Sloss Furnaces

Sloss Furnaces, a Birmingham-based iron-manufacturing complex, was established in 1881. The furnace and its various owners played a large role in the economic development of Birmingham. The site was declared a National Historical Landmark in 1981, one of the few industrial sites to be so designated, and offers visitors a chance to experience Birmingham’s industrial history. It is now an educational museum and home to a community of metal-working artists.

Col. James Withers Sloss, a plantation owner and railroad developer from Athens, Limestone County, founded the Sloss Furnace Company in the midst of an industrial boom that grew from Birmingham’s unique proximity to large deposits of coal, iron ore, and limestone in or near the Jones Valley. Sloss built two blast furnaces that went into production in April 1882 and May 1883, respectively. The furnaces, which featured a modern heated air-blast system, were located at the confluence of the Louisville and Nashville (L&N) and Alabama Great Southern railroads on the east side of the city.

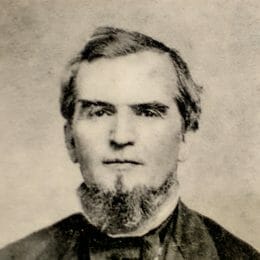

James W. Sloss

Although Sloss initially focused on the production of pig iron, he aspired to make steel, an iron-carbon alloy in high demand because it was easily shaped and resistant to abrasion, thus ideally suited for rails. Unfortunately, Birmingham’s raw materials were poorly suited for steel, and Sloss was unable to secure patent rights to any of the innovative processes that would overcome their limitations. Amid declining markets for pig iron, he sold control of his enterprise in the winter of 1886-87 to a group of investors, largely from Richmond, Virginia, that had greater access to funding. In the process, Sloss Furnace Company reorganized as the Sloss Iron and Steel Company (SISC), indicating the owners’ intention to pursue steel manufacture.

James W. Sloss

Although Sloss initially focused on the production of pig iron, he aspired to make steel, an iron-carbon alloy in high demand because it was easily shaped and resistant to abrasion, thus ideally suited for rails. Unfortunately, Birmingham’s raw materials were poorly suited for steel, and Sloss was unable to secure patent rights to any of the innovative processes that would overcome their limitations. Amid declining markets for pig iron, he sold control of his enterprise in the winter of 1886-87 to a group of investors, largely from Richmond, Virginia, that had greater access to funding. In the process, Sloss Furnace Company reorganized as the Sloss Iron and Steel Company (SISC), indicating the owners’ intention to pursue steel manufacture.

Joseph Bryan, a young attorney, led the Virginia syndicate and played a strong role in Birmingham’s development for more than two decades. The son of a wealthy tobacco planter, he was rooted in the upper classes of the antebellum plantation-agriculture system and had strong ties with northern bankers active in financing the shipment of southern agricultural commodities to Europe. Bryan and his fellow Virginians, mostly veterans of the Confederacy, were attracted to the postwar South because they believed that labor costs would be low, given the region’s large pool of African Americans seeking to escape the exploitation of sharecropping. This outlook permeated the future development of Sloss Furnaces. The Virginia industrialists also took advantage of the convict-lease system, which allowed them to lease prisoners at little cost to work in mines and other dangerous jobs. Sloss employed large numbers of convicts in its mines, including the Coalburg mine, which was known for its deplorable conditions and for its high death rate. In 1890, 90 of 1,000 prisoners died in the mines. Indeed, Sloss continued using convict labor after other large companies, including the Tennessee Iron, Coal and Steel Company (TCI), ended the practice. Bryan and his associates developed a satellite community, North Birmingham, where they built two additional blast furnaces and, in addition to Coalburg, established an increasing number of mining camps and company towns, including Blossburg, Brookside, and Cardiff, which was named for the predominantly Welsh immigrant workers who lived at the camp.

Bessie Mine Laborers

During this era, Bryan and his associates acquired brown-ore deposits near Leeds and integrated them into their growing industrial empire; Sloss researchers had discovered that the plentiful red ore in Jones Valley made a better grade of iron if combined with long-used brown ore. In competition with TCI, Birmingham’s largest enterprise, Bryan and SISC took control of blast furnaces, coal mines, and ore beds in Alabama’s northwest corner whose owners had gone under in the economic depression of the 1890s. The acquisitions resulted in a reorganized entity, the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company (SSSIC), indicating a continued interest in steel, a goal ardently desired by most of Birmingham’s businessmen. In 1899, TCI scored a coup by adopting complex new methods to produce the first significant output of steel ever in the Birmingham District at commercially competitive prices, leading boosters to dream that it would become the steelmaking capital of the world.

Bessie Mine Laborers

During this era, Bryan and his associates acquired brown-ore deposits near Leeds and integrated them into their growing industrial empire; Sloss researchers had discovered that the plentiful red ore in Jones Valley made a better grade of iron if combined with long-used brown ore. In competition with TCI, Birmingham’s largest enterprise, Bryan and SISC took control of blast furnaces, coal mines, and ore beds in Alabama’s northwest corner whose owners had gone under in the economic depression of the 1890s. The acquisitions resulted in a reorganized entity, the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company (SSSIC), indicating a continued interest in steel, a goal ardently desired by most of Birmingham’s businessmen. In 1899, TCI scored a coup by adopting complex new methods to produce the first significant output of steel ever in the Birmingham District at commercially competitive prices, leading boosters to dream that it would become the steelmaking capital of the world.

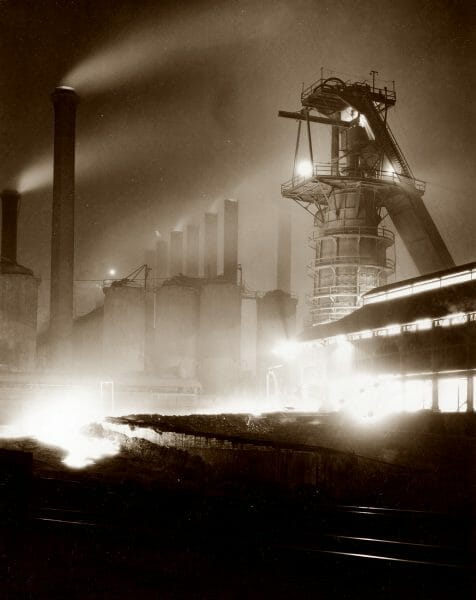

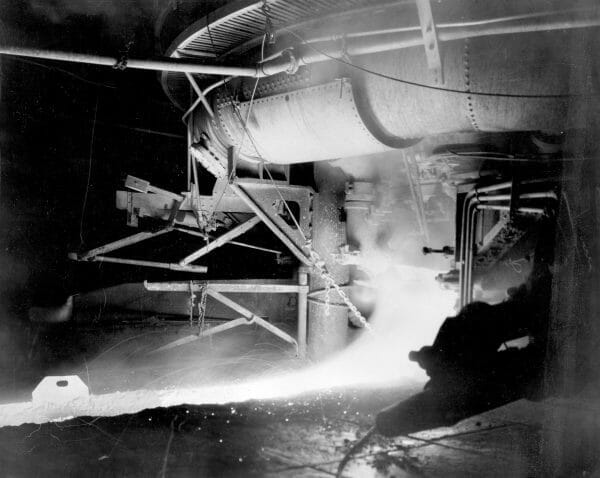

Molten Iron at Sloss Furnaces

Sloss-Sheffield was expected to follow TCI but did not. Bryan and his colleagues were cautious, using new technologies selectively. In 1895, they had rejected the adoption of an ingenious mechanical pig-iron casting system developed by engineer Edward A. Uehling, who then left SISC to work for steel magnate Andrew Carnegie in Pittsburgh. Bryan and his allies and supporters also overcame the objections of Edward O. Hopkins, an executive who wanted to embrace steelmaking. In 1902, Bryan’s forces decided to concentrate on producing high-quality pig iron for conversion into cast iron, a ferrous alloy for which Alabama iron ore was ideally suited because it contained a high level of phosphorus that promoted liquidity.

Molten Iron at Sloss Furnaces

Sloss-Sheffield was expected to follow TCI but did not. Bryan and his colleagues were cautious, using new technologies selectively. In 1895, they had rejected the adoption of an ingenious mechanical pig-iron casting system developed by engineer Edward A. Uehling, who then left SISC to work for steel magnate Andrew Carnegie in Pittsburgh. Bryan and his allies and supporters also overcame the objections of Edward O. Hopkins, an executive who wanted to embrace steelmaking. In 1902, Bryan’s forces decided to concentrate on producing high-quality pig iron for conversion into cast iron, a ferrous alloy for which Alabama iron ore was ideally suited because it contained a high level of phosphorus that promoted liquidity.

Cast iron could be readily molded into a large variety of intricate shapes, including engine valves, steam fittings, stove plates, automobile engine blocks, and piston rings, meeting the needs of the burgeoning automobile industry. Its resistance to corrosion also made it highly suitable for waste and sewer pipe, which carried liquids underground, and pressure pipe, which conveyed liquids in industrial applications. Although proponents of steel felt betrayed by Bryan, events proved that he had made a sound decision. Because of the special characteristics of southern iron, foundries from northern bastions like Pennsylvania moved steadily southward and to Alabama in particular. In time, it was said that there were two categories in the foundry trade: Alabama and the rest of the United States. Sloss-Sheffield and another local firm, the Woodward Iron Company, founded in Anniston, became America’s two main producers of foundry pig iron. Paradoxically, the Sloss Iron and Steel Company and the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company never made a single ounce of steel.

James W. McQueen

Before Bryan died in 1908, he selected his chief lieutenant, John C. Maben, to replace Hopkins, and Maben led SSSIC into a major period of expansion. During World War I, Maben delayed responding to government pressure to abandon antiquated “beehive” ovens, which allowed potentially valuable gases to escape during coke production, and he was forced out by new leaders, including Birmingham native James W. McQueen. As president, McQueen oversaw construction of massive by-product coke ovens that conserved gases for industrial use while also generating large quantities of electricity. Before McQueen died in 1925, he began modernizing Sloss-Sheffield’s blast furnaces by introducing slanting “skip hoists” that replaced vertical elevators carrying raw materials to the top of a stack and dumping them into “charging bells” that opened and closed to keep furnace gases from going to waste. Around this time, SSSIC was taken over by Allied Chemical and Dye Corporation, a New York-based company formed in 1920 and now known as Honeywell.

James W. McQueen

Before Bryan died in 1908, he selected his chief lieutenant, John C. Maben, to replace Hopkins, and Maben led SSSIC into a major period of expansion. During World War I, Maben delayed responding to government pressure to abandon antiquated “beehive” ovens, which allowed potentially valuable gases to escape during coke production, and he was forced out by new leaders, including Birmingham native James W. McQueen. As president, McQueen oversaw construction of massive by-product coke ovens that conserved gases for industrial use while also generating large quantities of electricity. Before McQueen died in 1925, he began modernizing Sloss-Sheffield’s blast furnaces by introducing slanting “skip hoists” that replaced vertical elevators carrying raw materials to the top of a stack and dumping them into “charging bells” that opened and closed to keep furnace gases from going to waste. Around this time, SSSIC was taken over by Allied Chemical and Dye Corporation, a New York-based company formed in 1920 and now known as Honeywell.

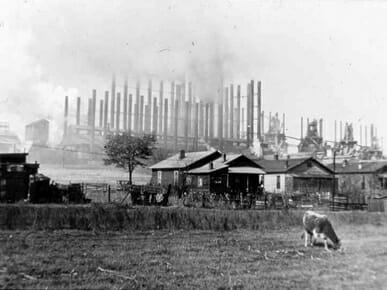

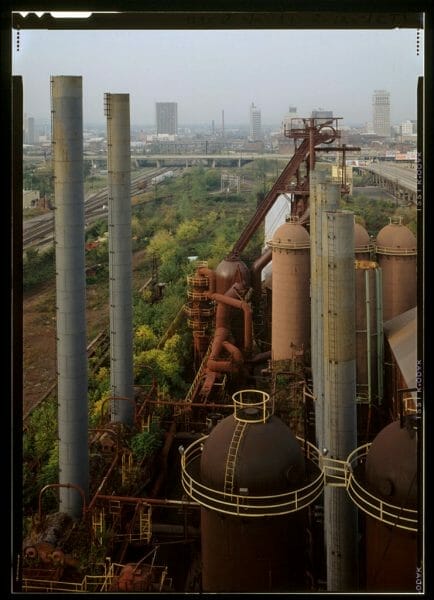

Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark

Hugh Morrow, a University of Alabama graduate, succeeded McQueen in 1925. Under Morrow and Allied Chemical and Dye, engineer James P. Dovel replaced the two original furnaces built by James W. Sloss in the 1880s with two completely new stacks that were adapted to southern raw materials and integrated them into an up-to-date layout in 1926. In 1942, Sloss-Sheffield became a subsidiary of the U.S. Pipe and Foundry Company, which built a huge new blast furnace in North Birmingham in 1958 that was designed to maximize scientific control over every aspect of making foundry pig iron. During the 1970s, increasing environmental regulations and energy shortages drove production prices to the breaking point, forcing the company to shutter its Alabama factories in 1980. The new blast furnace was torn down after being put out of operation, but the 1920 plant designed by Dovel was saved after a group of concerned citizens lobbied for its preservation. It was designated as Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark in September 1983, with the help of a grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark

Hugh Morrow, a University of Alabama graduate, succeeded McQueen in 1925. Under Morrow and Allied Chemical and Dye, engineer James P. Dovel replaced the two original furnaces built by James W. Sloss in the 1880s with two completely new stacks that were adapted to southern raw materials and integrated them into an up-to-date layout in 1926. In 1942, Sloss-Sheffield became a subsidiary of the U.S. Pipe and Foundry Company, which built a huge new blast furnace in North Birmingham in 1958 that was designed to maximize scientific control over every aspect of making foundry pig iron. During the 1970s, increasing environmental regulations and energy shortages drove production prices to the breaking point, forcing the company to shutter its Alabama factories in 1980. The new blast furnace was torn down after being put out of operation, but the 1920 plant designed by Dovel was saved after a group of concerned citizens lobbied for its preservation. It was designated as Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark in September 1983, with the help of a grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

In 2017, Sloss Furnaces was one of six Birmingham historical sites that organized to create the Birmingham Industrial Heritage Trail to celebrate the area’s significance in Alabama’s industrial and economic history.

Further Reading

- Committee for the Humanities in Alabama. Like It Ain’t Never Passed: Remembering Life in Sloss Quarters. Birmingham, Ala.: Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark, 1985.

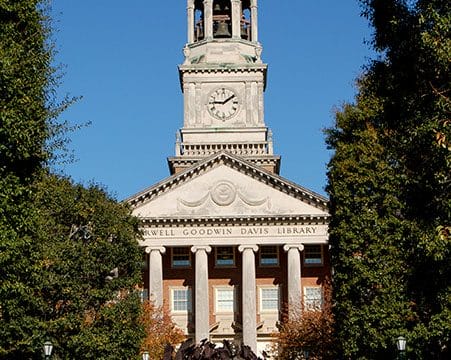

- Lewis, W. David. Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham District: An Industrial Epic. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.