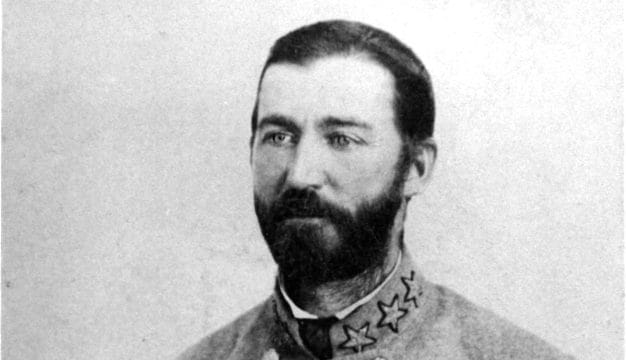

Fred Leonard Blackmon

Fred Leonard Blackmon (1873-1921) served as a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1911 to 1921 representing Alabama’s Fourth Congressional District. His greatest accomplishment during his two decades in politics is his role in prompting the expansion of Fort McClellan from a small military camp to a major military installation during World War I. By the standards of the era, Blackmon was extremely progressive and considered one of the most liberal legislators during his time in office, opposing Prohibition and the draft.

Fred Leonard Blackmon

Blackmon was born to Augustus and Sallie Blackmon in Lime Branch, a small community a few miles from modern day Cedartown, Georgia, on September 15, 1873. He was the youngest of two children. In addition to farming, Blackmon’s father worked as a physician. Blackmon was also a childhood friend of future liberal Georgia senator William J. Harris, whose father was also Cedartown physician. (Harris would later marry Julia Knox Hull Wheeler, daughter of Alabama military figure and politician Joseph Wheeler.) When Blackmon was about ten, his family resettled in nearby Calhoun County, Alabama. He attended the public schools in Dearmanville and Choccolocco and continued his studies at the State Normal School at Jacksonville, Calhoun County, (present-day Jacksonville State University) and Douglasville College in Georgia. Blackmon also studied business in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and then earned a law degree from the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, in 1894. Blackmon was admitted to the state bar the same year and started practicing in Anniston, Calhoun County, with the prominent Knox, Bowie & Pelham firm. It rose to further distinction in the area of corporate law under the name Knox, Acker & Blackmon after Blackmon became a partner and Sydney Johnston Bowie was elected to Congress, in 1900. Blackmon married the widowed Mary Agnes Bellenger Cox in 1908; the couple would have two children. He was an active member of several fraternal brotherhoods, including the Knights of Pythias, Odd Fellows, and the Elks.

Fred Leonard Blackmon

Blackmon was born to Augustus and Sallie Blackmon in Lime Branch, a small community a few miles from modern day Cedartown, Georgia, on September 15, 1873. He was the youngest of two children. In addition to farming, Blackmon’s father worked as a physician. Blackmon was also a childhood friend of future liberal Georgia senator William J. Harris, whose father was also Cedartown physician. (Harris would later marry Julia Knox Hull Wheeler, daughter of Alabama military figure and politician Joseph Wheeler.) When Blackmon was about ten, his family resettled in nearby Calhoun County, Alabama. He attended the public schools in Dearmanville and Choccolocco and continued his studies at the State Normal School at Jacksonville, Calhoun County, (present-day Jacksonville State University) and Douglasville College in Georgia. Blackmon also studied business in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and then earned a law degree from the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, in 1894. Blackmon was admitted to the state bar the same year and started practicing in Anniston, Calhoun County, with the prominent Knox, Bowie & Pelham firm. It rose to further distinction in the area of corporate law under the name Knox, Acker & Blackmon after Blackmon became a partner and Sydney Johnston Bowie was elected to Congress, in 1900. Blackmon married the widowed Mary Agnes Bellenger Cox in 1908; the couple would have two children. He was an active member of several fraternal brotherhoods, including the Knights of Pythias, Odd Fellows, and the Elks.

Blackmon’s first foray into politics was his service as Anniston’s city attorney from 1894 to 1902. He was then elected to the Alabama Senate as a Democrat, representing primarily Calhoun County from 1900 to 1910. Blackmon was an active legislator serving as chairman of the committee on rules and a member of the committees on corporations, commerce, education, and temperance. Soon after ending his time in the Senate, Blackmon was encouraged to run for Alabama’s Fourth Congressional District following the retirement of William Benjamin Craig. The district included Dallas, Shelby, Talladega, Chilton, Cleburne, and Calhoun Counties. After winning the office, Blackmon was reelected four times, serving from 1911 until his death in 1921. During this period, Blackmon faced only one tough election and earned a reputation as a progressive.

On the issues of his day, Blackmon most often aligned with the left wing of his party, although he would join most of his fellow southerners in opposing the 19th Amendment extending the right to vote to women. As for the other key issues of the era, Blackmon voted for the April 1917 declaration of war against Germany but did vote on the Selective Service Act of 1917 (draft) that was approved by the House later that month. He voted against both the 18th Amendment enacting Prohibition and the Volstead Act, which provided the government the power to enforce Prohibition. These votes, as well as his general opposition to Prohibition, put him at odds with many of his constituents and other southern politicians who mostly supported the policy. He also served on the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads and was remembered by his fellow congressmen as a humble legislator who rarely engaged in debates or political feuds. He occasionally incorporated his background into his campaign speeches by recollecting the times he had worked alongside his future constituents who could not afford to pay their road taxes in cash and instead paid through volunteer work.

After touring an artillery range in Tennessee prior to World War I, Blackmon had recognized that the Choccolocco Mountains in his district were also well suited for artillery training and his lobbing led to the War Department to begin expanding McClellan military installation. Blackmon supporters were so grateful for his efforts to expand the facility from a small camp to a more permanent facility that they tried to have the fort renamed in his honor.

Blackmon’s district had more two-party competition than most in the South but it was his final election in 1920 that proved the most competitive. In the Democratic primary, Blackmon faced Lamar Jeffers, who had returned from World War I a hero, having earned the Distinguished Service Cross for valor during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Blackmon prevailed and faced Adolphus Longshore, who had served two terms in the state legislature as a Democrat before feuds with party leaders led him to associate with the Populist and Republican parties. Longshore was a rare political figure in the Democrat-dominated Alabama, capable of winning office as a county probate judge as a Republican. Longshore enjoyed strong support in his race against Blackmon, and did much better than in their 1912 contest, but Blackmon again emerged victorious.

Blackmon served little of this hard-won term, dying on February 8, 1921, in Bartow, Florida. A few weeks prior during a congressional memorial for the late Alabama senator John Hollis Bankhead, some of Blackmon’s colleagues noted that he appeared ill. His doctor recommended that a warmer climate would do him some good, prompting the trip to Florida. The 47-year-old congressman’s death followed suddenly. Blackmon was buried at Hillside Cemetery in Anniston. After his passing, his former political rivals Jeffers and Longshore competed in a special election to succeed him in Congress, with Jeffers emerging the victor.