Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company

Alabama Dry Dock & Shipbuilding Company

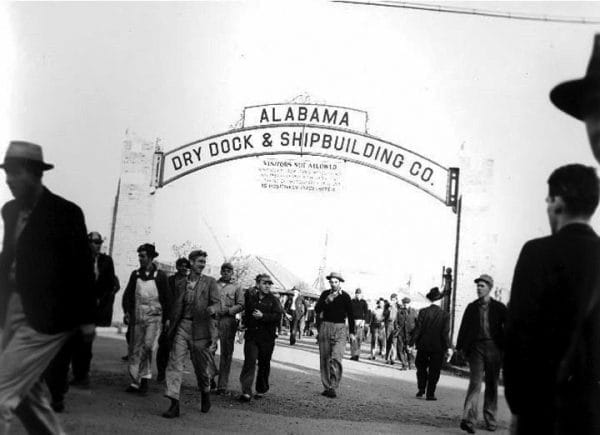

The Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company (ADDSCO) was an important component of Mobile‘s economy for 70 years. The company built and maintained U.S. Navy ships during World War I and World War II, and was the site of a race riot in 1943. ADDSCO’s facilities served as the construction site for both the Bankhead and Wallace tunnels. At its peak, the now-defunct ADDSCO was the largest employer in Mobile, with some 30,000 workers.

Alabama Dry Dock & Shipbuilding Company

The Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company (ADDSCO) was an important component of Mobile‘s economy for 70 years. The company built and maintained U.S. Navy ships during World War I and World War II, and was the site of a race riot in 1943. ADDSCO’s facilities served as the construction site for both the Bankhead and Wallace tunnels. At its peak, the now-defunct ADDSCO was the largest employer in Mobile, with some 30,000 workers.

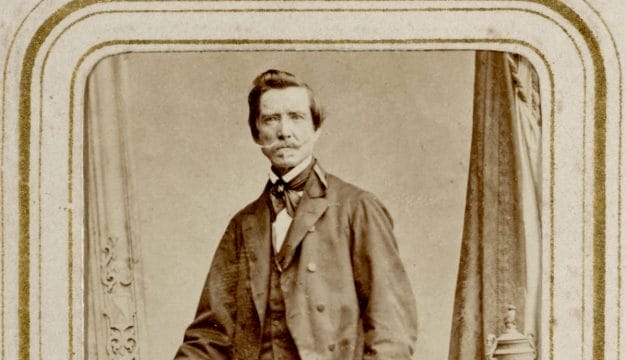

ADDSCO Founder David R. Dunlap, 1920

The company was founded in December 1916 when D. R. Dunlap, president of Alabama Iron Works, and his cousin, George H. Dunlap, bought and consolidated several smaller dry-dock companies, which provided facilities for shipping companies and related industries and government agencies to raise ships out of the water to make repairs and check for damage. This consolidation and expansion improved Mobile’s port facilities and contributed to the increase in its ship repair industries in the months before U.S. entry into World War I. At the outbreak of the war, ADDSCO employed some 4,000 people, who worked as welders, electricians, and engineers. A majority of the workers were white males. The company only employed African Americans in lower-level jobs or as assistants to white welders. Most of ADDSCO’s early repair and shipbuilding work was done at the company’s two large dry docks on Pinto Island, just north of downtown Mobile, where employees constructed two steam vessels, two barges, and three minesweepers.

ADDSCO Founder David R. Dunlap, 1920

The company was founded in December 1916 when D. R. Dunlap, president of Alabama Iron Works, and his cousin, George H. Dunlap, bought and consolidated several smaller dry-dock companies, which provided facilities for shipping companies and related industries and government agencies to raise ships out of the water to make repairs and check for damage. This consolidation and expansion improved Mobile’s port facilities and contributed to the increase in its ship repair industries in the months before U.S. entry into World War I. At the outbreak of the war, ADDSCO employed some 4,000 people, who worked as welders, electricians, and engineers. A majority of the workers were white males. The company only employed African Americans in lower-level jobs or as assistants to white welders. Most of ADDSCO’s early repair and shipbuilding work was done at the company’s two large dry docks on Pinto Island, just north of downtown Mobile, where employees constructed two steam vessels, two barges, and three minesweepers.

Construction of the Bankhead Tunnel

After World War I, company workers constructed the Bankhead Tunnel (named for Alabama politician John Hollis Bankhead), which was paid for with funds from the Works Progress Administration. Workers built the tunnel in seven 300-foot sections at the dry dock and then assembled the tunnel underwater in February 1941. The tunnel made it easier for Mobilians to access the road connecting Mobile and Baldwin County. In the interwar years, ADDSCO worked on small repair contracts, but the majority of construction during the period focused on the Bankhead Tunnel.

Construction of the Bankhead Tunnel

After World War I, company workers constructed the Bankhead Tunnel (named for Alabama politician John Hollis Bankhead), which was paid for with funds from the Works Progress Administration. Workers built the tunnel in seven 300-foot sections at the dry dock and then assembled the tunnel underwater in February 1941. The tunnel made it easier for Mobilians to access the road connecting Mobile and Baldwin County. In the interwar years, ADDSCO worked on small repair contracts, but the majority of construction during the period focused on the Bankhead Tunnel.

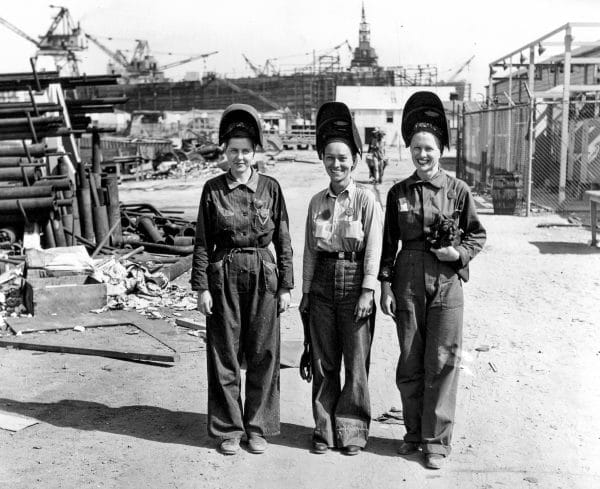

Women Welders, ca. 1944

With U.S. involvement in World War II, ADDSCO shifted again to wartime production. The company quickly became the city’s largest employer of war workers, as demand for ships increased. The number of employees grew to approximately 30,000 by 1943. In July 1942, ADDSCO began hiring white women as nonclerical workers at its Pinto Island facility. By September, nearly 100 women worked as welders. By the end of the war, ADDSCO employed 2,500 female workers. Officials were slower to employ African Americans in large numbers, however. The company did not employee African American women until after the war. In 1941, the company hired African American men in nonskilled positions.

Women Welders, ca. 1944

With U.S. involvement in World War II, ADDSCO shifted again to wartime production. The company quickly became the city’s largest employer of war workers, as demand for ships increased. The number of employees grew to approximately 30,000 by 1943. In July 1942, ADDSCO began hiring white women as nonclerical workers at its Pinto Island facility. By September, nearly 100 women worked as welders. By the end of the war, ADDSCO employed 2,500 female workers. Officials were slower to employ African Americans in large numbers, however. The company did not employee African American women until after the war. In 1941, the company hired African American men in nonskilled positions.

ADDSCO Welders

In 1942, Roosevelt’s Fair Employment Practices Committee issued directives to elevate some African Americans to skilled positions, but ADDSCO officials were slow to meet this requirement. As late as May 1943, management maintained completely segregated facilities. Their efforts failed, however, and 12 African Americans were upgraded to welders and added to all-white crews. On May 24, 1943, a race riot erupted at ADDSCO during the night shift. All of the African American employees were driven from the yard, and the National Guard was called in to restore order. Several weeks passed before African American workers could safely return to work.

ADDSCO Welders

In 1942, Roosevelt’s Fair Employment Practices Committee issued directives to elevate some African Americans to skilled positions, but ADDSCO officials were slow to meet this requirement. As late as May 1943, management maintained completely segregated facilities. Their efforts failed, however, and 12 African Americans were upgraded to welders and added to all-white crews. On May 24, 1943, a race riot erupted at ADDSCO during the night shift. All of the African American employees were driven from the yard, and the National Guard was called in to restore order. Several weeks passed before African American workers could safely return to work.

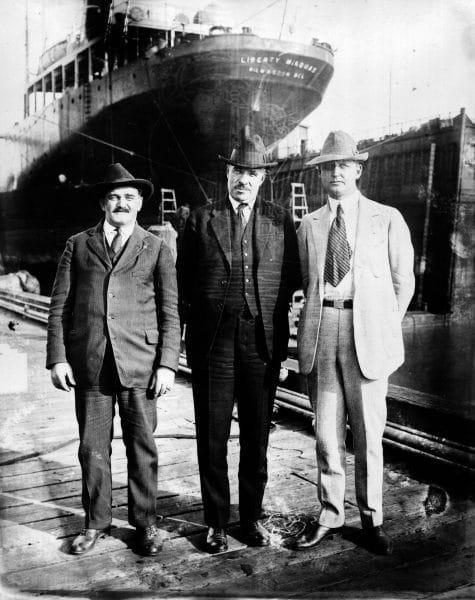

Arickaree at ADDSCO

One of ADDSCO’s first wartime contracts was for 20 Liberty Ships, slow-moving cargo vessels used for mass-transportation of goods and men. After completing the order in October 1942, the company began building oil tankers. The first tanker, the Arickaree, was the largest vessel ever built along the Gulf Coast. The company eventually built 102 tankers and refitted an additional 2,800 vessels for combat before the end of the war, which brought an end to the shipbuilding boom in Mobile. After the end of the war in April 1945, ADDSCO began laying off its wartime employees by the thousands each month. Many of them returned to their homes in Mississippi and Alabama’s interior. Mobile’s economy was sluggish after World War II, and many construction workers sought employment outside the city. By the 1960s, ADDSCO had only about 2,000 employees.

Arickaree at ADDSCO

One of ADDSCO’s first wartime contracts was for 20 Liberty Ships, slow-moving cargo vessels used for mass-transportation of goods and men. After completing the order in October 1942, the company began building oil tankers. The first tanker, the Arickaree, was the largest vessel ever built along the Gulf Coast. The company eventually built 102 tankers and refitted an additional 2,800 vessels for combat before the end of the war, which brought an end to the shipbuilding boom in Mobile. After the end of the war in April 1945, ADDSCO began laying off its wartime employees by the thousands each month. Many of them returned to their homes in Mississippi and Alabama’s interior. Mobile’s economy was sluggish after World War II, and many construction workers sought employment outside the city. By the 1960s, ADDSCO had only about 2,000 employees.

Liberty Ship USS Fort Laramie at ADDSCO

ADDSCO continued to be primarily a repair facility until 1967, when it received a contract from the U.S. Navy to build rescue ships, which were outfitted with life-saving equipment for crews on endangered vessels in deep sea waters. The contract provided a significant boost to Mobile’s sagging economy. The project continued until 1972 and eventually employed 600 additional workers at the facility. The shipyard also contributed to other maritime projects. In 1970, ADDSCO workers completed construction of the George Wallace Tunnel on Interstate 10. The shipyard then partnered with three other shipping industries to transform the tanker Manhattan into the world’s largest ice-breaking ship. The vessel navigated the frozen Northwest Passage and effectively opened the sea route to Alaskan oil fields. During the late 1970s, ADDSCO constructed four semi-submersible oil platforms for the Coral Drilling Company in the Gulf of Mexico.

Liberty Ship USS Fort Laramie at ADDSCO

ADDSCO continued to be primarily a repair facility until 1967, when it received a contract from the U.S. Navy to build rescue ships, which were outfitted with life-saving equipment for crews on endangered vessels in deep sea waters. The contract provided a significant boost to Mobile’s sagging economy. The project continued until 1972 and eventually employed 600 additional workers at the facility. The shipyard also contributed to other maritime projects. In 1970, ADDSCO workers completed construction of the George Wallace Tunnel on Interstate 10. The shipyard then partnered with three other shipping industries to transform the tanker Manhattan into the world’s largest ice-breaking ship. The vessel navigated the frozen Northwest Passage and effectively opened the sea route to Alaskan oil fields. During the late 1970s, ADDSCO constructed four semi-submersible oil platforms for the Coral Drilling Company in the Gulf of Mexico.

ADDSCO continued its work in repairing vessels into the late 1980s, until a series of accidents put the future of the shipyard in jeopardy. In July 1988, a 40-foot portion of the facility was damaged by a docking ship. That same month, the docks were further damaged by a large wave from the wake of a passing ship. In October 1988, ADDSCO officials announced the facility would close, eliminating about 400 jobs. The facility was divided and sold to several out-of-state companies during the 1990s. Shortly after the closing, 1,000 former employees filed a class-action lawsuit to secure their pensions, reaching a settlement in 1992.

ADDSCO Docks on Pinto Island

The Alabama Dry Dock Shipbuilding Corporation was a major component of the maritime industry of Mobile for much of the twentieth century. ADDSCO, combined with the facilities of the Alabama State Docks and the Waterman Steamship Corporation, transformed Mobile into a shipping and shipbuilding center along the Gulf Coast. Travelers still benefit from the company’s efforts every day as they commute through Mobile’s two traffic tunnels. ADDSCO will be remembered for its efforts to improve Mobile’s economy and its contributions to America’s maritime history.

ADDSCO Docks on Pinto Island

The Alabama Dry Dock Shipbuilding Corporation was a major component of the maritime industry of Mobile for much of the twentieth century. ADDSCO, combined with the facilities of the Alabama State Docks and the Waterman Steamship Corporation, transformed Mobile into a shipping and shipbuilding center along the Gulf Coast. Travelers still benefit from the company’s efforts every day as they commute through Mobile’s two traffic tunnels. ADDSCO will be remembered for its efforts to improve Mobile’s economy and its contributions to America’s maritime history.

Further Reading

- Cronenburg, Allen. Forth to the Mighty Conflict: Alabama and World War II. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Nelson, Bruce. “Organized Labor and the Struggle for Black Equality in Mobile During World War II.” Journal of American History 80 (December 1993): 92-98.

- Olliff, Martin, ed. The Great War in the Heart of Dixie: Alabama in World War I. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

- ADDSCO Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama, Mobile, Alabama.