Freedmen's Bureau in Alabama

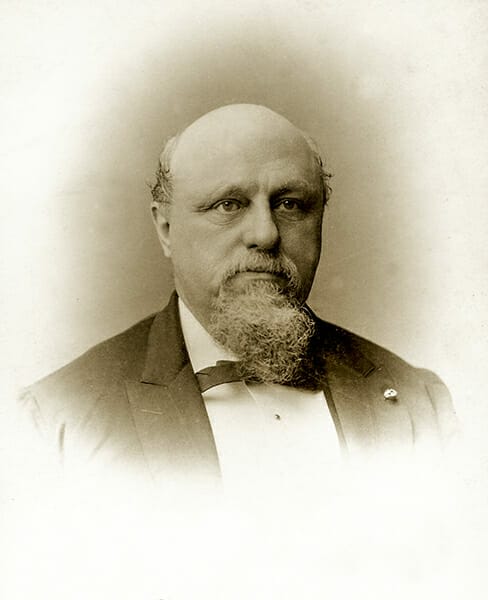

Wager Swayne

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (commonly referred to as the Freedmen’s Bureau) was established by an act of Congress on March 3, 1865, to provide relief services for emancipated blacks and refugees in Alabama and other former Confederate states who were displaced in the aftermath of the Civil War. Under the direction of Brig. Gen. Wager Swayne of the Union Army, the bureau’s many functions included helping Alabama’s 439,000 freedpeople find employment, but it also established hospitals and schools, provided food and clothing, and supervised labor contracts between freedmen and planters. In addition, Swayne and other bureau officials tried to influence lawmakers to pass measures to improve the lives of former slaves and to register them to vote. Historians conclude that the bureau was successful in its relief and education efforts, including providing adequate healthcare, but it did not succeed in dealing with the labor problems that arose after the war, as racism hindered not only efforts to guarantee the rights of freedpeople and but also attempts to improve their economic status.

Wager Swayne

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (commonly referred to as the Freedmen’s Bureau) was established by an act of Congress on March 3, 1865, to provide relief services for emancipated blacks and refugees in Alabama and other former Confederate states who were displaced in the aftermath of the Civil War. Under the direction of Brig. Gen. Wager Swayne of the Union Army, the bureau’s many functions included helping Alabama’s 439,000 freedpeople find employment, but it also established hospitals and schools, provided food and clothing, and supervised labor contracts between freedmen and planters. In addition, Swayne and other bureau officials tried to influence lawmakers to pass measures to improve the lives of former slaves and to register them to vote. Historians conclude that the bureau was successful in its relief and education efforts, including providing adequate healthcare, but it did not succeed in dealing with the labor problems that arose after the war, as racism hindered not only efforts to guarantee the rights of freedpeople and but also attempts to improve their economic status.

Swayne, who arrived in Alabama in July 1865, oversaw the bureau as assistant commissioner. The bureau was headquartered in Washington, D.C., with local offices in all former slave states, except Delaware. Assistant commissioners oversaw operations in the states with the help of various staff officers, who, in Alabama, were located in 12 field offices throughout the state. A Union veteran from Ohio, Swayne had previously participated in many of the war’s campaigns. Economic and political circumstances in Alabama after the war led many residents to obtain help from the bureau. Poor weather conditions and insect pests led to crop failures through 1868. In response, the bureau issued full food rations to blacks and whites, Unionist and Confederate, and half rations to children under 14. In June 1866, for example, nearly 800,000 rations were issued to more than 33,000 Alabamians, the majority of whom were white, because of crop failures in that year and the previous year. Other relief organizations from outside the state, such as the National Freedmen’s Relief Association, also provided food and clothing to African Americans. By the end of 1868, the bureau had closed down its food relief operations, however.

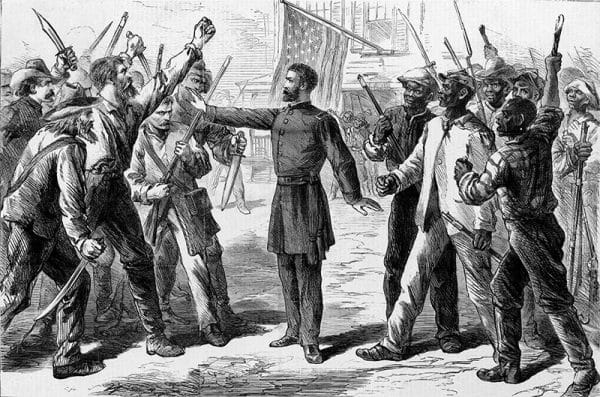

Freedmen’s Bureau Engraving

After slavery was abolished, Swayne and other state commissioners implemented a new labor system to maintain agricultural production. Emancipated blacks and planters entered into contracts, which, if for one month or more, were in written form and required approval from a bureau employee. Swayne hoped that blacks would be willing to return as laborers to the plantations. Those who did not would face arrest or be sent to work at the bureau-run home colonies. The bureau helped freedpeople negotiate and approve contracts as well as handled violations by employees and employers. It also forced healthy former slaves to work, or threatened them with vagrancy charges. The bureau also trained some African Americans whom it had confined to the colonies and helped them secure employment.

Freedmen’s Bureau Engraving

After slavery was abolished, Swayne and other state commissioners implemented a new labor system to maintain agricultural production. Emancipated blacks and planters entered into contracts, which, if for one month or more, were in written form and required approval from a bureau employee. Swayne hoped that blacks would be willing to return as laborers to the plantations. Those who did not would face arrest or be sent to work at the bureau-run home colonies. The bureau helped freedpeople negotiate and approve contracts as well as handled violations by employees and employers. It also forced healthy former slaves to work, or threatened them with vagrancy charges. The bureau also trained some African Americans whom it had confined to the colonies and helped them secure employment.

The bureau also attempted to provide freed blacks with an education. Swayne ordered subordinates to locate buildings, whether abandoned or controlled by the federal government, that could be used as schools. Owing to a lack of funds, the bureau accepted assistance from northern benevolent societies, which contributed resources to pay teachers and purchase books and members to instruct the freedmen. In northern Alabama, for instance, the Pittsburgh Freedmen’s Aid Society supported nearly a dozen schools in Huntsville and Athens, and a similar society provided assistance to schools in Montgomery and Mobile.

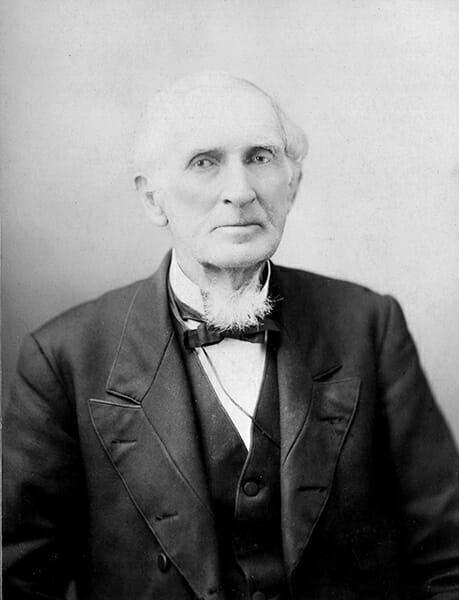

Robert M. Patton

The program initially seemed to make progress in educating freed blacks, but it was not without its problems. The number of students increased from 3,100 in October 1866 to nearly 10,000 by June 1867. Many southern whites supported education for freed blacks. They believed that they, not northern missionaries, should oversee black education and many wanted to prevent African Americans from obtaining equal social and political rights as well. Alabama governor Robert M. Patton told the state legislature that it was necessary to control the schools in order to maintain white supremacy, and some whites relied upon violence and intimidation to achieve that goal. In early 1866, at least three churches holding classes were subject to arson attacks and vandals destroyed school furniture in Greenville. Two years later, a school in Randolph County was completely burned. In addition, some whites refused to house northern instructors, and bureaucratic problems, such as staff turnover and lack of knowledge about teachers’ salaries, contributed to the confusion in operating this plan. By the middle of 1868, the bureau stopped paying teachers, and schools declined until the total number of students in 1870 was 2,100, as compared with 10,000 students during the 1866-1867 school year.

Robert M. Patton

The program initially seemed to make progress in educating freed blacks, but it was not without its problems. The number of students increased from 3,100 in October 1866 to nearly 10,000 by June 1867. Many southern whites supported education for freed blacks. They believed that they, not northern missionaries, should oversee black education and many wanted to prevent African Americans from obtaining equal social and political rights as well. Alabama governor Robert M. Patton told the state legislature that it was necessary to control the schools in order to maintain white supremacy, and some whites relied upon violence and intimidation to achieve that goal. In early 1866, at least three churches holding classes were subject to arson attacks and vandals destroyed school furniture in Greenville. Two years later, a school in Randolph County was completely burned. In addition, some whites refused to house northern instructors, and bureaucratic problems, such as staff turnover and lack of knowledge about teachers’ salaries, contributed to the confusion in operating this plan. By the middle of 1868, the bureau stopped paying teachers, and schools declined until the total number of students in 1870 was 2,100, as compared with 10,000 students during the 1866-1867 school year.

The bureau also established a health department through which many black Alabamians received medical assistance from 1865 until early 1869. Swayne believed that local civil authorities should actively participate in the care of its needy citizens, both white and black. Civil officials, however, thought that local governments should assist whites and that the bureau should care for members of the black community. The bureau assisted freed blacks who suffered from tuberculosis, yellow fever, and smallpox in general hospitals, smallpox hospitals, and in home colonies, whose purpose was to provide food and shelter to the needy. The latter facilities often housed some aged and infirm blacks and provided temporary shelter for those seeking employment. Facilities that supplied medical care in addition to food and clothing offered a variety of services from practicing physicians. The bureau organized a home colony at Garland in Butler County as a hospital that operated for about a year and a half in 1867 and 1868. After the bureau issued orders in September 1867 for the closing of its hospitals and colonies in Alabama, local officials in Butler County refused to operate the facility. Overall though, the bureau helped provide medical services to more than 17,000 individuals and at least made some effort to alleviate their suffering.

The Freedmen’s Bureau operated in Alabama for five years, ending operations in 1870. During its tenure, the bureau did provide educational opportunities as well as food, clothing, and shelter to whites and blacks. The bureau could not solve all the problems generated in the aftermath of the Civil War, and it had its own internal complications as well. The larger problem of racism contributed to its difficulties in trying to help freedmen adjust to their new freedoms.

Additional Resources

Bethel, Elizabeth. “The Freedmen’s Bureau in Alabama.” The Journal of Southern History 14 (February 1948): 49-92.

Fitzgerald, Michael W. “Emancipation and Military Pacification: The Freedmen’s Bureau and Social Control in Alabama.” In The Freedmen’s Bureau and Reconstruction: Reconsiderations. Paul A. Cimbala and Randall M. Miller, eds. New York: Fordham University Press, 1999.

———. “Wager Swayne, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the Politics of Reconstruction in Alabama.” Alabama Review 48 (July 1995): 188-218.

Hasson, Gail S. “Health and Welfare of Freedmen in Reconstruction Alabama.” Alabama Review 35 (April 1982): 94-110.

White, Kenneth B. “Wager Swayne: Racist or Realist?” Alabama Review 31 (April 1978) : 92-109.