Henry Eugene "Red" Erwin Sr.

Henry “Red” Erwin

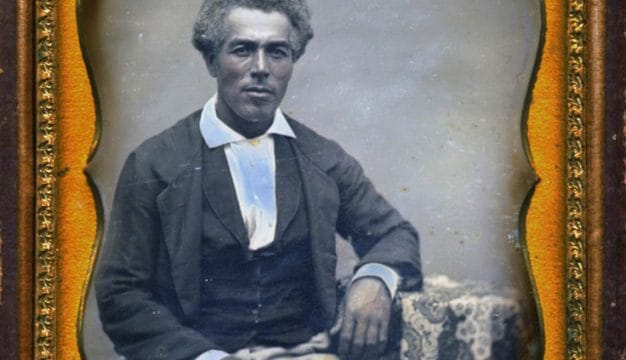

Alabama native Henry Erwin Sr. (1921-2002) earned the Medal of Honor in World War II for his actions saving the crew of his bomber that resulted in extremely painful and severe burns that disfigured him for life. Not expected to live owing to the severity of his injuries, Erwin’s medal award was expedited by the high command. Erwin did survive and became a Veterans Affairs benefits counselor in Birmingham, Jefferson County, serving in that position for many years.

Henry “Red” Erwin

Alabama native Henry Erwin Sr. (1921-2002) earned the Medal of Honor in World War II for his actions saving the crew of his bomber that resulted in extremely painful and severe burns that disfigured him for life. Not expected to live owing to the severity of his injuries, Erwin’s medal award was expedited by the high command. Erwin did survive and became a Veterans Affairs benefits counselor in Birmingham, Jefferson County, serving in that position for many years.

Erwin was born in the small hardscrabble mining town of Adamsville, Jefferson County, on May 8, 1921. The eldest child in a large family, he was raised in impoverished circumstances. His father, who is unnamed in biographical accounts, was a coal miner who died when Erwin was age 10. He then took a job in the local coal mine commissary to help his mother, Pearl Landers Erwin, support the large family. Erwin later attended high school for two years but dropped out, joining the New Deal Civilian Conservation Corps program that was instituted during the Great Depression to put young men like Erwin to work. He led a team of many other young men in similar circumstances who were planting kudzu to stop soil erosion in north Alabama. He later worked in a Birmingham steel factory.

Crew of the City of Los Angeles

In July 1942, Erwin joined the Army Reserve. In February 1943, he was called to active duty and joined the Army Air Corps. He underwent pilot training in Florida but was unable to advance out of flight school. He then received technical training in Mississippi, South Dakota, and Wisconsin, where he completed training as a radio operator and mechanic in April 1944. He was promoted to corporal that August and sergeant in October. Also that year, Erwin married Martha Elizabeth Starnes Erwin, with whom he would have a son and three daughters. He was assigned to the 52nd Bombardment Squadron, 29th Bombardment Group, Twentieth Air Force, and left for the Pacific theater in early 1945.

Crew of the City of Los Angeles

In July 1942, Erwin joined the Army Reserve. In February 1943, he was called to active duty and joined the Army Air Corps. He underwent pilot training in Florida but was unable to advance out of flight school. He then received technical training in Mississippi, South Dakota, and Wisconsin, where he completed training as a radio operator and mechanic in April 1944. He was promoted to corporal that August and sergeant in October. Also that year, Erwin married Martha Elizabeth Starnes Erwin, with whom he would have a son and three daughters. He was assigned to the 52nd Bombardment Squadron, 29th Bombardment Group, Twentieth Air Force, and left for the Pacific theater in early 1945.

Erwin served primarily as a radio operator in the Army’s newest and most advanced heavy bomber, the Boeing B-29 “Super Fortress.” It was noted for its longer range and ability to carry a higher payload of bombs compared to other U.S. bombers. By this time in the war, the B-29 was being tasked with long range missions over vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean to bomb Japan from bases on the islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian in the Marianas. He served on an aircraft known as the City of Los Angeles based at Guam, and it was his 10 fellow crewmembers who gave him the nickname “Red” for his auburn hair.

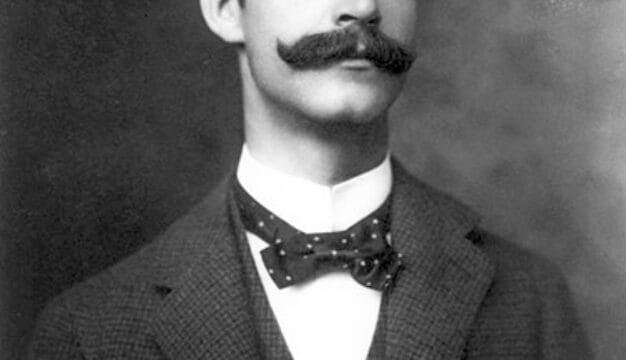

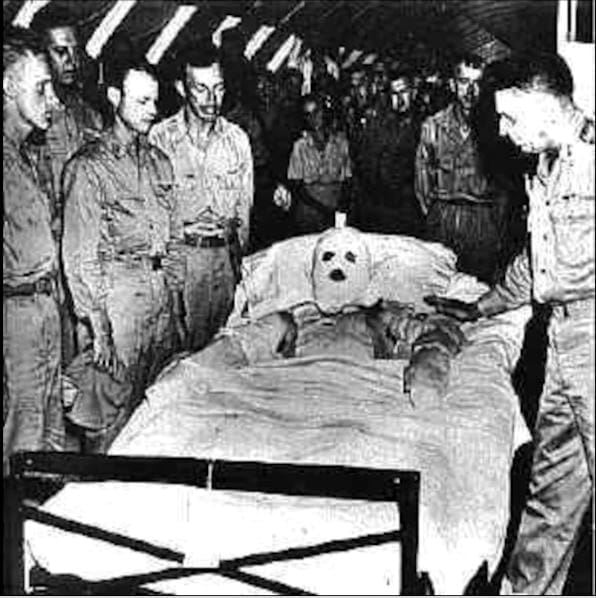

Henry Erwin Receiving His Medal of Honor

By the start of 1945, Erwin’s unit had flown a number of missions over various Japanese cities. Accounts vary on whether it was his 11th or 18th mission, but on April 12, 1945, the City of Los Angeles was the lead plane in the formation flying toward the Hodogaya Chemical Plant at Koriyama, on the island of Honshu, Japan. It was Erwin’s job to drop 20-pound phosphorous signal flares or canisters through a chute in the plane over a predetermined point to provide visual reference for the other planes in the formation. The first flare, however, did not exit the aircraft, and, burning at approximately 1,300 degrees F. (~704 degrees Celsius), hit Erwin in the face and quickly began filling the aircraft with smoke. The phosphorous also began burning through Erwin’s flight suit to his skin and through parts of the aircraft, potentially to the bomb load below according to some accounts. Holding the burning canister between his arm and body, Erwin scrambled to find a window to throw out the flare which he ultimately did from the cockpit. Crew members used fire extinguishers to douse the flames, but the phosphorus had largely burned his flight suit away, had burned through his flesh to bone in some areas, and damaged his eyes. The pilot aborted the mission and landed on the recently captured island of Iwo Jima to get Erwin prompt medical treatment. He was later moved to Guam.

Henry Erwin Receiving His Medal of Honor

By the start of 1945, Erwin’s unit had flown a number of missions over various Japanese cities. Accounts vary on whether it was his 11th or 18th mission, but on April 12, 1945, the City of Los Angeles was the lead plane in the formation flying toward the Hodogaya Chemical Plant at Koriyama, on the island of Honshu, Japan. It was Erwin’s job to drop 20-pound phosphorous signal flares or canisters through a chute in the plane over a predetermined point to provide visual reference for the other planes in the formation. The first flare, however, did not exit the aircraft, and, burning at approximately 1,300 degrees F. (~704 degrees Celsius), hit Erwin in the face and quickly began filling the aircraft with smoke. The phosphorous also began burning through Erwin’s flight suit to his skin and through parts of the aircraft, potentially to the bomb load below according to some accounts. Holding the burning canister between his arm and body, Erwin scrambled to find a window to throw out the flare which he ultimately did from the cockpit. Crew members used fire extinguishers to douse the flames, but the phosphorus had largely burned his flight suit away, had burned through his flesh to bone in some areas, and damaged his eyes. The pilot aborted the mission and landed on the recently captured island of Iwo Jima to get Erwin prompt medical treatment. He was later moved to Guam.

Henry Erwin with His Wife and Mother

Such was the severity of the burns and pain and the fear of Erwin’s seemingly imminent death that Gen. Curtis LeMay, the commander on Guam, swiftly signed a Medal of Honor citation and pushed for its approval, including Pres. Harry S. Truman’s, in recognition of Erwin’s “gallant and heroic act” to save his fellow crew members. Accounts note, however, that the only medal in all of the Pacific theater was in a locked display case at U.S. Army Headquarters in Honolulu, Hawaii. It was quickly removed and flown to Guam and presented to Erwin by Maj. Gen. Willis H. Hale, commander of Army Air Forces Pacific Area, on April 19. LeMay also had Erwin’s brother Howard, a U.S. Marine on Saipan, flown to Guam aboard a plane that was piloted by Hollywood film star and Marine Tyrone Power. LeMay would later join Alabama governor George Wallace as his vice-presidential running mate in the 1968 presidential race. Wallace also served under LeMay in the Twentieth Air Force and also flew on board a B-29 but was based at Tinian.

Henry Erwin with His Wife and Mother

Such was the severity of the burns and pain and the fear of Erwin’s seemingly imminent death that Gen. Curtis LeMay, the commander on Guam, swiftly signed a Medal of Honor citation and pushed for its approval, including Pres. Harry S. Truman’s, in recognition of Erwin’s “gallant and heroic act” to save his fellow crew members. Accounts note, however, that the only medal in all of the Pacific theater was in a locked display case at U.S. Army Headquarters in Honolulu, Hawaii. It was quickly removed and flown to Guam and presented to Erwin by Maj. Gen. Willis H. Hale, commander of Army Air Forces Pacific Area, on April 19. LeMay also had Erwin’s brother Howard, a U.S. Marine on Saipan, flown to Guam aboard a plane that was piloted by Hollywood film star and Marine Tyrone Power. LeMay would later join Alabama governor George Wallace as his vice-presidential running mate in the 1968 presidential race. Wallace also served under LeMay in the Twentieth Air Force and also flew on board a B-29 but was based at Tinian.

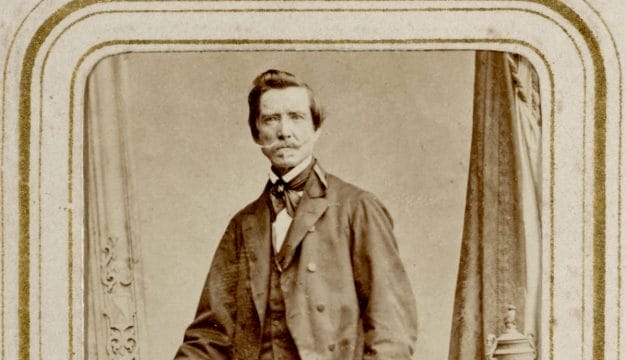

Erwin was hospitalized for 30 months and underwent some 40 often-painful surgeries, including skin grafts and having his eyes sewn shut for a long period. He eventually regained the use of one arm and some of his eyesight. He was promoted to master sergeant in 1945 and received a disability discharge, leaving the service in October 1947. In early 1948, he began working with other veterans in Birmingham, retiring in the mid-1980s.

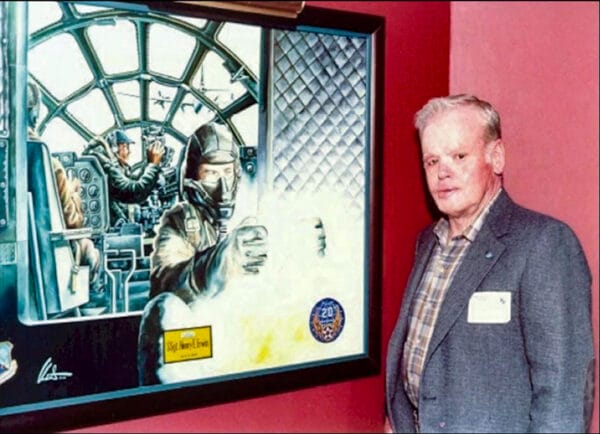

Henry Erwin, 2017

In addition to the Medal of Honor, Erwin also received the Purple Heart, the World War II Victory Medal, the American Campaign Medal, three Good Conduct Medals, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two bronze campaign stars (for participation in the Air Offensive Japan and Western Pacific campaigns), and the Distinguished Unit Citation Emblem. He was the only B-29 crewman awarded the Medal of Honor during the war. Since 1995, the U.S. Air Force has annually awarded the “Staff Sgt. Henry E. Erwin Outstanding Enlisted Aircrew Member Airman of the Year Award” to recognize career enlisted aviators for their exceptional work and leadership.

Henry Erwin, 2017

In addition to the Medal of Honor, Erwin also received the Purple Heart, the World War II Victory Medal, the American Campaign Medal, three Good Conduct Medals, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two bronze campaign stars (for participation in the Air Offensive Japan and Western Pacific campaigns), and the Distinguished Unit Citation Emblem. He was the only B-29 crewman awarded the Medal of Honor during the war. Since 1995, the U.S. Air Force has annually awarded the “Staff Sgt. Henry E. Erwin Outstanding Enlisted Aircrew Member Airman of the Year Award” to recognize career enlisted aviators for their exceptional work and leadership.

Erwin died on January 16, 2002, and was buried at Elmwood Cemetery in Birmingham. His son Hank Erwin Jr. served in the Alabama State Senate . His war-time exploits were touched on in the 1951 film Wild Blue Yonder, and he has been the subject of magazine articles and a 2020 book co-written by a grandson, Jon Erwin.

Further Reading

- Doyle, William, and Jon Erwin. Beyond Valor: A World War II Story of Extraordinary Heroism, Sacrificial Love, and a Race against Time. Nashville, Tenn.: Nelson Books, 2020.