Hellbender

The hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis) is the third largest salamander species in the world and the largest amphibian in North America. It belongs to the Urodela Order, which encompasses all species of salamander in the world. Its genus name derives from the Greek for “hidden gill” and its species name refers to its distribution in the Allegheny River System. First described in 1803 by French zoologist François Marie Daudin, the hellbender likely received its less-than-flattering common name for its strange and alarming appearance. Hellbenders are only found within the United States, specifically confined to the Appalachian Mountains, stretching up the east coast from northern Alabama to Maine. Northernmost Alabama represents the southernmost edge of the hellbender’s range. Hellbenders have been recorded in Colbert, Franklin, Lauderdale, Limestone, Madison, Marion, and Morgan Counties.

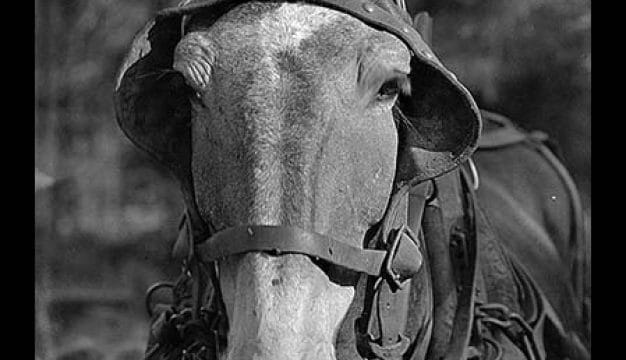

Hellbender Skin

Hellbenders weigh from approximately 3 to 5 pounds (~1.5-2.5 kilograms) as adults and vary greatly in size, ranging between 12 and 29 inches (~30-74 centimeters) in total length. They range from greenish to yellowish-brown in color, with black spots and splotches along the body, with wrinkled and folded skin around their abdomen. Larval hellbenders are uniformly dark with a white stomach. They are only about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) long at hatching and breathe through external gills, which look like two feather-like fans, that disappear as they mature. Adults are blotchy brown or reddish-brown and, like most amphibians, breathe primarily by absorbing oxygen directly into their bloodstream through their permeable skin, although they also have lungs. Hellbenders are mature and able to reproduce at 6-7 years. Hellbenders have been recorded as living up to 29 years, although some studies indicate their lifespan could be much longer, perhaps up to 50 years or more. This species’ outlandish appearance has earned it its most common name, as well nicknames that include the more affectionate term “snot otter” and “mud devil.” Despite the threatening connotations that their common names evoke, these salamanders are harmless except to their prey. Hellbenders prey on crayfish, small fish, and invertebrates and are in turn preyed upon by larger fish species. Hellbender larvae are also an important food source for predatory fish.

Hellbender Skin

Hellbenders weigh from approximately 3 to 5 pounds (~1.5-2.5 kilograms) as adults and vary greatly in size, ranging between 12 and 29 inches (~30-74 centimeters) in total length. They range from greenish to yellowish-brown in color, with black spots and splotches along the body, with wrinkled and folded skin around their abdomen. Larval hellbenders are uniformly dark with a white stomach. They are only about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) long at hatching and breathe through external gills, which look like two feather-like fans, that disappear as they mature. Adults are blotchy brown or reddish-brown and, like most amphibians, breathe primarily by absorbing oxygen directly into their bloodstream through their permeable skin, although they also have lungs. Hellbenders are mature and able to reproduce at 6-7 years. Hellbenders have been recorded as living up to 29 years, although some studies indicate their lifespan could be much longer, perhaps up to 50 years or more. This species’ outlandish appearance has earned it its most common name, as well nicknames that include the more affectionate term “snot otter” and “mud devil.” Despite the threatening connotations that their common names evoke, these salamanders are harmless except to their prey. Hellbenders prey on crayfish, small fish, and invertebrates and are in turn preyed upon by larger fish species. Hellbender larvae are also an important food source for predatory fish.

Juvenile Hellbender

Hellbenders breed in the fall, with females laying between 100 and 500 eggs in a nest prepared by the male, typically excavated underneath large submerged rocks. During mating, the male encourages the female to deposit her eggs in the nest, after which he releases sperm over them to externally fertilize them. The eggs are laid in two strands, with each yellow, spherical egg attached to the next in a long string. The male then guards the clutch of eggs for two months until they hatch.

Juvenile Hellbender

Hellbenders breed in the fall, with females laying between 100 and 500 eggs in a nest prepared by the male, typically excavated underneath large submerged rocks. During mating, the male encourages the female to deposit her eggs in the nest, after which he releases sperm over them to externally fertilize them. The eggs are laid in two strands, with each yellow, spherical egg attached to the next in a long string. The male then guards the clutch of eggs for two months until they hatch.

Hellbenders are entirely aquatic salamanders, meaning they live their whole lives in their freshwater stream habitats. They prefer free-flowing streams with large, flat rocks at the bottom to hide under. Their flattened appearance is an adaptation to this habitat. Hellbenders seem to prefer clearer water over cloudy and heavily silted waters. Younger hellbenders prefer some sort of substrate at the bottom of the stream to provide more protection as they grow and mature.

Hellbender

Like most amphibians, hellbenders face a number of threats to their survival. The species has a rank of S2, which means it is “imperiled” in the state of Alabama, and a rank of P1, which is the Priority 1 or the highest conservation concern in its State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP) submitted to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The P1 rank in particular means that immediate action is needed to conserve the species and that the species is in decline primarily owing to human actions. Because of their permeable skin as amphibians, hellbenders are especially susceptible to pollution. Additionally, construction, dams, runoff, and other human-caused disturbances are a threat to the clean and swift-flowing streams and large rock cover they require for shelter and feeding. In terms of the conservation of species, it is important to consider their value. The hellbender benefits humans without being harvested itself because it operates as a bioindicator. Bioindicators are species in an ecosystem that indicate the overall health of that ecosystem. Because of the hellbender’s sensitivity to water and habitat quality, its presence or absence in a particular environment indicates levels of water quality and other aspects of the health of that system. Their decline indicates that many of Alabama’s river systems are under threat.

Hellbender

Like most amphibians, hellbenders face a number of threats to their survival. The species has a rank of S2, which means it is “imperiled” in the state of Alabama, and a rank of P1, which is the Priority 1 or the highest conservation concern in its State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP) submitted to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The P1 rank in particular means that immediate action is needed to conserve the species and that the species is in decline primarily owing to human actions. Because of their permeable skin as amphibians, hellbenders are especially susceptible to pollution. Additionally, construction, dams, runoff, and other human-caused disturbances are a threat to the clean and swift-flowing streams and large rock cover they require for shelter and feeding. In terms of the conservation of species, it is important to consider their value. The hellbender benefits humans without being harvested itself because it operates as a bioindicator. Bioindicators are species in an ecosystem that indicate the overall health of that ecosystem. Because of the hellbender’s sensitivity to water and habitat quality, its presence or absence in a particular environment indicates levels of water quality and other aspects of the health of that system. Their decline indicates that many of Alabama’s river systems are under threat.

Further Reading

- Graham, Sean P., Eric C. Soehren, and William B. Sutton. “Conservation Status of Hellbenders (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis) in Alabama, USA.” Journal of Herpetology 5 (1971): 121-26.

- Nickerson, Max A., and Kenneth L. Krysko. “Surveying for Hellbender Salamanders, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis (Daudin): A Review and Critique.” Applied Herpetology 1 (2003): 37-44.