Religion in Alabama

Alabama is a state in which 90 percent of its citizens profess belief in God and an overwhelming majority believe that the world was created in a single act some 10,000 years ago. Dominated by the Baptists in terms of sheer numbers, with Methodists a distant second, the state nevertheless runs the gamut of Christian denominations. In addition, non-Christian religions as well as agnostics and atheists likely also have had a presence in the state since its earliest years. As the population becomes more diverse and global, Alabama also finds itself opening up to new religions and belief systems.

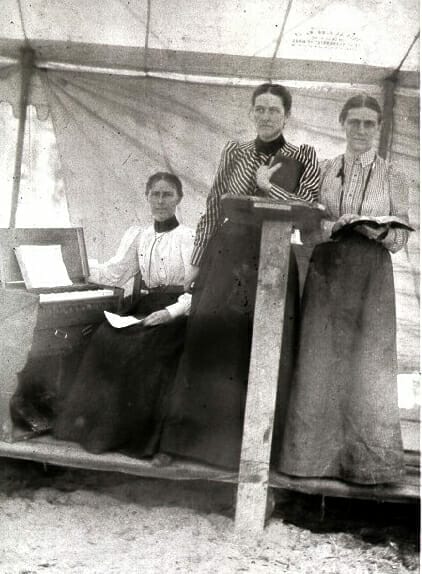

Mary Lee Cagle at a Tent Revival

By the late twentieth century, most Alabamians claimed to be religious and many national commentators viewed the state as the buckle of the Bible Belt, but it was not always so. Life on the early Alabama frontier was disorderly, chaotic, and (if early itinerant ministers can be believed) incredibly wicked. Widespread illiteracy and poverty accounted for the pervasive ignorance about religion in general and the Bible in particular. Churches were scattered, poorly organized, and normally met only seven or eight times a year (usually once a month except during the most severe winter months). Professions of faith in Jesus Christ generally occurred during highly emotional camp-meeting revivals, which usually took place in August or September during a lull in the agricultural cycle. For people trying to bring order to the dangerous and chaotic frontier, who experienced frightfully high rates of infant and maternal mortality, and who were totally dependent on the vagaries of nature for their livelihood, the hope of divine assistance and ultimate salvation and a home in heaven was, as the Bible promised, a “balm in Gilead.”

Mary Lee Cagle at a Tent Revival

By the late twentieth century, most Alabamians claimed to be religious and many national commentators viewed the state as the buckle of the Bible Belt, but it was not always so. Life on the early Alabama frontier was disorderly, chaotic, and (if early itinerant ministers can be believed) incredibly wicked. Widespread illiteracy and poverty accounted for the pervasive ignorance about religion in general and the Bible in particular. Churches were scattered, poorly organized, and normally met only seven or eight times a year (usually once a month except during the most severe winter months). Professions of faith in Jesus Christ generally occurred during highly emotional camp-meeting revivals, which usually took place in August or September during a lull in the agricultural cycle. For people trying to bring order to the dangerous and chaotic frontier, who experienced frightfully high rates of infant and maternal mortality, and who were totally dependent on the vagaries of nature for their livelihood, the hope of divine assistance and ultimate salvation and a home in heaven was, as the Bible promised, a “balm in Gilead.”

Formative Years

In Alabama’s early days, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists competed almost equally for adherents, as smaller numbers of Episcopalians, Jews, and Catholics exercised social, economic, and political influence beyond their numbers. Presbyterians, though numerous, were too centralized and required too high a level of education even to provide a reliable supply of pastors for their churches. Methodists, who established their first congregation in 1808, earned the early advantage in numbers of members because of their itinerant circuit riders, who spread out across the state, proclaiming a simple, emotional gospel of God’s unmerited grace that any sinner could freely claim.

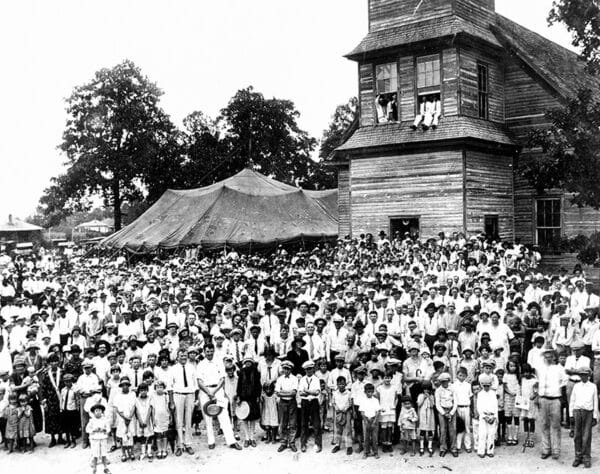

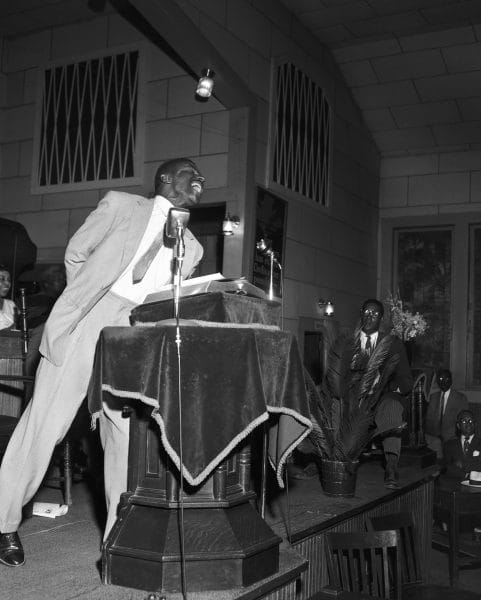

Revival at Fairmont Baptist Church

Baptists, who also established their first church in 1808 in Huntsville, suffered from internal disagreements about Calvinism, with some nearly as open to the prospect of free will (by which God predestined nothing and all who chose repentance could obtain salvation) as Methodists. Other Baptists were so democratic and hyper-Calvinist in their belief that God had settled everyone’s fate at the beginning of time that they organized as Primitive Baptists. They rejected mission and temperance societies, Sunday schools, salaried clergy and ministerial titles, any kind of organizational structure beyond the local congregation, and all forms of denominational education. The ease with which Baptist men accepted the call to preach and their typical bivocationalism (that is, they had to have a job outside of their ministry partly because many Baptist churches paid ministers either nothing at all or too little to cover their basic living expenses), meant that Baptist ministers were always much like their congregations in terms of social standing. And the absolute autonomy of every Baptist church reinforced the independence typical of the Alabama frontier. Churches might establish loose voluntary linkages through regional associations or even a state convention, but these associations exercised no authority over individual churches; even “messengers” elected from their churches to attend such meetings could act for no one except themselves. By the time of the Civil War, Baptists and Methodists each claimed slightly more than 60,000 adherents statewide.

Revival at Fairmont Baptist Church

Baptists, who also established their first church in 1808 in Huntsville, suffered from internal disagreements about Calvinism, with some nearly as open to the prospect of free will (by which God predestined nothing and all who chose repentance could obtain salvation) as Methodists. Other Baptists were so democratic and hyper-Calvinist in their belief that God had settled everyone’s fate at the beginning of time that they organized as Primitive Baptists. They rejected mission and temperance societies, Sunday schools, salaried clergy and ministerial titles, any kind of organizational structure beyond the local congregation, and all forms of denominational education. The ease with which Baptist men accepted the call to preach and their typical bivocationalism (that is, they had to have a job outside of their ministry partly because many Baptist churches paid ministers either nothing at all or too little to cover their basic living expenses), meant that Baptist ministers were always much like their congregations in terms of social standing. And the absolute autonomy of every Baptist church reinforced the independence typical of the Alabama frontier. Churches might establish loose voluntary linkages through regional associations or even a state convention, but these associations exercised no authority over individual churches; even “messengers” elected from their churches to attend such meetings could act for no one except themselves. By the time of the Civil War, Baptists and Methodists each claimed slightly more than 60,000 adherents statewide.

Divisions existed within Christian denominations over theology, gender, class, and race. Traditionalists accused modernizers of deserting the primitive Christian faith for faddish new doctrines. Women were not welcomed to the pulpit of any churches and in many sat on separate sides of the building from men. Nor could they vote in most church business meetings. Poor parishioners often felt unwelcome in affluent churches. And although slaves often dominated church membership rolls in Black Belt congregations, they usually were seated in restricted sections and were not allowed to serve as pastors or in other leadership roles. After the 1830s, state law also required that whites be present when black preachers spoke to their own people. Still, African Americans such as the Rev. Caesar Blackwell of Montgomery became so famous that even white congregations invited him to preach at revivals.

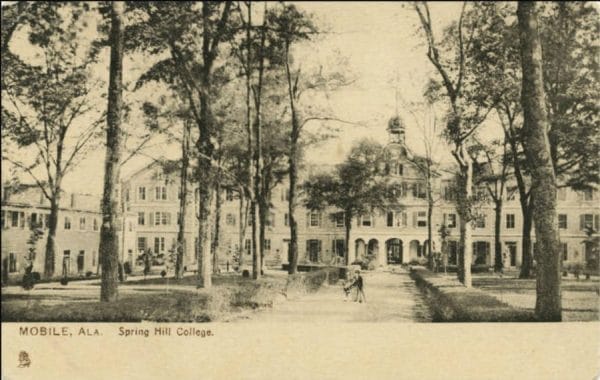

Spring Hill College, 1918

During the antebellum period, all the major denominations established schools and colleges to train ministers, priests, and laypeople. Mobile‘s Spring Hill College, founded in 1830, became the South’s earliest Jesuit college. Methodists organized colleges across the state, the most notable being Southern University (later, Birmingham-Southern College), which opened in Greensboro in 1859. In nearby Marion, also in the affluent Black Belt, Baptist planters (including planter-business woman Julia Tarrant Barron) founded Judson College for women in 1838 and Howard College for men in 1841.

Spring Hill College, 1918

During the antebellum period, all the major denominations established schools and colleges to train ministers, priests, and laypeople. Mobile‘s Spring Hill College, founded in 1830, became the South’s earliest Jesuit college. Methodists organized colleges across the state, the most notable being Southern University (later, Birmingham-Southern College), which opened in Greensboro in 1859. In nearby Marion, also in the affluent Black Belt, Baptist planters (including planter-business woman Julia Tarrant Barron) founded Judson College for women in 1838 and Howard College for men in 1841.

The Civil War ended or significantly impeded this progress. As sectional tensions grew in the decades before the Civil War, white evangelicals fiercely defended the institution of slavery and proclaimed its Biblical origins. In 1844, southern Methodists split from their national denomination, and the following year southern Baptists did likewise. The Christian Church divided in 1854 and the Presbyterians in 1861. By and large, white Christians also supported secession and proclaimed God’s blessings on the Confederacy.

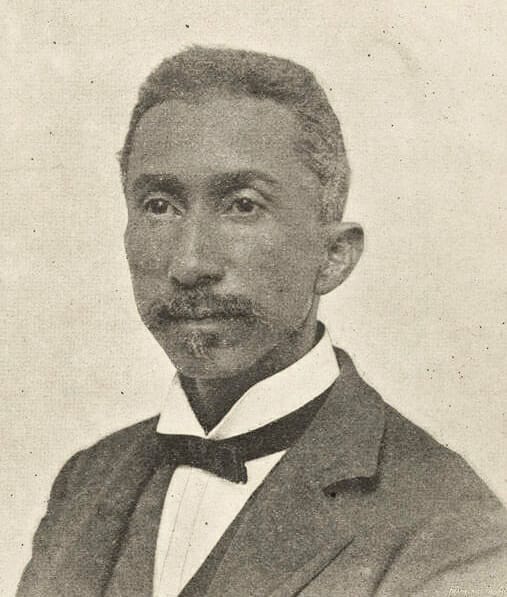

Charles Octavius Boothe

During the years immediately following the Civil War, black members withdrew from churches, sometimes amidst rancor from white church members, at other times with white approval and financial assistance. Prominent black Baptist pastors such as Charles O. Boothe and Nathan Ashby became significant national religious leaders—Boothe as founding pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church (later Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church) and historian of the black denomination, and Ashby as pastor of Montgomery’s Columbus Street Baptist Church. Ashby built his congregation into reputedly the nation’s largest black church, with 5,000 members. It was at his church that the National Baptist Convention, Inc., the nation’s largest black denomination, was organized, with Ashby elected as its first president. Not only did the nation’s largest black missionary Baptist denomination begin in Alabama, but also the anti-mission National Primitive Baptist Convention, organized in Huntsville in 1907 at the denomination’s main church, St. Bartley Primitive Baptist Church. Black pastors also served as social, business, educational, and political leaders within their communities.

Charles Octavius Boothe

During the years immediately following the Civil War, black members withdrew from churches, sometimes amidst rancor from white church members, at other times with white approval and financial assistance. Prominent black Baptist pastors such as Charles O. Boothe and Nathan Ashby became significant national religious leaders—Boothe as founding pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church (later Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church) and historian of the black denomination, and Ashby as pastor of Montgomery’s Columbus Street Baptist Church. Ashby built his congregation into reputedly the nation’s largest black church, with 5,000 members. It was at his church that the National Baptist Convention, Inc., the nation’s largest black denomination, was organized, with Ashby elected as its first president. Not only did the nation’s largest black missionary Baptist denomination begin in Alabama, but also the anti-mission National Primitive Baptist Convention, organized in Huntsville in 1907 at the denomination’s main church, St. Bartley Primitive Baptist Church. Black pastors also served as social, business, educational, and political leaders within their communities.

This tradition continued into the twentieth century with four of the nation’s premier civil rights leaders—Martin Luther King Jr., Fred Shuttlesworth, John Lewis, and Ralph D. Abernathy—who were all either Baptist native sons or pastored in the state. It is not too strong a statement that Alabama’s civil rights revolution largely began in black churches, which were able to mobilize their members into a mass movement.

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

Both proponents and opponents of racial change profited from oratorical skills expertly honed in evangelical churches. Liturgical churches, such as Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and some Episcopal congregations, followed carefully prescribed rituals for public worship. Evangelical churches were pulpit-centered; they were sermon-based and followed unstructured and often spontaneous patterns of worship and emphasized the Word (both the authority of the Bible and the proclamation of the Word in the form of a sermon). Years of proclamation often transformed uneducated black and white preachers into spell-binding orators with devoted followings, as influential over the politics of their congregants as they were over their theology.

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

Both proponents and opponents of racial change profited from oratorical skills expertly honed in evangelical churches. Liturgical churches, such as Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and some Episcopal congregations, followed carefully prescribed rituals for public worship. Evangelical churches were pulpit-centered; they were sermon-based and followed unstructured and often spontaneous patterns of worship and emphasized the Word (both the authority of the Bible and the proclamation of the Word in the form of a sermon). Years of proclamation often transformed uneducated black and white preachers into spell-binding orators with devoted followings, as influential over the politics of their congregants as they were over their theology.

Complexities and Divisions

Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception

As black and white churches set out on separate paths, the state also became more religiously complex. Groups such as the Churches of Christ and Cumberland Presbyterians had always found adherents in the Tennessee Valley and hill region, but immigrants attracted by the state’s rapid industrialization after 1880 brought new religious expressions. Eastern European Jews arrived, as did some Orthodox Christians from the same region. The arrival of Scottish coal miners increased the number of Presbyterians from 5,800 in 1880 to 12,000 by 1897. The Catholic population of Birmingham exploded as thousands of Italian miners and steel workers arrived. The 1906 U.S. religious census listed the church population of Birmingham as 29 percent Catholic, followed by black Baptists (15 percent), white Methodists (14 percent), and white Baptists in distant fifth place (7.5 percent). Nonetheless, in 1900 the state overall remained 97 percent Protestant, with Baptists and Methodists still closely bunched (46.2 percent and 43.4 percent of church membership, respectively). Roman Catholics, despite their significant presence in Mobile, Birmingham, and Cullman, represented only 2.4 percent of total church members (though that was more than either the Disciples of Christ or the Episcopalians).

Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception

As black and white churches set out on separate paths, the state also became more religiously complex. Groups such as the Churches of Christ and Cumberland Presbyterians had always found adherents in the Tennessee Valley and hill region, but immigrants attracted by the state’s rapid industrialization after 1880 brought new religious expressions. Eastern European Jews arrived, as did some Orthodox Christians from the same region. The arrival of Scottish coal miners increased the number of Presbyterians from 5,800 in 1880 to 12,000 by 1897. The Catholic population of Birmingham exploded as thousands of Italian miners and steel workers arrived. The 1906 U.S. religious census listed the church population of Birmingham as 29 percent Catholic, followed by black Baptists (15 percent), white Methodists (14 percent), and white Baptists in distant fifth place (7.5 percent). Nonetheless, in 1900 the state overall remained 97 percent Protestant, with Baptists and Methodists still closely bunched (46.2 percent and 43.4 percent of church membership, respectively). Roman Catholics, despite their significant presence in Mobile, Birmingham, and Cullman, represented only 2.4 percent of total church members (though that was more than either the Disciples of Christ or the Episcopalians).

By 1916, Baptists leapt to 55 percent of church membership, and Methodists fell to 31 percent. Roman Catholics peaked at a little more than 5 percent in 1916, enough to incite a bitter anti-Catholic backlash led by the reinvigorated Ku Klux Klan in Birmingham and by political attacks on Catholics by politicians such as U.S. senator Tom Heflin in 1928. Anti-Catholicism was not the only political issue drawing the attention of evangelicals. During the 1890s, they divided largely along class lines in support of or opposition to the Populist reform movement. Nor could they agree about the Prohibition movement, though most Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians desired some kind of restriction on the sale of alcoholic beverages. By the early twentieth century, many reform-minded Protestants, especially women, endorsed a wide range of causes, including opposition to the convict-lease system and child labor and in favor of temperance, woman suffrage, and prison and educational reforms. Liberal-minded ministers became pastors of many large, influential urban churches, provoking conflict with their more theologically conservative members. The social gospel—a theology rooted in the idea that the Kingdom of God should be constructed by devoted Christians in this world rather than at some future apocalyptic moment when Christ returned to Earth—gained substantial support. These theological controversies peaked in the 1920s in the battle between religion and science (particularly over the theory of evolution), and then receded during the 1930s, when people had the more pressing worry of daily survival during the Great Depression.

Increases in church membership emerged in the 1940s and 1950s, as the influence of Billy Graham and conservative evangelicalism swept the nation. All evangelical denominations prospered, though none so much as Baptists. In 1940, one in seven Alabamians was Baptist. By 1970, the figure was one in four.

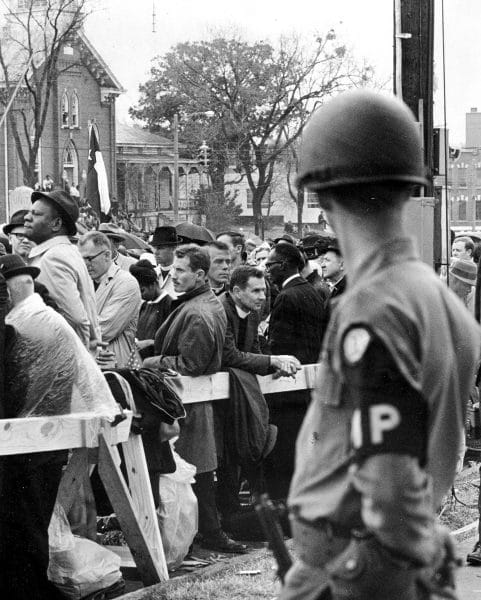

Priests in Voting Rights March

Divisions over the civil rights movement arose in both black and white churches, and many whites tried to mobilize their congregations as the last bastion of segregation in their communities. Increasing attention to so-called “culture war” issues (the content of movies, television, and popular music; abortion; and the rights of homosexuals), waning attention to evangelism, and fierce arguments about racial inclusiveness in all evangelical denominations split churches, embittered members, and finally divided denominations. The Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) withdrew from more liberal national bodies. Large numbers of segregationist Methodists left their denomination to join more conservative Southern Baptists. Episcopalians divided over adherence to the revered 1920s Prayer Book, ordination of women priests, and acceptance of homosexuality. After the 1979 conservative “takeover” or “correction” (depending on the ideology of the observer) of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), many moderate Southern Baptists left the SBC for the new Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. Despite erosion from both left and right, the Alabama Baptist State Convention remained overwhelmingly dominant among Christians. Baptisms during 2006 increased more than in any other state Baptist convention except Florida (although baptisms had peaked at 35,000 in 1972-1973 and dropped to 21,400 in 2006). Membership in Baptist churches actually has declined slightly from its peak in 2005 but still includes nearly one of every four people who live in the state (and Southern Baptist membership data does not include unbaptized children or infants). Among black Baptists, similar splits occurred between those who supported or opposed Martin Luther King’s aggressive civil disobedience and anti-war campaigns, leading to the creation of the Progressive National Baptist Convention.

Priests in Voting Rights March

Divisions over the civil rights movement arose in both black and white churches, and many whites tried to mobilize their congregations as the last bastion of segregation in their communities. Increasing attention to so-called “culture war” issues (the content of movies, television, and popular music; abortion; and the rights of homosexuals), waning attention to evangelism, and fierce arguments about racial inclusiveness in all evangelical denominations split churches, embittered members, and finally divided denominations. The Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) withdrew from more liberal national bodies. Large numbers of segregationist Methodists left their denomination to join more conservative Southern Baptists. Episcopalians divided over adherence to the revered 1920s Prayer Book, ordination of women priests, and acceptance of homosexuality. After the 1979 conservative “takeover” or “correction” (depending on the ideology of the observer) of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), many moderate Southern Baptists left the SBC for the new Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. Despite erosion from both left and right, the Alabama Baptist State Convention remained overwhelmingly dominant among Christians. Baptisms during 2006 increased more than in any other state Baptist convention except Florida (although baptisms had peaked at 35,000 in 1972-1973 and dropped to 21,400 in 2006). Membership in Baptist churches actually has declined slightly from its peak in 2005 but still includes nearly one of every four people who live in the state (and Southern Baptist membership data does not include unbaptized children or infants). Among black Baptists, similar splits occurred between those who supported or opposed Martin Luther King’s aggressive civil disobedience and anti-war campaigns, leading to the creation of the Progressive National Baptist Convention.

As both Methodists and Baptists celebrated their 200th anniversary in 2008, Southern Baptists numbered more than 1,100,000 in some 3,200 churches, and United Methodists counted 250,000 members in 1,500 churches. Meanwhile, all traditional Protestant groups lost ground to Pentecostal denominations, such as the Church of God, Church of God in Christ, Nazarene, and Assemblies of God, as well as to suburban independent megachurches unaffiliated with any denomination; these churches feature upbeat music, a casual worship style, and lots of user-friendly cells, home meetings, gymnasia, dieting support groups, and even food courts inside the churches. Although Holiness and Pentecostal churches had begun appearing in Alabama as early as the late nineteenth century, the independent megachurches were a religious phenomenon unique to the late twentieth century.

Whatever one’s religious faith (and by the early twenty-first century, Asian, Hispanic, and Middle Eastern immigrants were bringing new forms of religion into the state), more than 90 percent of Alabama residents believed in God and nearly that many in the existence of heaven and hell, Satan, and judgment. In 1996, three-quarters of the state’s adults considered themselves “born again” compared with a third nationally. They overwhelmingly believed that God created the world in a single act some 10,000 years ago. And although they were generally conservative about individual moral conduct, most were not willing to ban abortion entirely.

Yet as if to prove how difficult it is to translate abstract theology into ethical conduct, Alabamians rank near the top in divorce rates, births to unmarried women, poverty, and racial discord. They also have one of the highest rates of gifts to charity, and white churches are slowly opening their doors to people of color. Ultimately, attitudes are so complex that superficial stereotypes about religion in Alabama serve little useful purpose.

Additional Resources

Boothe, Charles O. The Cyclopedia of the Colored Baptists of Alabama. Birmingham: Alabama Publishing Co., 1895.

Collins, Donald E. When The Church Bell Rang Racist: The Methodist Church and the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1998.

Elovitz, Mark H. A Century of Jewish Life in Dixie: The Birmingham Experience. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1974.

Fallin, Wilson Jr. Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

Flynt, Wayne. Alabama Baptists: Southern Baptists in the Heart of Dixie. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998.

———. “Alabama.” In Religion in the Southern States: A Historical Study, edited by Samuel S. Hill. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1983.

Kenny, Michael. Catholic Culture in Alabama: Centenary Story of Spring Hill College, 1830-1930. New York: America Press, 1931

Lazenby, Marion E. History of Methodism in Alabama and West Florida. North Alabama Conference and Alabama-West Florida Conference of the Methodist Church, 1960.

Marshall, James W., and Robert Strong. The Presbyterian Church in Alabama. Montgomery, Ala.: Presbyterian Historical Society of Alabama, 1977.

Watson, George H., and Mildred B. Watson. History of the Christian Churches in the Alabama Area. St. Louis, Ill.: Bethany Press, 1965.

Watts, Elder E. B. A History of the Primitive Baptists of Alabama: Mount Zion Association. Altwood, Tenn.: Christian Baptist Publishing Co., 1979.