Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) was an author, folklorist, journalist, dramatist, and influential member of the Harlem Renaissance. She is best known for her novels, particularly Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). A complex and controversial figure, Hurston was an ardent promoter of African American culture. Although criticized by her peers, who were interested in using literature and art as vehicles for overcoming stereotypes and promoting integration, assimilation, and equality, Hurston refused to concentrate on racism in her writing. Hurston’s short stories, plays, and novels reflect her interest in anthropology and make use of the material she collected while working on various funded expeditions around the South and in Haiti and Jamaica.

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) was an author, folklorist, journalist, dramatist, and influential member of the Harlem Renaissance. She is best known for her novels, particularly Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). A complex and controversial figure, Hurston was an ardent promoter of African American culture. Although criticized by her peers, who were interested in using literature and art as vehicles for overcoming stereotypes and promoting integration, assimilation, and equality, Hurston refused to concentrate on racism in her writing. Hurston’s short stories, plays, and novels reflect her interest in anthropology and make use of the material she collected while working on various funded expeditions around the South and in Haiti and Jamaica.

The controversy surrounding Hurston begins with the place of her birth. Notasulga, located in both Macon and Lee Counties, and Eatonville, Florida, both vie for the honor, but Notasulga, in east-central Alabama, is currently accepted by most scholars. She was born on January 7, 1891, to John Hurston and Lucy Potts Hurston, who was from a landowning family and had taught school before marrying. The Potts family, according to Hurston in her autobiography, Dirt Tracks on a Road, did not approve of the marriage because the groom’s prospects were poor, but John and Lucy wed, farmed, and started their own family. Zora was the fifth child, and when she was a toddler, they moved to the all-black town of Eatonville. There, John became a carpenter and a Baptist preacher, and he was elected mayor. Lucy Hurston died in 1904, and Hurston was sent to a boarding school in Jacksonville, Florida, where she was a successful and enthusiastic student. John remarried, and because Zora and her new stepmother disliked each other, Hurston lived with several relatives. She supported herself as a domestic before going to live with a brother in Baltimore, graduating from the city’s Morgan Academy in June 1918. Disappointed by her brother’s unwillingness to allow her to continue her education, Hurston found work with a traveling entertainment company. She earned $10 a week performing chores for her employer (whom she later wrote about in Dust Tracks on a Road as Miss M) and other members of the company. They loaned Hurston books, exposed her to classical music, and included her in discussions. When Miss M decided to leave the stage and marry, Hurston returned to Baltimore.

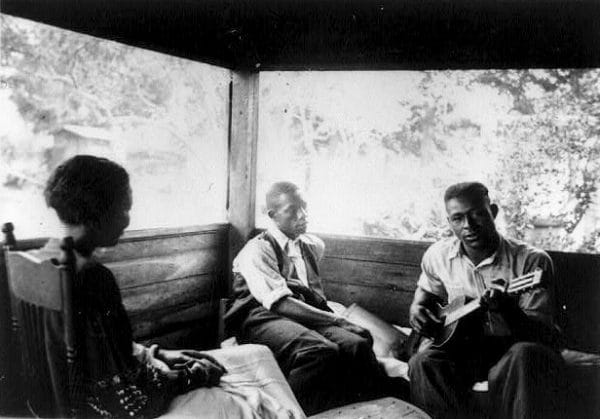

Zora N. Hurston, Rochelle French, and Gabriel Brown

By June 1918, Hurston had finished high school at Morgan Academy in Baltimore and entered Howard University, completing an associate degree in 1920. For the next few years, she wrote and published short stories. In 1925, Hurston entered Barnard College in New York, where she developed an interest in anthropology. Barnard professor and anthropologist Franz Boas encouraged her to do field work collecting data on stories, folkways, language, superstitions, visions, music, and religious practices from African Americans who were migrating out of the Jim Crow South to New York’s Harlem neighborhood. There, she met author and columnist Langston Hughes and other writers and artists who would become the architects of what became known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Zora N. Hurston, Rochelle French, and Gabriel Brown

By June 1918, Hurston had finished high school at Morgan Academy in Baltimore and entered Howard University, completing an associate degree in 1920. For the next few years, she wrote and published short stories. In 1925, Hurston entered Barnard College in New York, where she developed an interest in anthropology. Barnard professor and anthropologist Franz Boas encouraged her to do field work collecting data on stories, folkways, language, superstitions, visions, music, and religious practices from African Americans who were migrating out of the Jim Crow South to New York’s Harlem neighborhood. There, she met author and columnist Langston Hughes and other writers and artists who would become the architects of what became known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Hurston’s dream was that their efforts would preserve and promote the traditional dialects and cultural heritage of rural southern black people; although she and other intellectuals envisioned more and better opportunities for African Americans, Hurston differed in that she resisted the idea of trading black culture for economic and social equality. Langston Hughes accused her of catering to white audiences and of allowing white patronage to affect her work; her defense against such accusations was that she chose to create characters memorable for their unapologetic celebration of black heritage. Her stance was one of affirmation. Fearful, perhaps, that integration would threaten black cultural traditions, Hurston opposed desegregation. This position was unpopular and misunderstood by those seeking social change. Aware of racism, racially motivated violence, and the degradation of Jim Crow laws, Hurston nonetheless did not launch a frontal attack. She understood the problems experienced by African Americans and women in the first half of the twentieth century, but she perceived that portrayals of them as helpless victims would perpetuate a sense of inferiority. Using Eatonville porch stories and material from collecting excursions, she recorded vibrant black life and the will to survive in a hostile environment, and she dealt with bitterness and resentment about injustice in subtle ways. Her characters are proud, independent, confident, and resourceful; they represent a healthy culture that Hurston did not want subsumed or assimilated. She championed diversity. Hers were ordinary people too busy living to spend much time feeling oppressed or demanding pity or sympathy from a dominant culture whose values were questionable.

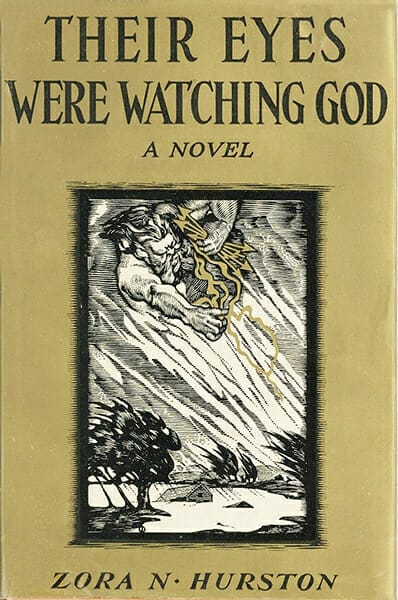

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Some Harlem Renaissance artists believed that it was their duty to create literature, art, and music that promoted assimilation into white mainstream American culture. Hurston drew criticism from some African American intellectuals, including novelist Richard Wright, for writing dialogue in rural African American dialect and for presenting her characters in ways that other writers and critics considered backward or inappropriate. Her writing also met with criticism from some white literary reviewers, who felt that her characters were stereotypes. Her friendship with Langston Hughes ended over a disagreement about writing credits for Mule Bone, a play on which they had collaborated.

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Some Harlem Renaissance artists believed that it was their duty to create literature, art, and music that promoted assimilation into white mainstream American culture. Hurston drew criticism from some African American intellectuals, including novelist Richard Wright, for writing dialogue in rural African American dialect and for presenting her characters in ways that other writers and critics considered backward or inappropriate. Her writing also met with criticism from some white literary reviewers, who felt that her characters were stereotypes. Her friendship with Langston Hughes ended over a disagreement about writing credits for Mule Bone, a play on which they had collaborated.

Hurston graduated from Barnard in 1928 and embarked on a successful career as a playwright. She wrote and directed musical, dance, and dramatic productions that employed black talent and emphasized African American culture and contributions to U.S. history and society and were performed in New York, Florida, and Chicago. In 1934, she published her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine. That same year, the Rosenwald Foundation offered her a fellowship to enter the doctoral program in anthropology at Columbia University; she accepted the fellowship but never completed the degree. Instead, using field notes that she had collected in New Orleans and Florida in 1927, she wrote Mules and Men, which she published in 1935. On the strength of that and her other accomplishments, she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to study West Indian folklife in Haiti. While there, she wrote her most famous novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, which was published in 1937. She published Tell My Horse, based on her experiences in Haiti, in 1938, and in 1941 wrote an autobiography entitled Dust Tracks on a Road.

None of Hurston’s novels met with absolute acclaim. Some critics praised her honesty, accepting the simplicity and humor in her writing as evidence of black contentment; others deplored her reluctance to address racial conflict and bitterness. Publishers were partly to blame because they edited out passages and requested that she delete some controversial social and political observations. Even Their Eyes Were Watching God, generally recognized as Hurston’s best work, was not considered serious enough by some reviewers. There was universal agreement, however, that she was gifted at capturing and retelling the stories of common people. Her last book, Seraph on the Suwanee, was published in 1948, but it received poor reviews.

Zora Neale Hurston, 1937

That same year, she was humiliated publicly by a false accusation of molesting a young boy. In 1950, she relocated to Florida and wrote essays and took odd jobs to make ends meet. In 1952, the Pittsburgh Courier hired Hurston to cover the murder trial of Ruby McCollum in Live Oak, Florida. McCollum, an African American woman, had shot and killed a white man, C. LeRoy Adams, who was a popular local physician with political ambitions in the small segregated town. McCollum claimed to have been carrying Adams’s child and to have suffered years of mental and physical abuse from him, but her efforts to tell her version of the events leading to the slaying were ignored. The trial attracted the attention of the national media, and Hurston’s accounts provided insights about a conspiracy to thwart justice. Fellow Alabamian William Bradford Huie later drew heavily on Hurston’s observations in his book, Ruby McCollum: Woman in the Suwanee Jail, published in 1964. Huie and Hurston had corresponded about the trial, the town’s rigorous silence, racial tension, and the fate of McCollum, and Hurston seemed to have rediscovered her literary voice through reporting on the case.

Zora Neale Hurston, 1937

That same year, she was humiliated publicly by a false accusation of molesting a young boy. In 1950, she relocated to Florida and wrote essays and took odd jobs to make ends meet. In 1952, the Pittsburgh Courier hired Hurston to cover the murder trial of Ruby McCollum in Live Oak, Florida. McCollum, an African American woman, had shot and killed a white man, C. LeRoy Adams, who was a popular local physician with political ambitions in the small segregated town. McCollum claimed to have been carrying Adams’s child and to have suffered years of mental and physical abuse from him, but her efforts to tell her version of the events leading to the slaying were ignored. The trial attracted the attention of the national media, and Hurston’s accounts provided insights about a conspiracy to thwart justice. Fellow Alabamian William Bradford Huie later drew heavily on Hurston’s observations in his book, Ruby McCollum: Woman in the Suwanee Jail, published in 1964. Huie and Hurston had corresponded about the trial, the town’s rigorous silence, racial tension, and the fate of McCollum, and Hurston seemed to have rediscovered her literary voice through reporting on the case.

During the last 10 years of her life, Hurston continued to write essays that reflected her complex views on integration. In them, she advocated segregation as a means of preserving African American cultural traditions. Hurston’s final years were plagued by financial worries and declining health. With little work coming her way after the false molestation charges, she worked as a maid in Rivo Alto, Florida, and struggled to find work throughout the 1950s. In 1959, Hurston was admitted to a nursing home in Fort Pierce after she suffered a stroke. She died there of a heart attack on January 28, 1960, and was buried in an unmarked grave. Author Alice Walker, who counted Hurston as a primary influence in her own writing, revived interest in Hurston when she searched out Hurston’s grave, provided a headstone for it, and published an article entitled “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” in Ms. magazine in 1975.

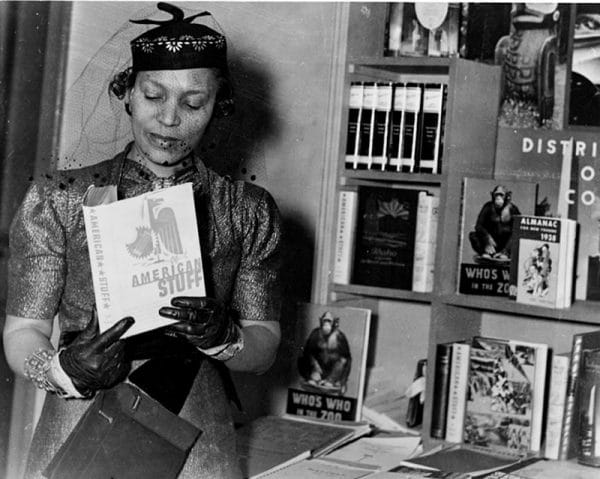

Zora Neale Hurston, 1938

Although Hurston remains a controversial figure, she is remembered for her ability to make herself heard at a time when most women—especially African American women—were expected to be silent and submissive. The Florida cities of Fort Pierce and Eatonville now host annual festivals to commemorate Hurston’s life and literary achievements. Her short story “The Gilded Six Bits” was made into a short film in 2001, and her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God was released as a film for television in 2005. Hurston’s life was marked by triumph and disappointment. During the turbulent years of the Great Depression, she produced five of her seven books, but by the time of her death, none remained in print. Due in large part to the efforts of Alice Walker, Hurston scholarship has been revived. Once denounced as entertainment fiction, Hurston’s work now enjoys a secure place in twentieth-century literature. She defied conventions and upheld human dignity, and her views are being reassessed by a new generation of readers and researchers.

Zora Neale Hurston, 1938

Although Hurston remains a controversial figure, she is remembered for her ability to make herself heard at a time when most women—especially African American women—were expected to be silent and submissive. The Florida cities of Fort Pierce and Eatonville now host annual festivals to commemorate Hurston’s life and literary achievements. Her short story “The Gilded Six Bits” was made into a short film in 2001, and her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God was released as a film for television in 2005. Hurston’s life was marked by triumph and disappointment. During the turbulent years of the Great Depression, she produced five of her seven books, but by the time of her death, none remained in print. Due in large part to the efforts of Alice Walker, Hurston scholarship has been revived. Once denounced as entertainment fiction, Hurston’s work now enjoys a secure place in twentieth-century literature. She defied conventions and upheld human dignity, and her views are being reassessed by a new generation of readers and researchers.

Works by Zora Neale Hurston

Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934)

Mules and Men (1935)

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica (1938)

Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939)

Dust Tracks on a Road (1942)

Seraph on the Suwanee (1948)

The Sanctified Church: The Folklore Writings of Zora Neale Hurston (1981)

Spunk: The Selected Stories (1985)

Further Reading

- Bloom, Harold, ed. Zora Neale Hurston. New York: Chelsea House, 1986.

- Green, Sharony. The Chase and Ruins: Zora Neale Hurston in Honduras. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023.

- Hemenway, Robert E. Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977.

- Kaplan, Carla. Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters. New York: Anchor Books, 2003.