Woodpeckers of Alabama

Northern Flicker

Woodpeckers encompass 210 species of birds best known for their distinctive “head-banging” behavior. They belong to the order Piciformes and the family Picidae, which can be found worldwide except for Madagascar, Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, and the polar regions. Alabama is home to eight species of woodpeckers, with a ninth species, the ivory-billed woodpecker, widely believed to be extirpated. These eight species are the downy woodpecker, hairy woodpecker, red-bellied woodpecker, red-headed woodpecker, pileated woodpecker, yellow-bellied sapsucker, northern flicker (the state bird colloquially known as Yellowhammer), and the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker.

Northern Flicker

Woodpeckers encompass 210 species of birds best known for their distinctive “head-banging” behavior. They belong to the order Piciformes and the family Picidae, which can be found worldwide except for Madagascar, Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, and the polar regions. Alabama is home to eight species of woodpeckers, with a ninth species, the ivory-billed woodpecker, widely believed to be extirpated. These eight species are the downy woodpecker, hairy woodpecker, red-bellied woodpecker, red-headed woodpecker, pileated woodpecker, yellow-bellied sapsucker, northern flicker (the state bird colloquially known as Yellowhammer), and the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker.

The family Picidae was first proposed by English zoologist William Elford Leach in 1820 based his study of specimens in the British Museum (now the Natural History Museum, London). Modern genetic analyses later confirm that all the birds within the family Picidae have a shared ancestor. Members of the Picidae are all cavity nesters and have zygodactyl feet (two toes facing forward and two facing backward) that help them move on vertical tree trunks. There are four subfamilies within the Picidae: Picinae (woodpecker subfamily), Picumninae (piculet subfamily), Jynginae (wryneck subfamily), and Nesoctitinae (Antillean piculet subfamily). The only subfamily found in Alabama is the Picinae.

In most woodpecker species, both males and females work together to excavate nest cavities in dead trees, limbs of trees, or fence posts. Typically, a pair of woodpeckers excavates one cavity for the breeding season, and they often have alternative cavities for sleeping. Given the time and effort spent to build these cavities, woodpeckers will aggressively defend their nest holes from other potential competitors. Nesting cavities typically have a round opening that leads to an enlarged hollow chamber where the female lays her eggs. The number of eggs laid per clutch ranges from two to six eggs for the red-bellied woodpecker and from three to ten eggs for the red-headed woodpecker. Females incubate the eggs for 11 to 20 days, depending on the species. Woodpecker eggs are white with no markings. Hatchlings are born naked and helpless and develop in the nest from 18 to 30 days before fledging. During this time, both parents take turns feeding the young. Most woodpecker species in Alabama breed once per year in late April and May and have one brood per season. Red-bellied woodpecker pairs, however, can have up to three broods per year. Most woodpeckers reach sexual maturity within a year. Woodpeckers create more cavities than they can simultaneously occupy, and unused woodpecker cavities are important nest sites for other species, such as great-crested flycatchers and eastern bluebirds, that cannot excavate their own holes. Mammals like bats and rodents may inhabit these abandoned holes as well.

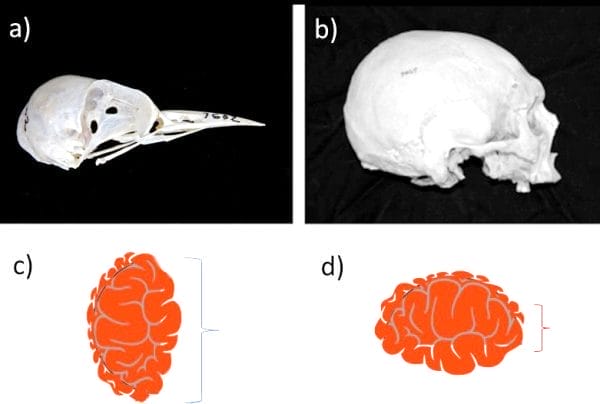

Woodpecker and Human Skull Comparison

Woodpeckers communicate by calling and drumming. Woodpecker calls are generally repeated short sequences, but the pitch and frequencies differ among species. Woodpecker drumming is a form of communication that involves forceful banging of the beak on solid surfaces. Birds in urban areas also take advantage of manufactured materials that amplify sound such as gutters, chimneys, vents, and even barbeque grills as drumming surfaces. Such behavior in humans would cause brain injury, but woodpeckers can repeatedly knock their heads safely into solid surfaces. Multiple scientific studies suggest that the unique structure of a woodpecker’s skull and beak enables them to absorb the shock. The upper beak is longer than the lower beak, which helps divert the force of impact to the lower jaw. The bones at the front of the skull are spongy at the interior, and this structure cushions the brain within the skull during drumming. In addition, woodpeckers have an unusually elongated hyoid apparatus, a type of structure found in the throats of many animals at the base of the tongue. In woodpeckers, the hyoid apparatus extends from the top of the skull to the mouth, where it attaches to the tongue. This structure serves as a brace for the skull every time the bird pecks and also helps prevent damage to the brain. Even when there is contact between the brain and the skull, the brain is oriented so that any potential contact with the skull is spread out and diffused, which reduces the stress on any one area that could lead to brain injury, as shown in Figure 1.

Woodpecker and Human Skull Comparison

Woodpeckers communicate by calling and drumming. Woodpecker calls are generally repeated short sequences, but the pitch and frequencies differ among species. Woodpecker drumming is a form of communication that involves forceful banging of the beak on solid surfaces. Birds in urban areas also take advantage of manufactured materials that amplify sound such as gutters, chimneys, vents, and even barbeque grills as drumming surfaces. Such behavior in humans would cause brain injury, but woodpeckers can repeatedly knock their heads safely into solid surfaces. Multiple scientific studies suggest that the unique structure of a woodpecker’s skull and beak enables them to absorb the shock. The upper beak is longer than the lower beak, which helps divert the force of impact to the lower jaw. The bones at the front of the skull are spongy at the interior, and this structure cushions the brain within the skull during drumming. In addition, woodpeckers have an unusually elongated hyoid apparatus, a type of structure found in the throats of many animals at the base of the tongue. In woodpeckers, the hyoid apparatus extends from the top of the skull to the mouth, where it attaches to the tongue. This structure serves as a brace for the skull every time the bird pecks and also helps prevent damage to the brain. Even when there is contact between the brain and the skull, the brain is oriented so that any potential contact with the skull is spread out and diffused, which reduces the stress on any one area that could lead to brain injury, as shown in Figure 1.

Worldwide, woodpeckers occupy a variety of habitats, from tropical rainforest to grasslands to desert. In Alabama, all species require trees but they are found from the interior of large forests to individual trees in pastures. For most species, ideal habitat includes rotting or dead wood that harbors insect prey and affords places to build nest cavities. In Alabama, however, northern flickers reach their highest densities in small towns and suburbs, where they feed on lawns and sometimes nest and roost in shingles or wooden siding of houses. Most woodpeckers in Alabama are non-migratory, meaning they remain in the same habitat year-round, but the yellow-bellied sapsucker is highly migratory and only visits Alabama in the winter.

Woodpecker Skull

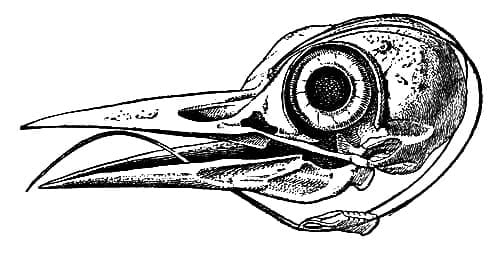

Adult woodpeckers forage for fruits, seeds, and nuts, but their main diet consists of insects. As mentioned above, in woodpeckers, the hyoid apparatus extends to the tip of their tongues and the fork sits in front of the throat, where the muscle responsible for extending and retracting the tongue attaches. In some species, the tongue splits in two at the back and extends up and around the skull and ends at the nasal cavity when retracted (see Figure 2). This unique morphology allows woodpeckers to extend their tongue about three times the length of their beaks. Their tongues also have an assortment of backward-projecting barbs near the tip that allow them to rake insects out of a hole as they retract it. Yellow-bellied sapsuckers are unusual in relying on sap as their main food source, drilling series of holes in trees and returning to them often to drink the sugary, energy-laden sap that seeps out. Woodpeckers, in turn, are preyed up on by larger predatory birds like hawks and by mammalian predators such as foxes, bobcats, coyotes, and domestic and feral cats. Woodpecker eggs and nestlings are prized by snakes and flying squirrels.

Woodpecker Skull

Adult woodpeckers forage for fruits, seeds, and nuts, but their main diet consists of insects. As mentioned above, in woodpeckers, the hyoid apparatus extends to the tip of their tongues and the fork sits in front of the throat, where the muscle responsible for extending and retracting the tongue attaches. In some species, the tongue splits in two at the back and extends up and around the skull and ends at the nasal cavity when retracted (see Figure 2). This unique morphology allows woodpeckers to extend their tongue about three times the length of their beaks. Their tongues also have an assortment of backward-projecting barbs near the tip that allow them to rake insects out of a hole as they retract it. Yellow-bellied sapsuckers are unusual in relying on sap as their main food source, drilling series of holes in trees and returning to them often to drink the sugary, energy-laden sap that seeps out. Woodpeckers, in turn, are preyed up on by larger predatory birds like hawks and by mammalian predators such as foxes, bobcats, coyotes, and domestic and feral cats. Woodpecker eggs and nestlings are prized by snakes and flying squirrels.

Woodpecker Species in Alabama

Pileated Woodpecker

The pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) is the largest woodpecker in Alabama, at 16 to 19 inches (~ 40-49 centimeters) in length and the second largest in North America, following the likely extinct ivory-billed woodpecker (although recent sightings have been reported in the swamps of Arkansas and Florida), which reached 18 to 20 inches (~ 46-51 centimeters) in length. Both male and female pileated woodpeckers have black plumage with white stripes on the neck and face topped with an iconic flaming-red crest. They can be found year-round in Alabama. Their preferred habitat is mature deciduous or mixed deciduous-coniferous woodlands.

Pileated Woodpecker

The pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) is the largest woodpecker in Alabama, at 16 to 19 inches (~ 40-49 centimeters) in length and the second largest in North America, following the likely extinct ivory-billed woodpecker (although recent sightings have been reported in the swamps of Arkansas and Florida), which reached 18 to 20 inches (~ 46-51 centimeters) in length. Both male and female pileated woodpeckers have black plumage with white stripes on the neck and face topped with an iconic flaming-red crest. They can be found year-round in Alabama. Their preferred habitat is mature deciduous or mixed deciduous-coniferous woodlands.

The northern flicker (Colaptes auratus) is a relatively large bird, at about a foot (~28-31 centimeters) in length with a flared tail that tapers at the end. The flicker is brown overall but has a conspicuous white rump patch during flight. It is the state bird of Alabama and colloquially known as the “yellowhammer” for its bright yellow underwings and loud drumming. There are two different subspecies: Colaptes auratus auratus (yellow-shafted) and Colaptes auratus cafer (red-shafted). Only the yellow-shafted subspecies is found in Alabama. This short-distance migratory bird can be found year-round in Alabama in open woodlands, forest edges, and urban parks and neighborhoods with trees.

Red-bellied Woodpecker

Red-bellied woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus) reach approximately 9.5 inches (~24 centimeters) in length as adults and have a white underside and face, black-and-white striped wings and tail, and a prominent red crown covering on top of the head. The patch is much larger and brighter in the males. They are the most common woodpecker in the Southeast and can be found throughout the year in Alabama. They prefer forests and woodlands, but they can often be seen in suburban yards and parks and unlike other woodpeckers, prefer fruit to insects.

Red-bellied Woodpecker

Red-bellied woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus) reach approximately 9.5 inches (~24 centimeters) in length as adults and have a white underside and face, black-and-white striped wings and tail, and a prominent red crown covering on top of the head. The patch is much larger and brighter in the males. They are the most common woodpecker in the Southeast and can be found throughout the year in Alabama. They prefer forests and woodlands, but they can often be seen in suburban yards and parks and unlike other woodpeckers, prefer fruit to insects.

Red-headed woodpeckers (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) are medium-sized woodpeckers ranging from 7.5 to 9 inches (~19-23 centimeters) in length. The red-headed woodpecker is one of the most spectacularly colored woodpeckers. As the name suggests, it has a large, rounded bright red head as well as a short, stiff tail, black wings with large white patches, and bright white undersides that contrast noticeably in flight. Juveniles have gray-brown heads and incomplete white patches on their wings, which gives them a striped appearance. They are fairly common in Alabama all year except winter. They reach their highest density in recently cut forest in which dead snags are left standing. Red-headed woodpeckers are unusual in being adept aerial insect catchers, though most of their diet consists of plant materials, especially acorns.

The yellow-bellied sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius) averages around 7 to 9 inches (~18-23 centimeters) in length. It has a black and white body and a bold black and white face with a red forehead (males also have red throats). Yellow-bellied sapsuckers are migratory birds that breed in the north (throughout Canada) and spend their nonbreeding season in the South (eastern United States and throughout Central America).

Red-cockaded Woodpecker

The red-cockaded woodpecker (Dryobates borealis) averages 8 to 9 inches (~ 20-21 centimeters) in length. It is black and white on top and white with black spots on the underside; males have tiny “cockade” (red streak) at the upper border of the white cheeks. This species is strongly dependent on old-growth pine forest that burns frequently and is thus critically endangered throughout its range. The red-cockaded woodpecker is the only species in Alabama that lives in family groups and raises young cooperatively.

Red-cockaded Woodpecker

The red-cockaded woodpecker (Dryobates borealis) averages 8 to 9 inches (~ 20-21 centimeters) in length. It is black and white on top and white with black spots on the underside; males have tiny “cockade” (red streak) at the upper border of the white cheeks. This species is strongly dependent on old-growth pine forest that burns frequently and is thus critically endangered throughout its range. The red-cockaded woodpecker is the only species in Alabama that lives in family groups and raises young cooperatively.

The downy woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) is the smallest woodpecker in Alabama, ranging between 5.5 to 6.7 inches (~14-17 centimeters) in length. Apart from their small size, they are distinguished by their checkered black-and-white pattern, two bold white stripes on the head (males also have small red patch on the back of the head), and a broad white stripe down the center of the back. Downy woodpeckers occur year-round throughout Alabama and can be found in forested areas as well as urban parks and backyards.

The hairy woodpecker (Picoides villosus) is rarely sighted in Alabama. It averages 7 to 10 inches (~ 18-25 centimeters) in length and has a white underside and black wings with white speckling. It inhabits woodlands.

The ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) was a relatively common resident of forested wetlands in south Alabama until the late nineteenth century. Following the Civil War, many local populations were hunted to extinction. A small population is thought to persist in the Florida panhandle just south of Alabama, but the last confirmed bird in Alabama was shot in the Conecuh River swamps north of Troy in 1907.

Threats

Downy Woodpecker

Deforestation and conversion of woodland for agriculture and other purposes have dramatically reduced woodpecker populations in Alabama. Indeed, the ivory-billed woodpecker is considered extinct by most experts despite recent reported sightings in Arkansas and Florida. Historically in Alabama, it was found in thick hardwood swamps and pine forests around Dallas, Hale, Lamar, Marengo, Pike, and Wilcox Counties. Fire suppression is another factor that has led to declines in woodpecker populations, particularly the federally endangered red-cockaded woodpecker, that rely on frequently burned old growth pine forest. State wildlife biologists are implementing land-management efforts to aid the red-cockaded woodpecker, but they are largely restricted to Oakmulgee Wildlife Management Area, Talladega and Conecuh National Forests, and a few private lands. The use of pesticides and insecticides on species consumed by woodpeckers also indirectly affects the birds through accumulation of toxins over time.

Downy Woodpecker

Deforestation and conversion of woodland for agriculture and other purposes have dramatically reduced woodpecker populations in Alabama. Indeed, the ivory-billed woodpecker is considered extinct by most experts despite recent reported sightings in Arkansas and Florida. Historically in Alabama, it was found in thick hardwood swamps and pine forests around Dallas, Hale, Lamar, Marengo, Pike, and Wilcox Counties. Fire suppression is another factor that has led to declines in woodpecker populations, particularly the federally endangered red-cockaded woodpecker, that rely on frequently burned old growth pine forest. State wildlife biologists are implementing land-management efforts to aid the red-cockaded woodpecker, but they are largely restricted to Oakmulgee Wildlife Management Area, Talladega and Conecuh National Forests, and a few private lands. The use of pesticides and insecticides on species consumed by woodpeckers also indirectly affects the birds through accumulation of toxins over time.

Additional Resources

Gibson, Lorna J. “Woodpecker Pecking: How Woodpeckers Avoid Brain Injury.” Journal of Zoology 270, no. 3 (2006): 462-65.

Peterson, Roger Tory. Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008.

Wang, Lizhen, Jason Tak-Man Cheung, Fang Pu, Deyu Li, Ming Zhang, and Yubo Fan. “Why Do Woodpeckers Resist Head Impact Injury: A Biomechanical Investigation.” PLOS One 6, no. 10 (2011): e26490.