Fort Morgan Museum and State Historic Site

Fort Morgan Museum

Fort Morgan Museum and State Historic Site, located on Mobile Point, Baldwin County, has been the location of two fortifications that have been occupied in six separate conflicts. With the current museum opening to the public in 1967, the site has been owned and operated by the Alabama Historical Commission (AHC) since 1977 and is an educational tourist destination. The museum presents artifacts and memorabilia from the American Civil War and World Wars I and II, as well as nearby lighthouses. The fort was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1961.

Fort Morgan Museum

Fort Morgan Museum and State Historic Site, located on Mobile Point, Baldwin County, has been the location of two fortifications that have been occupied in six separate conflicts. With the current museum opening to the public in 1967, the site has been owned and operated by the Alabama Historical Commission (AHC) since 1977 and is an educational tourist destination. The museum presents artifacts and memorabilia from the American Civil War and World Wars I and II, as well as nearby lighthouses. The fort was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1961.

Early History

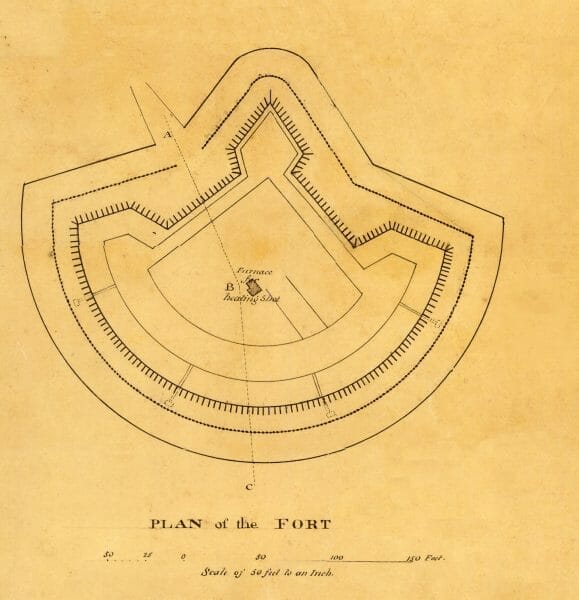

Fort Bowyer Diagram

In 1778, the first military defense of Mobile Point was a temporary gun battery used by Bernardo de Gálvez‘s Spanish forces in their campaign for Mobile. The first fort to stand on Mobile Point was a fan-shaped sand and log structure that saw action in the War of 1812. Known as Fort Bowyer, the fortification fell into British hands on February 12, 1815, following negotiations on February 11. In the aftermath, the federal government decided more substantial works were needed to protect the coastal areas and devised the “Third System” fortifications for coastal defense. The U.S. Corps of Engineers was initially intended to have minimum oversight of the fort’s construction, but after two failed attempts to commission the work to civilian contractors, the responsibility was fully placed upon them. Simon Bernard, a French military engineer who had served under Napoleon before working with the United States, designed what was initially known as the “Work on Mobile Point.” Construction spanned from 1819-34, stalling several times. When finished, the fort was a brick masonry structure of pentagonal design with five bastions and a decagon shaped citadel for soldiers’ quarters inside. The fort was named for Revolutionary War hero Daniel Morgan in 1833.

Fort Bowyer Diagram

In 1778, the first military defense of Mobile Point was a temporary gun battery used by Bernardo de Gálvez‘s Spanish forces in their campaign for Mobile. The first fort to stand on Mobile Point was a fan-shaped sand and log structure that saw action in the War of 1812. Known as Fort Bowyer, the fortification fell into British hands on February 12, 1815, following negotiations on February 11. In the aftermath, the federal government decided more substantial works were needed to protect the coastal areas and devised the “Third System” fortifications for coastal defense. The U.S. Corps of Engineers was initially intended to have minimum oversight of the fort’s construction, but after two failed attempts to commission the work to civilian contractors, the responsibility was fully placed upon them. Simon Bernard, a French military engineer who had served under Napoleon before working with the United States, designed what was initially known as the “Work on Mobile Point.” Construction spanned from 1819-34, stalling several times. When finished, the fort was a brick masonry structure of pentagonal design with five bastions and a decagon shaped citadel for soldiers’ quarters inside. The fort was named for Revolutionary War hero Daniel Morgan in 1833.

Ruins of Fort Morgan Citadel

The federal government held Fort Morgan with a small caretaker’s force until January 4, 1861, when the state of Alabama seized the fortification. The Battle of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864, was followed by the Siege of Fort Morgan by federal naval and land forces, which ended on August 22. Confederate general Richard L. Page surrendered Fort Morgan on August 23 after shelling from U.S. forces caused a fire in the citadel inside the fort. This fire led to the disposal of gunpowder in the fort’s cisterns to avoid explosion, which left the fort with little ammunition and no source of water. Following the surrender, members of the U.S. Army, including those from the United States Colored Troops (USCT), held the fort for the remainder of the war until their departure in 1868.

Ruins of Fort Morgan Citadel

The federal government held Fort Morgan with a small caretaker’s force until January 4, 1861, when the state of Alabama seized the fortification. The Battle of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864, was followed by the Siege of Fort Morgan by federal naval and land forces, which ended on August 22. Confederate general Richard L. Page surrendered Fort Morgan on August 23 after shelling from U.S. forces caused a fire in the citadel inside the fort. This fire led to the disposal of gunpowder in the fort’s cisterns to avoid explosion, which left the fort with little ammunition and no source of water. Following the surrender, members of the U.S. Army, including those from the United States Colored Troops (USCT), held the fort for the remainder of the war until their departure in 1868.

Fort Morgan Hospital

In an attempt to update the Fort Morgan post for use in future defense, the federal government began constructing concrete gun emplacements, beginning with Battery Bowyer in 1895. Bowyer was manned for possible hostilities during the Spanish American War, but the conflict ended too quickly for the war to reach Mobile Bay. Battery Dearborn was completed in 1900, with Battery Duportail being constructed inside the existing masonry fort. Batteries Thomas and Schenck were also completed during this period and located near the fort. In addition to these batteries, an entire complex of buildings, including an ice, lighting, and pumping plant, hospital, bakery, and living quarters, were constructed between 1898-1908. The post was manned but fired no defensive shots in World War I or World War II.

Fort Morgan Hospital

In an attempt to update the Fort Morgan post for use in future defense, the federal government began constructing concrete gun emplacements, beginning with Battery Bowyer in 1895. Bowyer was manned for possible hostilities during the Spanish American War, but the conflict ended too quickly for the war to reach Mobile Bay. Battery Dearborn was completed in 1900, with Battery Duportail being constructed inside the existing masonry fort. Batteries Thomas and Schenck were also completed during this period and located near the fort. In addition to these batteries, an entire complex of buildings, including an ice, lighting, and pumping plant, hospital, bakery, and living quarters, were constructed between 1898-1908. The post was manned but fired no defensive shots in World War I or World War II.

Deactivation and Museum Development

The fort had been deactivated by the U.S. government and turned over to the state of Alabama in 1922. By the late 1930s, discussions on how to use the property centered around turning the fort into an outdoor artillery park that would be called the “Fort Morgan Museum of Guns.” In 1941, the fort was reactivated for military use in World War II, pausing plans for developing the historic site and museum until the war ended.

An act of the State Legislature created the Fort Morgan Historical Commission in 1955, continuing preservation efforts for the site. In 1959, the Foley Woman’s Club began a new initiative to establish a museum at Fort Morgan. Plans included the use of the 125-foot-long “ammunition building” located on the property. Referred to in modern park interpretation as the “Peace Magazine,” the building was originally designed to store ammunition during peace time, acting as a safety measure to ensure that if an explosion occurred it would not threaten any of the artillery platforms.

Battery Duportail Support System

By 1963, a shortfall in state funding led the museum to be housed in a room of Battery Duportail, a part of the concrete battery system that had been built inside and surrounding the fort in the late nineteenth century. Although the room already featured electrical wiring, air conditioning, and central heating, the location was plagued by poor drainage and lack of space. By the fall of 1963, the Fort Morgan Historical Commission began considering options for adding another room of the battery to the museum.

Battery Duportail Support System

By 1963, a shortfall in state funding led the museum to be housed in a room of Battery Duportail, a part of the concrete battery system that had been built inside and surrounding the fort in the late nineteenth century. Although the room already featured electrical wiring, air conditioning, and central heating, the location was plagued by poor drainage and lack of space. By the fall of 1963, the Fort Morgan Historical Commission began considering options for adding another room of the battery to the museum.

Some of the first objects displayed in the museum were a collection of photos taken at Fort Morgan before and after the Battle of Mobile Bay. These served as the focus for the first phase of interpretation implemented in 1963 and have continued to be a staple of the interpretive plan since that time. Six cases displayed a collection of 200 artifacts purchased from a collector in Vicksburg, Mississippi. The collection included Confederate money, a sausage grinder, firearms, pistols, buckles, a courier’s pouch, and a lady’s side saddle. These items have no discernable provenance to the site but served as a secondary attraction to the few items from Fort Morgan. Fort-related items included several construction plans of the fort, a map of Gen. Gordon Granger’s siege operations in 1864, and a copy of John C. Abbott’s History of the Civil War in America.

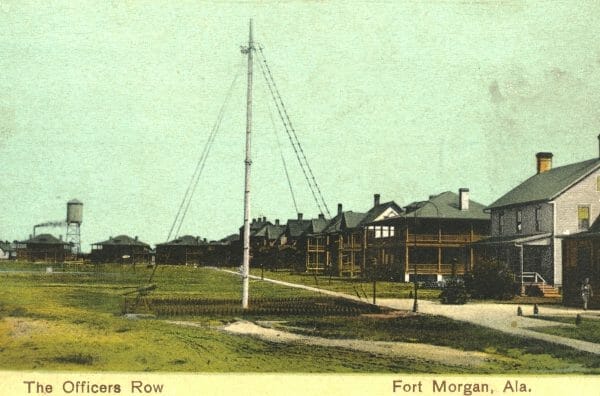

Officer’s Row, 1915

By 1966, $40,000 (more than $320,000 in modern dollars) had been allocated by the state for the construction of a museum building outside the fort, with a scheduled opening for the summer of 1967. The ten-sided facility was designed to be reminiscent of the citadel that had occupied the interior of the fort prior to the Siege of Fort Morgan during the Civil War. Control of the site was officially transferred to the Alabama Historical Commission in 1977. In 1978, the AHC re-designated the Fort Morgan Museum as the James B. Allen Memorial Museum. Allen had served as a state senator, lieutenant governor, and U.S. senator prior to his sudden death while on vacation at Gulf Shores in June 1978. The museum was named in recognition of Allen’s “contributing and continued interest” in the facility.

Officer’s Row, 1915

By 1966, $40,000 (more than $320,000 in modern dollars) had been allocated by the state for the construction of a museum building outside the fort, with a scheduled opening for the summer of 1967. The ten-sided facility was designed to be reminiscent of the citadel that had occupied the interior of the fort prior to the Siege of Fort Morgan during the Civil War. Control of the site was officially transferred to the Alabama Historical Commission in 1977. In 1978, the AHC re-designated the Fort Morgan Museum as the James B. Allen Memorial Museum. Allen had served as a state senator, lieutenant governor, and U.S. senator prior to his sudden death while on vacation at Gulf Shores in June 1978. The museum was named in recognition of Allen’s “contributing and continued interest” in the facility.

With the new building came a new era in interpretation. A case featuring a bayonet, bullets, and a bottle neck found at the fort, along with cannon balls and grapeshot removed from various excavations at the site joined existing displays of artifacts. Later additions included fragments of the cannon that exploded and killed Confederate colonel Charles S. Stewart, a federal soldier’s canteen found at nearby Fort Blakeley, and a Confederate iron pot found at Spanish Fort. Collections also include World War I and World War II uniforms and artifacts from the fort’s occupation during each period, along with copies of the YMCA publication for the men stationed at Fort Morgan entitled “Home Ties.” A display of Native American artifacts was added to document the history of the indigenous inhabitants of the area and included projectile points and pottery.

Lighthouse Lens Exhibit

Lighthouses are a central aspect of the museum and site interpretation. One of the most prominent artifacts to be installed was the lens from nearby Sand Island lighthouse. The exhibit showcases the Fresnel lens donated by the U.S. Coast Guard and details its unique technology and the history of the lighthouse service on Mobile Point. The first Mobile Point lighthouse was a brick structure built in 1822 that was heavily damaged in the Battle of Mobile Bay. A temporary wooden replacement was followed by an iron tower in 1872. A taller structure replaced this in 1966. That tower was removed by the AHC in 2004, with the lens itself currently part of the museum’s interpretation. The nearby Sand Island lighthouse remains visible in the Gulf of Mexico when looking south from atop the fort’s walls.

Lighthouse Lens Exhibit

Lighthouses are a central aspect of the museum and site interpretation. One of the most prominent artifacts to be installed was the lens from nearby Sand Island lighthouse. The exhibit showcases the Fresnel lens donated by the U.S. Coast Guard and details its unique technology and the history of the lighthouse service on Mobile Point. The first Mobile Point lighthouse was a brick structure built in 1822 that was heavily damaged in the Battle of Mobile Bay. A temporary wooden replacement was followed by an iron tower in 1872. A taller structure replaced this in 1966. That tower was removed by the AHC in 2004, with the lens itself currently part of the museum’s interpretation. The nearby Sand Island lighthouse remains visible in the Gulf of Mexico when looking south from atop the fort’s walls.

The interior of the fort features a series of casemates—vaulted, bomb-proof rooms that are built into the inner walls of the fort. Three casemates have been recreated to interpret the lives of soldiers and laundresses, as well as to provide a look at a quartermaster’s station. Battery Duportail, the concrete structure on the south side of the fort’s interior, was completed in the early twentieth century and designed to operate two modern coastal defense guns, often referred to as 12-inch guns due to the gun caliber and as “disappearing rifles” because the mechanized carriages could withdraw the gun from sight.

Architectural Features

Fort Morgan

As one enters the site there are several structures remaining of the old post, dating from 1898-1917. To the right, near the Mobile Bay ferry landing, is the medical first sergeant’s quarters that housed the senior medical non-commissioned officer on post and is the only remaining structure from the medical complex and hospital. To the left, near the site entrance, are three structures: the Senior Officers’ Quarters, the detached kitchen for another Officers’ Quarters, and the old post Administration building. Just inside the gate is a reconstructed 1860s U.S. Army mortar battery. The old Post Bakery lies further back between the main road and Battery Dearborn. Dotting the property in numerous places are several large, round concrete cisterns that once formed the water supply for the site. The foundations for much of the old post can be seen by walking the brick paths from the museum towards the Post Administration buildings. A commemorative area near the museum is dedicated to Fort Bowyer and lies off the walking path of the Engineer’s Wharf, heading to the Mobile Bay beach. At the northwest corner of the fort are two concrete batteries, Battery Schenck and Battery Thomas, both of which were platforms for smaller, rapid-fire weapons designed to stop enemy landing craft.

Fort Morgan

As one enters the site there are several structures remaining of the old post, dating from 1898-1917. To the right, near the Mobile Bay ferry landing, is the medical first sergeant’s quarters that housed the senior medical non-commissioned officer on post and is the only remaining structure from the medical complex and hospital. To the left, near the site entrance, are three structures: the Senior Officers’ Quarters, the detached kitchen for another Officers’ Quarters, and the old post Administration building. Just inside the gate is a reconstructed 1860s U.S. Army mortar battery. The old Post Bakery lies further back between the main road and Battery Dearborn. Dotting the property in numerous places are several large, round concrete cisterns that once formed the water supply for the site. The foundations for much of the old post can be seen by walking the brick paths from the museum towards the Post Administration buildings. A commemorative area near the museum is dedicated to Fort Bowyer and lies off the walking path of the Engineer’s Wharf, heading to the Mobile Bay beach. At the northwest corner of the fort are two concrete batteries, Battery Schenck and Battery Thomas, both of which were platforms for smaller, rapid-fire weapons designed to stop enemy landing craft.

East of the museum and fort lies an old air strip and two concrete batteries: Battery Bowyer and Battery Dearborn. The airstrip had been constructed by the state in 1960 for non-military use. Between these two batteries sits the ruins of the Peace Magazine, which was mostly destroyed by Hurricane Frederic in 1979. Recreations of the Civil War federal siege lines are located between Battery Bowyer and the fort. Over the years, hurricanes have destroyed much of the original housing on the site and caused serious damage to those structures that remain. Hurricane Sally caused particularly harsh flooding and roof damage to the Senior Officers’ house and the Bakery in 2020. The houses are used for staff housing or administrative purposes and are not open to the public.

The site and museum are open seven days a week for self-guided tours, with living history events, weapons demonstrations, and guided tours historically given each summer.

Further Reading

- England, Bob, Jack Friend, Michael Bailey, and Blanton Blankenship. Images of America: Fort Morgan. Mount Pleasant, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2000.

- Weaver, John R. A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867. McClean, Va.: Redoubt Press, 2001.