Scottsboro Trials

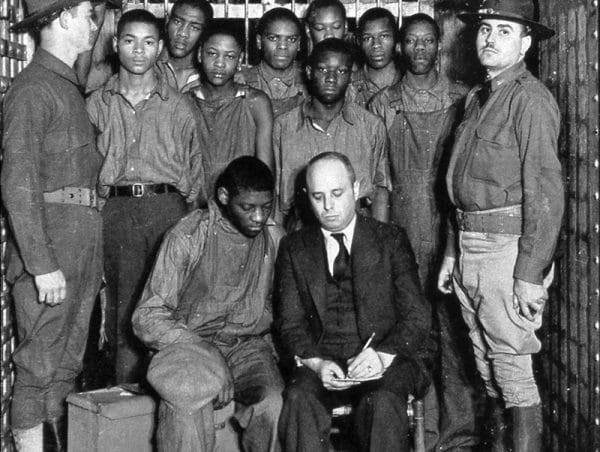

Scottsboro Trial Defendants

The Scottsboro Trials were among the most infamous episodes of legal injustice in the Jim Crow South. The events that culminated in the trials began in the early spring of 1931, when nine young black men were falsely accused of raping two white women on a train. The cases were tried and appealed in Alabama and twice argued before the U.S. Supreme Court. Despite evidence that exonerated the accused and even a retraction by one of the accusers, the state pursued the case and all-white juries delivered guilty verdicts that initially carried the death penalty. Several of the accused were sentenced to prison terms and all endured long stays in prison as the case made its way through the legal system. The case later served as one of the inspirations for Harper Lee‘s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel To Kill a Mockingbird.

Scottsboro Trial Defendants

The Scottsboro Trials were among the most infamous episodes of legal injustice in the Jim Crow South. The events that culminated in the trials began in the early spring of 1931, when nine young black men were falsely accused of raping two white women on a train. The cases were tried and appealed in Alabama and twice argued before the U.S. Supreme Court. Despite evidence that exonerated the accused and even a retraction by one of the accusers, the state pursued the case and all-white juries delivered guilty verdicts that initially carried the death penalty. Several of the accused were sentenced to prison terms and all endured long stays in prison as the case made its way through the legal system. The case later served as one of the inspirations for Harper Lee‘s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel To Kill a Mockingbird.

The saga began on March 25, 1931, when a fight broke out between groups of young black and white passengers riding a freight train through Jackson County. The white boys were forced from the train and wired ahead to the next stop on the line to have the black youths apprehended. When the train stopped just outside the town of Paint Rock, local police and a mob apprehended nine African Americans ranging in age from 13 to 20. Only four of the young men knew each other and were traveling together. The police also questioned Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, two white women who also were hitching a ride on the train looking for work. In the hope of avoiding vagrancy and morality charges, the women falsely accused the nine young black men—Olen Montgomery, Clarence Norris, Haywood Patterson, Ozie Powell, Willie Roberson, Charlie Weems, Eugene Williams, and brothers Andy and Roy Wright—of rape. The accused were arrested and transported to Scottsboro, the Jackson County seat, to await trial.

Over the next seven years, as the case made its way through the state and federal judicial system, “Scottsboro” became an international cause célèbre that dramatically encapsulated the American South’s troubled post-Reconstruction history of legal and extralegal racial violence, the social and political upheaval of the Great Depression, and the lingering cultural divide between North and South. In the process, the Scottsboro case in many ways inaugurated the modern civil rights movement.

The first set of trials took place in four groups over the course of just four days in early April 1931. Thousands of angry whites gathered outside the courthouse to monitor the proceedings and at the request of the local sheriff, Gov. Benjamin Meek Miller sent the Alabama National Guard to Scottsboro to prevent a lynching. Before an all-white jury and a hostile judge, the defendants’ court-appointed attorney put up a meager defense, repeatedly declining to cross-examine witnesses and failing to scrutinize the prosecution’s key pieces of evidence. Each of the four juries returned guilty verdicts in a matter of hours. Eight defendants were sentenced to death, but the jury split over whether to sentence the youngest defendant, 13-year-old Roy Wright, to death or life imprisonment, and a mistrial was declared. Wright remained in prison, awaiting the verdicts in the trials of his co-defendants, until 1937. The judge set the executions for July 10, the earliest possible date the law would allow.

Ruby Bates

The case might have ended there were it not for the intervention of the International Labor Defense (ILD), a radical legal-action organization sponsored by the Communist Party USA. The ILD recognized the case’s potential to become a lightning rod for a national struggle against racism, as well as a powerful propaganda vehicle and recruitment tool for the Communist Party. ILD lawyers quickly won the trust of the defendants and their parents, as well as a stay of execution until the case could be reviewed by the Alabama Supreme Court. This action was aided by a flood of letters from non-Communists, black and white, from across the country who learned of the case through ILD promotional efforts. The participation of the Communist-affiliated group significantly intensified the already charged atmosphere in Alabama and around the nation. Meanwhile, the nation’s leading African American civil rights organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), reacted slowly to the case because of initial doubts about the defendants’ innocence. Bitter rivals, the ILD and NAACP would battle for control of both the legal defense and the hearts and minds of African Americans for the duration of the case. For their part, Alabama officials defended the verdicts and wanted no interference by either outside organization in what they considered a local affair.

Ruby Bates

The case might have ended there were it not for the intervention of the International Labor Defense (ILD), a radical legal-action organization sponsored by the Communist Party USA. The ILD recognized the case’s potential to become a lightning rod for a national struggle against racism, as well as a powerful propaganda vehicle and recruitment tool for the Communist Party. ILD lawyers quickly won the trust of the defendants and their parents, as well as a stay of execution until the case could be reviewed by the Alabama Supreme Court. This action was aided by a flood of letters from non-Communists, black and white, from across the country who learned of the case through ILD promotional efforts. The participation of the Communist-affiliated group significantly intensified the already charged atmosphere in Alabama and around the nation. Meanwhile, the nation’s leading African American civil rights organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), reacted slowly to the case because of initial doubts about the defendants’ innocence. Bitter rivals, the ILD and NAACP would battle for control of both the legal defense and the hearts and minds of African Americans for the duration of the case. For their part, Alabama officials defended the verdicts and wanted no interference by either outside organization in what they considered a local affair.

The ILD pursued the case through the conventional legal channels of state and federal courts of appeal. However, it did not believe that justice could be secured through litigation alone. As a result, the group mounted a relentless media campaign, sponsoring rallies, parades, and nationwide speaking tours designed to raise money for the defense and to expose the gross inequities in the Alabama justice system to the court of public opinion. ILD publicity efforts transformed the case from a local matter into an international spectacle. “Scottsboro” united radicals, liberals, and moderates, as well as blacks and whites, in a common—if often contentious—alliance and inspired a host of songs, dramas, artwork, and poetry from left-wing artists around the world.

In the courtroom, the ILD appealed the case before the Alabama Supreme Court, which upheld the convictions. The group then turned to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in November 1932 overrode the Alabama decisions and granted new trials to all of the defendants. In the process, Powell v. Alabama, as the Supreme Court’s ruling was labeled, established a key precedent for enforcing African Americans’ right to adequate counsel under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Scottsboro Trial

At the state and circuit court levels however, the legal campaign to free the Scottsboro defendants met with repeated frustration and disappointment despite overwhelming evidence of the defendants’ innocence. The most persuasive evidence came from one of the accusers herself, Ruby Bates. In the break between the first set of trials and lead defendant Haywood Patterson’s second trial, which began in March 1933, Bates recanted her story and agreed to testify for the defense, admitting that Price concocted the story to avoid charges for vagrancy and crossing state lines for “immoral purposes” in violation of the Mann Act. She later marched in protests and spoke at rallies for the accused. In addition, Samuel Liebowitz, the ILD’s non-Communist lead attorney, found numerous inconsistencies in Price’s testimony and highlighted the medical examinations of Price and Bates, which refuted the pair’s charge of rape. But once more the jury returned a guilty verdict and recommended the death penalty. Then, in an act of incredible courage, Judge James Horton overrode the jury’s verdict. Horton had carefully reviewed the evidence and met privately with one of the medical examiners, who told him he thought the girls were lying. Lawyers for the state, however, continued to pursue the case, this time under a judge sympathetic to the prosecution. In December 1933, Haywood Patterson and Clarence Norris were convicted of rape and sentenced to death for a third time by another all-white jury. Five other defendants remained in prison, awaiting new trials, while the remaining two were removed to juvenile court and later convicted. In June 1934, the Alabama Supreme Court once again upheld the convictions of Patterson and Norris.

Scottsboro Trial

At the state and circuit court levels however, the legal campaign to free the Scottsboro defendants met with repeated frustration and disappointment despite overwhelming evidence of the defendants’ innocence. The most persuasive evidence came from one of the accusers herself, Ruby Bates. In the break between the first set of trials and lead defendant Haywood Patterson’s second trial, which began in March 1933, Bates recanted her story and agreed to testify for the defense, admitting that Price concocted the story to avoid charges for vagrancy and crossing state lines for “immoral purposes” in violation of the Mann Act. She later marched in protests and spoke at rallies for the accused. In addition, Samuel Liebowitz, the ILD’s non-Communist lead attorney, found numerous inconsistencies in Price’s testimony and highlighted the medical examinations of Price and Bates, which refuted the pair’s charge of rape. But once more the jury returned a guilty verdict and recommended the death penalty. Then, in an act of incredible courage, Judge James Horton overrode the jury’s verdict. Horton had carefully reviewed the evidence and met privately with one of the medical examiners, who told him he thought the girls were lying. Lawyers for the state, however, continued to pursue the case, this time under a judge sympathetic to the prosecution. In December 1933, Haywood Patterson and Clarence Norris were convicted of rape and sentenced to death for a third time by another all-white jury. Five other defendants remained in prison, awaiting new trials, while the remaining two were removed to juvenile court and later convicted. In June 1934, the Alabama Supreme Court once again upheld the convictions of Patterson and Norris.

Scottsboro Defendants

Following this latest round of guilty verdicts, ILD attorneys attempted to bribe Victoria Price in a foolish act of desperation. When the bribe came to light, Liebowitz, whose relationship with the ILD was always tenuous, severed ties with the group and established his own rival defense organization, the American Scottsboro Committee (ASC). The attempted bribe and the departure of Liebowitz marked the beginning of the end for the ILD as the leader of the Scottsboro legal defense. Eventually, the ILD would become a junior partner in a third organization, a liberal coalition called the Scottsboro Defense Committee (SDC).

Scottsboro Defendants

Following this latest round of guilty verdicts, ILD attorneys attempted to bribe Victoria Price in a foolish act of desperation. When the bribe came to light, Liebowitz, whose relationship with the ILD was always tenuous, severed ties with the group and established his own rival defense organization, the American Scottsboro Committee (ASC). The attempted bribe and the departure of Liebowitz marked the beginning of the end for the ILD as the leader of the Scottsboro legal defense. Eventually, the ILD would become a junior partner in a third organization, a liberal coalition called the Scottsboro Defense Committee (SDC).

In January of 1935, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to review the third convictions of Patterson and Norris. Three months later, the court once again overturned the guilty verdicts and ordered new trials, ruling in Patterson v. Alabama and Norris v. Alabama that the defendants were denied a fair trial because African Americans had been systematically excluded from Jackson County jury rolls. The landmark decision paved the way for the integration of juries across the nation.

Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center

Patterson was convicted of rape for a fourth time in January 1936, but this time his sentence was set at 75 years in prison. Following the verdict, another of the defendants, Ozie Powell, was shot in the head after attacking a deputy sheriff in an apparent escape attempt. After Patterson’s conviction was upheld in the Alabama Supreme Court, the prosecution and the Scottsboro Defense Committee agreed to a strange compromise in an effort to end the long ordeal. Clarence Norris was convicted of rape and sentenced to death; Norris’ sentence was subsequently commuted to life imprisonment by Alabama governor Bibb Graves. Andy Wright and Charlie Weems also were convicted of rape and sentenced to lengthy prison terms. Rape charges were dropped against Powell, but he was convicted of assaulting the deputy sheriff and sentenced to 20 years. Meanwhile, all charges against the other four defendants—Roy Wright, Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson, and Eugene Williams—were dropped. Thus, on the basis of the same body of evidence, four defendants were freed and four convicted. In 1938, a final attempt to win the remaining prisoners’ freedom failed when both the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles and Governor Graves denied pardon applications. Charlie Weems was paroled in 1943; Clarence Norris and Andy Wright were paroled a year later but both were sent back to prison shortly thereafter for violating the terms of their probation; Ozie Powell was paroled in 1946; Haywood Patterson escaped from prison in 1948. Norris, the last surviving defendant, was finally pardoned in 1976. On April 19, 2013, Alabama governor Robert Bentley signed historic legislation exonerating the nine men of all guilt in the case at the Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center in Scottsboro. Clarence Norris Jr. was in attendance. On November 21, 2013, the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles voted unanimously to pardon Haywood Patterson, Charlie Weems, and Andy Wright, the last of the accused to still have convictions in their records.

Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center

Patterson was convicted of rape for a fourth time in January 1936, but this time his sentence was set at 75 years in prison. Following the verdict, another of the defendants, Ozie Powell, was shot in the head after attacking a deputy sheriff in an apparent escape attempt. After Patterson’s conviction was upheld in the Alabama Supreme Court, the prosecution and the Scottsboro Defense Committee agreed to a strange compromise in an effort to end the long ordeal. Clarence Norris was convicted of rape and sentenced to death; Norris’ sentence was subsequently commuted to life imprisonment by Alabama governor Bibb Graves. Andy Wright and Charlie Weems also were convicted of rape and sentenced to lengthy prison terms. Rape charges were dropped against Powell, but he was convicted of assaulting the deputy sheriff and sentenced to 20 years. Meanwhile, all charges against the other four defendants—Roy Wright, Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson, and Eugene Williams—were dropped. Thus, on the basis of the same body of evidence, four defendants were freed and four convicted. In 1938, a final attempt to win the remaining prisoners’ freedom failed when both the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles and Governor Graves denied pardon applications. Charlie Weems was paroled in 1943; Clarence Norris and Andy Wright were paroled a year later but both were sent back to prison shortly thereafter for violating the terms of their probation; Ozie Powell was paroled in 1946; Haywood Patterson escaped from prison in 1948. Norris, the last surviving defendant, was finally pardoned in 1976. On April 19, 2013, Alabama governor Robert Bentley signed historic legislation exonerating the nine men of all guilt in the case at the Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center in Scottsboro. Clarence Norris Jr. was in attendance. On November 21, 2013, the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles voted unanimously to pardon Haywood Patterson, Charlie Weems, and Andy Wright, the last of the accused to still have convictions in their records.

In human terms, the Scottsboro trials were an unmitigated tragedy. The defendants’ lives were shattered by the long legal battle and the horrific conditions in the Alabama prison system. Most of the so-called Scottsboro Boys struggled to adapt to life as free men. In legal terms, the case was likewise a gross miscarriage of justice, despite the important precedents established by the U.S. Supreme Court. As a political and social movement and a cultural symbol, however, the Scottsboro case played an immeasurable part in undermining the structures of white supremacy in Alabama, the South, and throughout the nation.Carter, Dan T. Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984.Carter, Dan T. Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984.

Further Reading

- Acker, James R. Scottsboro and Its Legacy: The Cases that Challenged American Legal and Social Justice. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2008.

- Anker, Daniel, et al. “Scottsboro: An American Tragedy.” DVD. The American Experience. Alexandria, Va.: PBS Home Video, 2005.

- Carter, Dan T. Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984.

- Goodman, James. Stories of Scottsboro. New York: Pantheon Books, 1994.

- Kelley, Robin D. G. “Scottsboro Case,” in Buhle, Mari Jo, Paul Buhle, Dan Georgakas, eds. Encyclopedia of the American Left. New York: Garland Publishing, 1990.

- Norris, Clarence, and Sybil D. Washington. The Last of the Scottsboro Boys. New York: Putnam, 1978.

- Patterson, Haywood, and Earl Conrad. Scottsboro Boy. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1950.