Alabama Federation of Women's Clubs

The Alabama Federation of Women’s Clubs (AFWC) was organized in Birmingham, Jefferson County, in 1895 to foster the educational interests of its members during a time when women were often denied access to higher education. It quickly widened its scope to include civic and philanthropic work and is particularly noted for its support of the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School in Birmingham. The AFWC is currently headquartered in Birmingham in Foster House, the former home of theologian Sterling Foster built in 1913. The organization was not affiliated with any political party or religious denomination, but it was generally grounded in Christian theology.

Alabama Federation of Women’s Clubs Logo

The AFWC was initially formed through the union of six women’s literary clubs: the Cadmean Circle, the Clionian Club, and the Highland Book Club of Birmingham; the No Name Club of Montgomery; the Progressive Culture Club of Decatur; and the Thursday Literary Circle of Selma. The AFWC was one of the earliest federations in the nation and the largest women’s organization in the state. It was chartered in 1907 into the General Federation of Women’s Clubs but continued to operate as the AWFC. By the 1920s, it consisted of more than 200 clubs with a total estimated 10,000 members. Some prominent early members include the first president, Mary LaFayette Robbins, noted prison and education reformer Julia Strudwick Tutwiler; Elizabeth Evans Johnston, Lura Harris Craighead, wife of progressive Mobile newspaperman Erwin Craighead; Alberta Williams Bush, wife of state legislator and railway executive Thomas Greene Bush; president and child-labor reformer Lillian Milner Orr; and social worker and chair of the Alabama Child Labor Conference Nellie Kimball Murdock.

Alabama Federation of Women’s Clubs Logo

The AFWC was initially formed through the union of six women’s literary clubs: the Cadmean Circle, the Clionian Club, and the Highland Book Club of Birmingham; the No Name Club of Montgomery; the Progressive Culture Club of Decatur; and the Thursday Literary Circle of Selma. The AFWC was one of the earliest federations in the nation and the largest women’s organization in the state. It was chartered in 1907 into the General Federation of Women’s Clubs but continued to operate as the AWFC. By the 1920s, it consisted of more than 200 clubs with a total estimated 10,000 members. Some prominent early members include the first president, Mary LaFayette Robbins, noted prison and education reformer Julia Strudwick Tutwiler; Elizabeth Evans Johnston, Lura Harris Craighead, wife of progressive Mobile newspaperman Erwin Craighead; Alberta Williams Bush, wife of state legislator and railway executive Thomas Greene Bush; president and child-labor reformer Lillian Milner Orr; and social worker and chair of the Alabama Child Labor Conference Nellie Kimball Murdock.

Only white women’s organizations were permitted to join the AFWC during the era of legal racial segregation known as Jim Crow, and its members belonged predominantly to the emerging middle and upper classes. The Alabama Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs formed separately in 1899. The two federations shared similar ideals but were often influenced by different priorities and were not affiliated with one another.

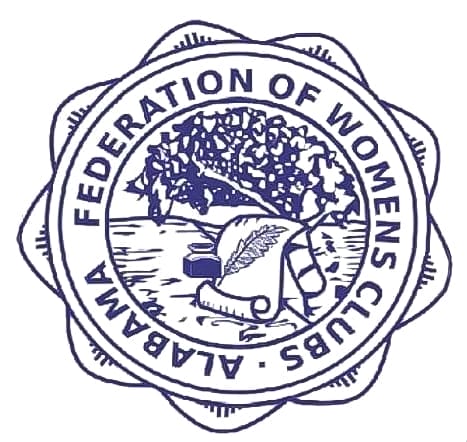

Loraine Bedsole Tunstall

Influenced by the ideals of the Progressive Era, the AFWC aimed to unite women’s clubs throughout the state to pursue civic and social reform, particularly causes that benefited women and children. Members worked to improve public and rural schools, created travelling libraries, promoted temperance, and pushed for progressive labor reforms such as an eight-hour workday, and a minimum wage for women. The AFWC advocated for training in home economics, art initiatives, the introduction of kindergartens, health reform, and the establishment of a juvenile court system. Child welfare issues were of particular importance to the AFWC because so many of the member organizations were involved in those efforts. Not only did members fight to eliminate child labor, but they also played a role in establishing the Alabama Department of Child Welfare in 1919, the predecessor to the state’s Department of Human Resources. The AFWC and other youth advocacy groups, such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the Alabama Child Labor Committee, and the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA), pressured the state legislature to create the agency. As a result, Loraine Bedsole Tunstall, a longtime child welfare activist, was appointed director of the department in 1923 and became the first woman to head a state agency in Alabama. Tunstall’s appointment led to women serving on county child welfare boards throughout the state; Alabama would be one of the first six states in the nation to create such boards.

Loraine Bedsole Tunstall

Influenced by the ideals of the Progressive Era, the AFWC aimed to unite women’s clubs throughout the state to pursue civic and social reform, particularly causes that benefited women and children. Members worked to improve public and rural schools, created travelling libraries, promoted temperance, and pushed for progressive labor reforms such as an eight-hour workday, and a minimum wage for women. The AFWC advocated for training in home economics, art initiatives, the introduction of kindergartens, health reform, and the establishment of a juvenile court system. Child welfare issues were of particular importance to the AFWC because so many of the member organizations were involved in those efforts. Not only did members fight to eliminate child labor, but they also played a role in establishing the Alabama Department of Child Welfare in 1919, the predecessor to the state’s Department of Human Resources. The AFWC and other youth advocacy groups, such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the Alabama Child Labor Committee, and the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA), pressured the state legislature to create the agency. As a result, Loraine Bedsole Tunstall, a longtime child welfare activist, was appointed director of the department in 1923 and became the first woman to head a state agency in Alabama. Tunstall’s appointment led to women serving on county child welfare boards throughout the state; Alabama would be one of the first six states in the nation to create such boards.

The AFWC raised funds for the first women’s dormitory at the University of Alabama and helped endow university scholarships. The organization was also active in historic preservation efforts and conservation of the natural environment and supported urban beautification projects. Many members were active in other organizations, such as the AESA, the Red Cross, the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC). Although individual members were active in the AESA, the AFWC did not collectively endorse women’s suffrage until 1918 because many members considered women’s suffrage too radical a topic.

Among the AFWC’s many philanthropic efforts, the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School was one of its longest running and most successful projects. It founded the institution in 1899 after charter member Elizabeth Johnston witnessed boys as young as 12 forced into the state’s convict-lease system alongside adult men in a Birmingham coal mine. In response, Johnston promoted a separate facility to house Alabama’s youthful offenders and appealed to her fellow clubwomen for help. At their request, her brother-in-law Gov. Joseph F. Johnston approved its creation, granted the school a charter, made an initial appropriation of $3,000, and appointed an all-female board of directors to administer the new institution, a first in the United States.

Alabama Boys Industrial School Band

The AFWC administered and financially supported the Boys’ School for more than 75 years. During periods when state funds were either cut significantly or completely, the AFWC financed the school through other means. The organization lobbied the state legislature to support the school’s programs, required each member club to contribute to the school, and solicited private donations to make up the rest. The Alabama Boys’ Industrial School remained under the administration of women in the AFWC as a semi-private institution until the state assumed control in 1975.

Alabama Boys Industrial School Band

The AFWC administered and financially supported the Boys’ School for more than 75 years. During periods when state funds were either cut significantly or completely, the AFWC financed the school through other means. The organization lobbied the state legislature to support the school’s programs, required each member club to contribute to the school, and solicited private donations to make up the rest. The Alabama Boys’ Industrial School remained under the administration of women in the AFWC as a semi-private institution until the state assumed control in 1975.

Today, the AFWC continues to serve the state of Alabama as an organization dedicated to community improvement through volunteer service. Members participate in projects related to the arts, education, child advocacy, and awareness and prevention of domestic violence. The organization maintains three standing committees under the umbrella of the national General Federation of Women’s Clubs: GFWC Signature Program: Domestic Violence Awareness and Prevention; GFWC Junior’s Advocate’s for Children; and AFWC President’s Project-Big Oak Ranch, a residential program for abused children.

Further Reading

- Avery, Mary Johnston. She Heard With Her Heart. Birmingham, Ala.: Press of Birmingham Publishing Company, 1944.

- Craighead, Lura Harris. History of the Alabama Federation of Women’s Clubs. 1936. Reprint, Montgomery: Paragon Press, 1968.

- Thomas, Mary Martha. The New Woman in Alabama: Social Reforms and Suffrage, 1890-1920. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1992.

- ———. Stepping Out of the Shadows: Alabama Women, 1819-1990. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.