In 1971, that same race was sponsored by R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company and was renamed the Winston 500. The sponsorship enabled Talladega to offer a total of $100,000 in prize money, which at the time was the largest in NASCAR’s history. In addition, NASCAR’s premier series became known as Winston Cup racing. Brothers Donnie and Bobby Allison, natives of the Birmingham suburb of Hueytown and part of what became known as NASCAR’s “Alabama Gang,” finished first and second in the inaugural Winston 500. The 46 lead changes in the race made it one of greatest in NASCAR history to that point. The track’s second race each year continued to be known as the Talladega 500 before picking up its first corporate sponsor, Sears DieHard batteries, in 1988.

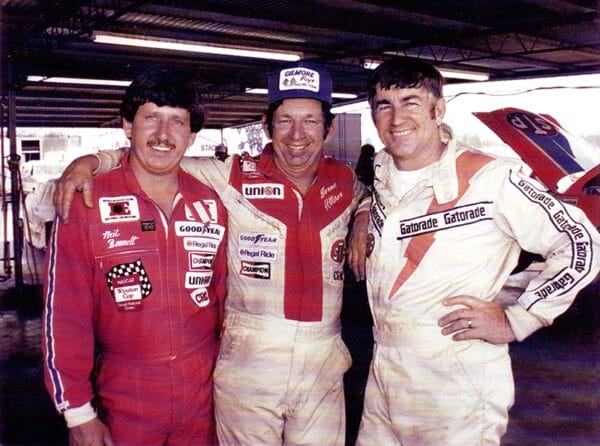

Neil Bonnett, Bobby Allison, and Donnie Allison

Races at Talladega continued to become faster and have closer finishes throughout the 1970s and 1980s, and consequently became more dangerous. The track’s first racing fatality occurred at the 1973 Talladega 500 when Larry Smith, the 1972 Winston Cup Rookie of the Year, died after his car hit the outside concrete wall in the first turn on the 14th lap. The only other death at the track during a NASCAR-sanctioned race occurred in the 1975 Talladega 500. Dwayne “Tiny” Lund died when his car spun on the sixth lap and was hit in the driver’s side by Terry Link’s car. Four drivers in the Auto Racing Club of America series (ARCA) died at Talladega in races between 1982 and 1991.

Neil Bonnett, Bobby Allison, and Donnie Allison

Races at Talladega continued to become faster and have closer finishes throughout the 1970s and 1980s, and consequently became more dangerous. The track’s first racing fatality occurred at the 1973 Talladega 500 when Larry Smith, the 1972 Winston Cup Rookie of the Year, died after his car hit the outside concrete wall in the first turn on the 14th lap. The only other death at the track during a NASCAR-sanctioned race occurred in the 1975 Talladega 500. Dwayne “Tiny” Lund died when his car spun on the sixth lap and was hit in the driver’s side by Terry Link’s car. Four drivers in the Auto Racing Club of America series (ARCA) died at Talladega in races between 1982 and 1991.

Talladega’s reputation for producing some of the most exciting races in NASCAR was firmly established in the late 1970s, when the margin of victory for the winner began to be measured routinely in tenths of a second. The 1981 Talladega 500 produced one of the closest finishes in NASCAR history when Ron Bouchard, Darrell Waltrip, and Terry Labonte crossed the finish line together, with Bouchard outpacing Waltrip for the victory by about two feet. Talladega reached the peak of competitive racing in the 1984 Winston 500. The 75 lead changes in that race established a NASCAR record that still stood until 2010, when a race in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series at Talladega recorded 88 lead changes.

The track hosted another NASCAR milestone on April 29, 1982, when Benny Parsons became the first driver to exceed 200 mph in qualifying, clocking 200.176 mph. For several years after that, qualifying itself became a major event at Talladega as drivers attempted to break the speed record. Cale Yarborough reached 202.650 mph in 1983 and then topped that mark a year later with a run of 202.692. In 1985, Bill Elliott shattered the record with a qualifying speed of 209.398. He reached 212.229 in 1986 and 212.809 in 1987. All 43 cars in the field for the 1987 Winston 500 qualified at speeds of more than 200 mph, and there was talk of the cars eventually reaching 220 mph.

All of that changed on May 3, 1987, when Bobby Allison lost control of his car during a race when it blew a tire. The rear end of the car spun around and the car became airborne, slamming into the catch fence that separated the track from the grandstands. The impact wiped out a 35-yard section of the fence, but fortunately the car bounced back onto the track, and no major injuries occurred among the fans in the grandstands. Allison suffered only minor injuries as well. Still, the image of an out-of-control car careening through the crowd horrified NASCAR officials, and it was quickly decided that the ever-escalating speeds had to be reduced.

Talladega Superspeedway

When the circuit returned to the track later that year for the Talladega 500, the cars were equipped with smaller carburetors that reduced engine horsepower and speed. The top qualifying speed was 203.827, which was 9 mph slower than Elliott’s record-setter in May, the final time that NASCAR had a car top the 200-mph mark. In 1988, carburetor restrictor plates were introduced for the races at both Talladega and Daytona. Over the years, NASCAR tweaked the size of the holes in the plate to cut back on the amount of air reaching the engine, further reducing horsepower and speeds. By 2001, top speeds had dropped to as slow as 185 mph, though they have since increased to the 190-mph range.

Talladega Superspeedway

When the circuit returned to the track later that year for the Talladega 500, the cars were equipped with smaller carburetors that reduced engine horsepower and speed. The top qualifying speed was 203.827, which was 9 mph slower than Elliott’s record-setter in May, the final time that NASCAR had a car top the 200-mph mark. In 1988, carburetor restrictor plates were introduced for the races at both Talladega and Daytona. Over the years, NASCAR tweaked the size of the holes in the plate to cut back on the amount of air reaching the engine, further reducing horsepower and speeds. By 2001, top speeds had dropped to as slow as 185 mph, though they have since increased to the 190-mph range.

In addition to slowing the cars, the restrictor plates also forced all the competitors to drive at approximately the same speed. As a result, Talladega became known as a track that produced thrilling races in which 30 to 40 cars would be packed tightly together, circling the track two- and three-wide. Most of the drivers hated it because it became very difficult for them to avoid trouble whenever there was a crash. Because the cars raced in a tight pack, even the slightest contact between two cars could start a chain reaction that would take out 10 to 20 others. These spectacular multi-car accidents were dubbed “The Big One,” and for better or worse, they have become a staple of racing at Talladega. This style of racing was extremely popular with the fans, and crowd size has surged to more than 150,000 for most races.

One driver who mastered the art of restrictor-plate racing at Talladega was Dale Earnhardt Sr. In his 27 Winston Cup races at the track following Allison’s accident, Earnhardt finished in the top five 17 times, including eight victories. He finished his career with 10 victories at Talladega, the most in track history, and he is the only driver to sweep both Talladega races in the same year twice (in 1990 and 1999). After Earnhardt’s death in 2001, his son took over as the dominant driver at Talladega. Dale Earnhardt Jr. won five Winston Cup races at the track from October 2001 to October 2004, including a record four in a row. The only driver other than the Earnhardts who has more than four career Winston Cup victories at the track is Jeff Gordon, who won there six times between 1996 and 2007.

After the April 2006 race weekend at Talladega Superspeedway, work immediately began on repaving the massive track for the first time in 26 years. When the drivers returned to Talladega that October, they gave the new racing surface rave reviews after participating in a race in which there were 63 lead changes, the most in a NASCAR event since 1984.

Richard Petty and Gen. Norton Schwartz at the Superspeedway

While races take place at the track only two weeks a year, the facility is used year-round in a variety of ways. One program allows fans to ride and drive around the track. Automakers use the track to test cars for both speed and endurance. Television commercials have been filmed there, as was part of the racing movie Talladega Nights. Alabama State Troopers and other law enforcement personnel use the track to train recruits in high-speed pursuit and defensive-driving techniques. But Talladega Superspeedway was built specifically to produce the fastest, most-exciting racing in NASCAR. Forty years after its creation, the track is still doing exactly that.

Richard Petty and Gen. Norton Schwartz at the Superspeedway

While races take place at the track only two weeks a year, the facility is used year-round in a variety of ways. One program allows fans to ride and drive around the track. Automakers use the track to test cars for both speed and endurance. Television commercials have been filmed there, as was part of the racing movie Talladega Nights. Alabama State Troopers and other law enforcement personnel use the track to train recruits in high-speed pursuit and defensive-driving techniques. But Talladega Superspeedway was built specifically to produce the fastest, most-exciting racing in NASCAR. Forty years after its creation, the track is still doing exactly that.

Additional Resources

Clyde Bolton. 25 Years of Talladega Superspeedway: A Quarter-century of Racing at the World’s Greatest Speedway. Charlotte, N.C.: UMI Publications, 1994.