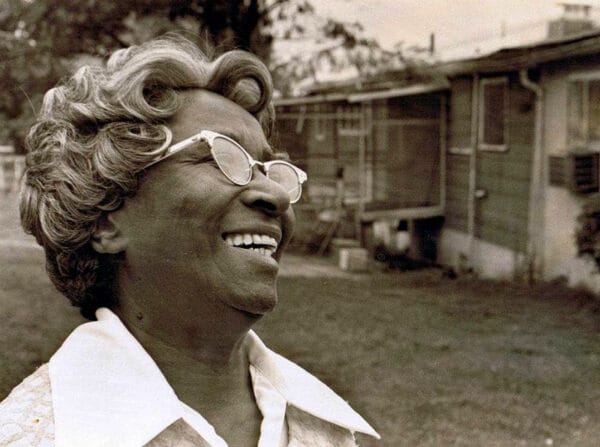

Chessie Walker Harris

Chessie Harris

Chessie Walker Harris (1906-1997) was the founder and longtime director of the Harris Home for Children in Huntsville, Madison County, a non-profit shelter that has provided support services to many thousands of disadvantaged youth since 1954. In a lifetime almost spanning the entire twentieth century, Harris was greatly molded by the epochal events that transformed the globe, notably the Great Migration, World Wars I and II, the Great Depression, and the civil rights movement. Harris was awarded the President’s Volunteer Action Award by Pres. George H. W. Bush in 1989, and the Alabama State Senate declared a statewide “Chessie Harris Day” in 1978 and 1986.

Chessie Harris

Chessie Walker Harris (1906-1997) was the founder and longtime director of the Harris Home for Children in Huntsville, Madison County, a non-profit shelter that has provided support services to many thousands of disadvantaged youth since 1954. In a lifetime almost spanning the entire twentieth century, Harris was greatly molded by the epochal events that transformed the globe, notably the Great Migration, World Wars I and II, the Great Depression, and the civil rights movement. Harris was awarded the President’s Volunteer Action Award by Pres. George H. W. Bush in 1989, and the Alabama State Senate declared a statewide “Chessie Harris Day” in 1978 and 1986.

Chessie Walker was born on January 16, 1906, in Tuskegee, Macon County, to John Thomas and Lillie Belle Walker; she had one sibling. John, a carpenter, sharecropper, and minister, and Lillie, a sharecropper and stay-at-home mother, were one generation removed from slavery. Experiencing and witnessing desperate rural poverty as an African American child in the American South, Harris resolved early on to spend her life helping less fortunate children. Believing she could accomplish this best through education, she enrolled at age 14 in Tuskegee Institute at a time when it offered preparatory schooling. She later worked in The Oaks, the home of Booker T. Washington (then deceased) for his widow Margaret Murray Washington, herself a onetime principal of Tuskegee. Harris was enriched by her time at Tuskegee, where she met notable figures such as George Washington Carver.

The Walker family migrated to Cleveland, Ohio, in the early 1920s, and were among the many millions of African Americans who migrated north for better employment and living opportunities. Chessie joined her family several years later and began inviting scores of abandoned black children into the Walker home. These so-called “street children” were wandering the streets after losing their fathers in World War I and later because of the bleak economic downturn of the Great Depression, other setbacks, or delinquency.

Chessie Harris Feeding Children

In 1933, Chessie Walker married George Ernest Harris; he had two children already and the couple would have two more children together. He was a transplanted southerner, born in Memphis, Tennessee, who had come north for industrial employment and was also deeply committed to charity work. The couple moved to a farm in Medina, Ohio, where they could comfortably raise their children and care for additional children. Faithful adherents to the Seventh-day Adventist Church, in 1949 the Harrises sent their eldest son to Oakwood Academy, the feeder school to Oakwood College (present-day Oakwood University) in Huntsville, Adventism’s sole historically black college and university (HBCU). A year later, the couple accepted jobs at Oakwood College: Chessie as food service director and George as grounds and farm manager.

Chessie Harris Feeding Children

In 1933, Chessie Walker married George Ernest Harris; he had two children already and the couple would have two more children together. He was a transplanted southerner, born in Memphis, Tennessee, who had come north for industrial employment and was also deeply committed to charity work. The couple moved to a farm in Medina, Ohio, where they could comfortably raise their children and care for additional children. Faithful adherents to the Seventh-day Adventist Church, in 1949 the Harrises sent their eldest son to Oakwood Academy, the feeder school to Oakwood College (present-day Oakwood University) in Huntsville, Adventism’s sole historically black college and university (HBCU). A year later, the couple accepted jobs at Oakwood College: Chessie as food service director and George as grounds and farm manager.

In Huntsville, Chessie Harris secured her legacy and attained national renown. She famously drove the streets of post-war Huntsville in a 1949 Buick scanning for indigent youngsters and taking them to her home for food, baths, clothes, and tutoring. Realizing that she could not fill the great need by herself, in 1953 Harris began petitioning the Huntsville Welfare Department and the Child Welfare Services of Madison County for aid and assistance for homeless children. Impatient with the bureaucracies, she focused on obtaining child-care licensing for herself and her husband. She acquired the license in June 1954, and the Harris Home for Children was officially established.

From its inception, the Harris Home was filled with children of all ages, races, and backgrounds. In lean years when there was little funding or donations, the Harrises drew from their personal expenses to keep the charitable operation running. As the reputation of the organization grew, it received state and federal assistance, support from private charitable and church organizations, and private donations. Initially, Chessie and George Harris performed the myriad jobs to keep the facility operating, but were soon joined by volunteers and finally a small staff of paid workers.

Chessie Harris Day

Throughout the four decades until her retirement in 1980, Chessie Harris was known affectionately in the community as “Mamma Harris.” Since its founding, the institution has helped more than 1,200 children from the Madison County area. It has provided disadvantaged children with housing, food, clothing, tutoring, instruction in trades, guidance and help in educational and job placement, and what is termed “life coaching” today. Many children of the Harris Home went on to have notable and societally beneficial careers in Alabama and the wider world.

Chessie Harris Day

Throughout the four decades until her retirement in 1980, Chessie Harris was known affectionately in the community as “Mamma Harris.” Since its founding, the institution has helped more than 1,200 children from the Madison County area. It has provided disadvantaged children with housing, food, clothing, tutoring, instruction in trades, guidance and help in educational and job placement, and what is termed “life coaching” today. Many children of the Harris Home went on to have notable and societally beneficial careers in Alabama and the wider world.

Harris received much recognition for her service. The Alabama Legislature on numerous occasions officially commended the Harrises for their charity work. In 1978, by gubernatorial proclamation, Alabama declared a statewide “Chessie Harris Day” and did so again in 1986. On April 11, 1989, in a ceremony held at the White House, Pres. George H. W. Bush presented the President’s Volunteer Action Award to Chessie Harris, and the Alabama Legislature again commended the Harris Home on its fortieth anniversary in 1994.

A lifelong learner, Harris furthered her education by pursuing graduate studies in various subjects at several universities. After her retirement in 1980, Harris remained active in the Harris Home and other humanitarian causes, such as services for the elderly. In 1987, Woman’s Day magazine featured Harris as an “Unsung Heroine of America.” In 1991, she was bestowed an honorary doctorate degree by Andrews University, a Seventh-day Adventist school in Michigan.

Chessie Harris died a beloved figure in Huntsville on June 6, 1997. She and her husband were both buried in Huntsville’s Northside Cemetery. The Harris Home for Children is still in operation.

Additional Resources

Griffin, Natalie A. “Chessie Harris.” In The Ladies of Oakwood. edited by Ciro Sepulveda and Lea Hardy, 45-54. Huntsville, Ala.: Oakwood College Press, 2003.

Hamblin, Madlyn. Promise in the Cornfield. Nampa, Idaho: Pacific Press, 1989.

Thomas, Leslie Nicole. Legendary Locals of Huntsville. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2016.