Black Heritage Council

Shiloh-Rosenwald School in Notasulga

The Black Heritage Council (BHC) was established in 1984 as an advisory body to the Alabama Historical Commission (AHC) and is the first such council connected with a state historic preservation office in the United States. Most notably, the BHC has participated in several high-profile state preservation projects, including the Selma to Montgomery National Voting Rights Historic Trail in 1996, the documentation of Rosenwald Schools in 2001, and the 2019 discovery of the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to arrive in the United States. The BHC works to add sites to AHC’s Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage and the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) and affiliated sites and to have historical markers erected on sites of historical importance in the state.

Shiloh-Rosenwald School in Notasulga

The Black Heritage Council (BHC) was established in 1984 as an advisory body to the Alabama Historical Commission (AHC) and is the first such council connected with a state historic preservation office in the United States. Most notably, the BHC has participated in several high-profile state preservation projects, including the Selma to Montgomery National Voting Rights Historic Trail in 1996, the documentation of Rosenwald Schools in 2001, and the 2019 discovery of the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to arrive in the United States. The BHC works to add sites to AHC’s Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage and the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) and affiliated sites and to have historical markers erected on sites of historical importance in the state.

The council consists of 18 members. It includes one member from each of the seven congressional districts in Alabama; three members-at-large; three representatives of collegiate community institutions, with one representing a two-year Historically Black College and University (HBCU) and the other representing a four-year HBCU; three members from statewide cultural and historical institutions; one ex-officio representative of the historical commission; and a chair person. The council is supported by a 25-member board of volunteers.

The 1966 National Historic Preservation Act led to the creation of the AHC in August 1966 and local preservation organization Landmarks Foundation of Montgomery in May 1968. But it was not until the mid-1970s that these organizations began working with Black communities in Alabama to preserve their historic structures. Similarly, the Alabama State Teachers Association (1882-1969) had promoted the teaching of Black history and the Alabama Center for Higher Education (1967-late 1980s) held conferences in the 1970s to train and foster communication among librarians, archivists, and museum curators nationwide regarding methods of preserving and0 providing access to primary sources regarding black history.

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

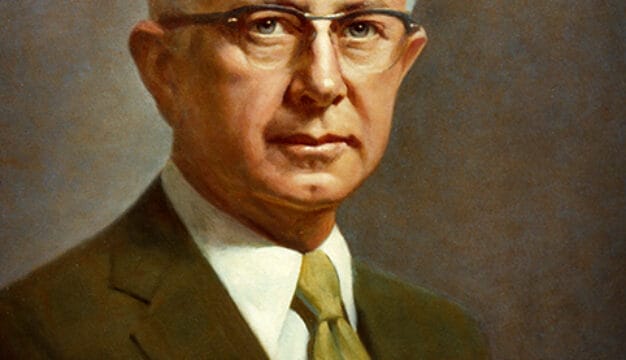

The first director of the AHC, W. Warner Floyd, and the third director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History (ADAH), Milo Howard, assisted Tuskegee University president Luther H. Foster and George Washington Carver Museum curator Bess Bolden Walcott secure the recognition of the Tuskegee Institute as a National Historic Site in 1974. Floyd, Howard, and U.S. senator John Sparkman worked with the Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation and the National Park Service to place Montgomery‘s Dexter Avenue King Baptist Church on the NHRP in July 1974. In addition, Floyd and Howard helped add the St. Louis Missionary Baptist Church of Mobile to the NRHP in October 1976. By the late 1970s, the AHC, ADAH, and the Landmarks Foundation of Montgomery were working with Black historic preservationists including Richard Bailey, Joseph Caver, Marie Coone, Zelia Evans, and Frances Smiley.

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

The first director of the AHC, W. Warner Floyd, and the third director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History (ADAH), Milo Howard, assisted Tuskegee University president Luther H. Foster and George Washington Carver Museum curator Bess Bolden Walcott secure the recognition of the Tuskegee Institute as a National Historic Site in 1974. Floyd, Howard, and U.S. senator John Sparkman worked with the Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation and the National Park Service to place Montgomery‘s Dexter Avenue King Baptist Church on the NHRP in July 1974. In addition, Floyd and Howard helped add the St. Louis Missionary Baptist Church of Mobile to the NRHP in October 1976. By the late 1970s, the AHC, ADAH, and the Landmarks Foundation of Montgomery were working with Black historic preservationists including Richard Bailey, Joseph Caver, Marie Coone, Zelia Evans, and Frances Smiley.

The second AHC director, F. Lawrence Oaks, and the AHC’s NRHP Coordinator at that time, Ellen Mertins, helped Selma educator and civic leader Louretta Wimberly apply to place the First Colored Baptist Church of Selma on the NRHP in 1979 after the church was partially destroyed in a May 1978 tornado, prompting restoration efforts. A local freedman had established the church for enslaved persons in 1845, and it housed the first school for Selma’s black youth and during the civil rights era notably served as a “Movement Church” in 1963 by hosting the Dallas County Voters League and the local Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee.

Phillips Memorial Auditorium

The Black Heritage Council Task Force was established during the 16th annual AHC preservation conference in Montgomery on June 17, 1983, to create a statewide black historic preservation committee that would consult for the AHC. Members included George Boyd of Miles College, Idella Childs who helped preserve the Lincoln Normal School in Marion, Richard Dozier who served as chair of Tuskegee University’s Department of Architecture, Zelia Evans who led the Black Culture Preservation Committee of the Landmarks Foundation, and Louretta Wimberly. Dozier was selected as the first chair in January 1984, and led the development of a slideshow entitled Preserving Alabama’s Historic Black Resources: Where Do We Go From Here? Under Shirley Qualls’s leadership as the second chair, the council produced a calendar of African American churches entitled “Keepers of the Faith” in 1988 and collaborated with Frances Smiley of the Alabama Tourism Department to expand a brochure entitled “Alabama’s Black Heritage: A Tour of Historic Sites” that was originally developed in 1983. In 1992, the council produced the “Alabama’s Historic Black Colleges” poster including archival photographs and historical sketches of 11 Alabama HBCUs.

Phillips Memorial Auditorium

The Black Heritage Council Task Force was established during the 16th annual AHC preservation conference in Montgomery on June 17, 1983, to create a statewide black historic preservation committee that would consult for the AHC. Members included George Boyd of Miles College, Idella Childs who helped preserve the Lincoln Normal School in Marion, Richard Dozier who served as chair of Tuskegee University’s Department of Architecture, Zelia Evans who led the Black Culture Preservation Committee of the Landmarks Foundation, and Louretta Wimberly. Dozier was selected as the first chair in January 1984, and led the development of a slideshow entitled Preserving Alabama’s Historic Black Resources: Where Do We Go From Here? Under Shirley Qualls’s leadership as the second chair, the council produced a calendar of African American churches entitled “Keepers of the Faith” in 1988 and collaborated with Frances Smiley of the Alabama Tourism Department to expand a brochure entitled “Alabama’s Black Heritage: A Tour of Historic Sites” that was originally developed in 1983. In 1992, the council produced the “Alabama’s Historic Black Colleges” poster including archival photographs and historical sketches of 11 Alabama HBCUs.

Freedom Rides Museum

By mid-1994, the BHC had held a “Building a Black Heritage Network” meeting in Birmingham to develop a network of people beyond the BHC who were interested and involved in preserving the state’s African American historic buildings and archaeological sites. (Annual workshops continue at various historic sites around the state to discuss local preservation issues.) Also around this time, preservationists in Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and South Carolina were consulting with the BHC to develop similar organizations. And in 1999, the BHC participated in the first Southeast Regional African American Preservation Alliance conference in Birmingham. Later, the BHC helped establish the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail along US Highway 80 with the assistance of U.S. representative John Lewis in May 1996. In 2001, Dorothy Walker began a program to preserve Black schools constructed by the Julius Rosenwald Fund from 1917 to 1948 and Equalization Schools constructed in the 1950s. Walker later became director of the Freedom Rides Museum, which opened in the former Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station in May 2011.

Freedom Rides Museum

By mid-1994, the BHC had held a “Building a Black Heritage Network” meeting in Birmingham to develop a network of people beyond the BHC who were interested and involved in preserving the state’s African American historic buildings and archaeological sites. (Annual workshops continue at various historic sites around the state to discuss local preservation issues.) Also around this time, preservationists in Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and South Carolina were consulting with the BHC to develop similar organizations. And in 1999, the BHC participated in the first Southeast Regional African American Preservation Alliance conference in Birmingham. Later, the BHC helped establish the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail along US Highway 80 with the assistance of U.S. representative John Lewis in May 1996. In 2001, Dorothy Walker began a program to preserve Black schools constructed by the Julius Rosenwald Fund from 1917 to 1948 and Equalization Schools constructed in the 1950s. Walker later became director of the Freedom Rides Museum, which opened in the former Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station in May 2011.

In April 2019, BHC chair Frazine Taylor was elected as the first black president of the Alabama Historical Association. The following May, the BHC collaborated with the AHC, the National Geographic Society, SEARCH (an archaeological and cultural resource management firm), the Smithsonian Institution, and other agencies to recover the Clotilda; the last known vessel to bring enslaved people to the United States, in July 1860. As of 2022, Tuskegee attorney Lateefah Muhammad was serving as chair of the BHC.