Bryce Hospital (Alabama Insane Hospital)

Bryce Hospital

Founded in Tuscaloosa in 1859 as the Alabama Insane Hospital (AIH), Bryce Hospital is one of the oldest mental health facilities in the state. Under the guidance of its first superintendent, Peter Bryce, AIH was at the forefront of mental health innovations for many years, providing patients with meaningful work opportunities that also helped fund the facility. Bryce Hospital’s reputation suffered during the latter half of the twentieth century when questionable treatment of patients prompted a court case, Wyatt v. Stickney, and a Supreme Court decision that brought about reform in mental institutions throughout the United States.

Bryce Hospital

Founded in Tuscaloosa in 1859 as the Alabama Insane Hospital (AIH), Bryce Hospital is one of the oldest mental health facilities in the state. Under the guidance of its first superintendent, Peter Bryce, AIH was at the forefront of mental health innovations for many years, providing patients with meaningful work opportunities that also helped fund the facility. Bryce Hospital’s reputation suffered during the latter half of the twentieth century when questionable treatment of patients prompted a court case, Wyatt v. Stickney, and a Supreme Court decision that brought about reform in mental institutions throughout the United States.

With urging from Dorothea Dix, a well-known crusader for professional care for the mentally ill who toured Alabama in the 1840s, and the Alabama Medical Society, the Alabama legislature and Governor Henry W. Collier enacted a law in 1852 establishing the Alabama Insane Hospital (AIH). The law addressed six major areas: state financial support, asylum governance, site selection, facility construction, superintendent selection, and patient admission. According to the legislation, funding for the creation and maintenance of the hospital was to be derived from 5 percent of the state’s annual revenue for the next four years. In what was later revealed as a serious flaw, funding for AIH in the fifth year and beyond was not addressed. Whereas state support was allocated specifically for the care of indigent patients, a provision was made for admission of “paying” patients as well.

The hospital was governed by a board of trustees. Resident trustees, who were either residents of Tuscaloosa County, where the hospital was located, or of an adjoining county and thus most accessible to the superintendent, had the most influence in decision making. The trustees were frequently called on over the years by the superintendent to help persuade the legislature to increase funding, or in many cases, not cut funding.

Bryce Hospital

In 1852, the trustees authorized the purchase of 326 acres of land in Tuscaloosa for the hospital, which would be based upon a design by Philadelphia hospital superintendent and physician Thomas Kirkbride. The building was characterized by wings on each side of a center building, with the end of each wing having extensions attached by a cross hall and with additional wings extending outward and backward in a desired configuration. The existing Bryce facility has been called the most fully realized example of the Kirkbride design, one that had achieved a national reputation in the mental hospital field. Construction began in 1853 but was interrupted by funding shortages. The facility finally was completed in 1859, and the building was the first building in the city with gas lighting and central heat.

Bryce Hospital

In 1852, the trustees authorized the purchase of 326 acres of land in Tuscaloosa for the hospital, which would be based upon a design by Philadelphia hospital superintendent and physician Thomas Kirkbride. The building was characterized by wings on each side of a center building, with the end of each wing having extensions attached by a cross hall and with additional wings extending outward and backward in a desired configuration. The existing Bryce facility has been called the most fully realized example of the Kirkbride design, one that had achieved a national reputation in the mental hospital field. Construction began in 1853 but was interrupted by funding shortages. The facility finally was completed in 1859, and the building was the first building in the city with gas lighting and central heat.

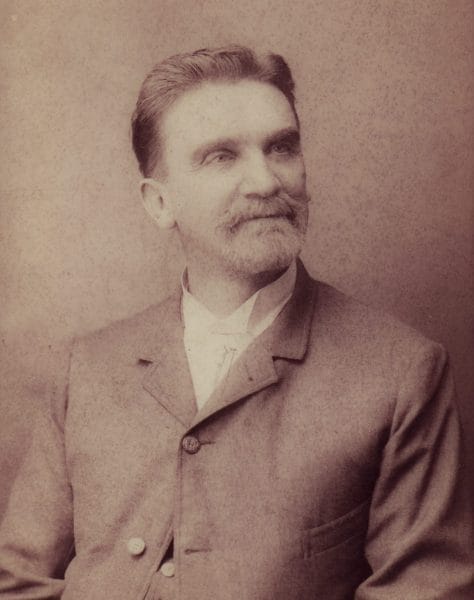

Peter Bryce

That same year, the trustees began a search for a superintendent. Dorothea Dix brought physician Peter Bryce, a South Carolina native who had studied mental health care in Europe and worked in psychiatric hospitals in New Jersey and South Carolina, to the attention of the trustees. They selected him for the position, and when the hospital opened in 1861, Bryce and his new wife moved into a house on the AIH grounds. Bryce was an unusual choice at the time because few asylum superintendents in that era were physicians. Bryce instituted a system known as the moral treatment plan, a new approach to mental health services in which mental illnesses were viewed in terms of “predisposing” causes, which were considered to be physiological defects, and “precipitating” causes, which resulted from environmental conditions in the home or society. The treatment generally involved removing patients from likely precipitating causes and establishing as much of a normal life as possible for them while allowing time for the predisposing causes to heal. Patients were therefore, if at all able, engaged in the type of work with which they were most familiar, with the goal that the work would divert their attention away from their mental condition.

Peter Bryce

That same year, the trustees began a search for a superintendent. Dorothea Dix brought physician Peter Bryce, a South Carolina native who had studied mental health care in Europe and worked in psychiatric hospitals in New Jersey and South Carolina, to the attention of the trustees. They selected him for the position, and when the hospital opened in 1861, Bryce and his new wife moved into a house on the AIH grounds. Bryce was an unusual choice at the time because few asylum superintendents in that era were physicians. Bryce instituted a system known as the moral treatment plan, a new approach to mental health services in which mental illnesses were viewed in terms of “predisposing” causes, which were considered to be physiological defects, and “precipitating” causes, which resulted from environmental conditions in the home or society. The treatment generally involved removing patients from likely precipitating causes and establishing as much of a normal life as possible for them while allowing time for the predisposing causes to heal. Patients were therefore, if at all able, engaged in the type of work with which they were most familiar, with the goal that the work would divert their attention away from their mental condition.

Bryce Hospital Laundry

Whereas a work-centered treatment program was acceptable from a medical standpoint, it soon became a necessity when state funding for the institution dropped substantially. To survive, the hospital had to produce many items for its own use and for commercial sale. Thus, for the first 30 years of the hospital’s existence, AIH supplemented meager state appropriations with income from the sale of patient-produced goods. The hospital’s success at increasing revenue however, seemed to embolden the state legislature to further reduce funding. That approach to hospital support was institutionalized and continued throughout the Bryce administration and beyond. Bryce died in 1892 and was buried on the hospital’s grounds. Eight years later, the state officially renamed the facility Bryce Hospital in his honor.

Bryce Hospital Laundry

Whereas a work-centered treatment program was acceptable from a medical standpoint, it soon became a necessity when state funding for the institution dropped substantially. To survive, the hospital had to produce many items for its own use and for commercial sale. Thus, for the first 30 years of the hospital’s existence, AIH supplemented meager state appropriations with income from the sale of patient-produced goods. The hospital’s success at increasing revenue however, seemed to embolden the state legislature to further reduce funding. That approach to hospital support was institutionalized and continued throughout the Bryce administration and beyond. Bryce died in 1892 and was buried on the hospital’s grounds. Eight years later, the state officially renamed the facility Bryce Hospital in his honor.

From Bryce’s death in 1892 until 1970, the approach to treatment at the Bryce Hospital (formerly known as the AIH) followed the concept that patient work was an important component of mental healthcare. The approach also continued to provide funding to Bryce Hospital, through the continued sale of patient-made goods. By 1970, however, the concept of patients remaining in the hospital for long periods of time while at the same time working productively became a subject of public concern, especially as many citizens felt that patients were retained by the hospital as a source of free labor. In 1972, in a class-action lawsuit in federal court, known as Wyatt v. Stickney, U.S. District Court Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. ruled that every patient has a right to periodic psychiatric evaluations and a right to live in the least restrictive environment possible. The decision had wide-ranging effects, and as a result, many patients were released from mental institutions nationwide or transferred to homes designed to provide them with as much independence as feasible.

Although Bryce Hospital was not intentionally on the forefront of psychiatric care, its storied history reflects the changes in attitude of psychiatric professionals and the public toward mental illness and mental health care. Bryce Hospital continues to be an important center for mental-health treatment in Alabama, but its fate remains uncertain. In early 2008, the University of Alabama initiated efforts to buy the facility. The sale faces several hurdles and has aroused concerns among preservationists about the fate of the historic Bryce campus.

Autoclave at Bryce Hospital

In April 2008, Alabama mental health commissioner John Houston established the Bryce Hospital Historic Preservation Committtee, chaired by Thomas Hobbs, executive director of the Western Mental Health Center in Ensley. Houston charged the committee with recommending ways to preserve and manage historically significant structures, documents, and artifacts relating to Bryce Hospital, its staff, and its patients. The Alabama Department of Mental Health has hired a historian to coordinate the preservation efforts, and the committee is planning a Bryce Hospital Museum, which will focus on tourism and research, and is in the process of soliciting donations of items and collecting oral histories from people associated with Bryce.

Autoclave at Bryce Hospital

In April 2008, Alabama mental health commissioner John Houston established the Bryce Hospital Historic Preservation Committtee, chaired by Thomas Hobbs, executive director of the Western Mental Health Center in Ensley. Houston charged the committee with recommending ways to preserve and manage historically significant structures, documents, and artifacts relating to Bryce Hospital, its staff, and its patients. The Alabama Department of Mental Health has hired a historian to coordinate the preservation efforts, and the committee is planning a Bryce Hospital Museum, which will focus on tourism and research, and is in the process of soliciting donations of items and collecting oral histories from people associated with Bryce.

Additional Resources

Alabama Department of Mental Health. “Voices and Visions: Bryce Historical Committee Members Explore Their Hopes for Bryce.” Listen (Winter 2009), entire issue.

Weaver, Bill. “Establishing and Organizing the Alabama Insane Hospital, 1846-1861.” Alabama Review 47 (July 1995): 219–32.

———. “Survival at the Alabama Insane Hospital, 1861–1892.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 51 (January 1996): 5–28.