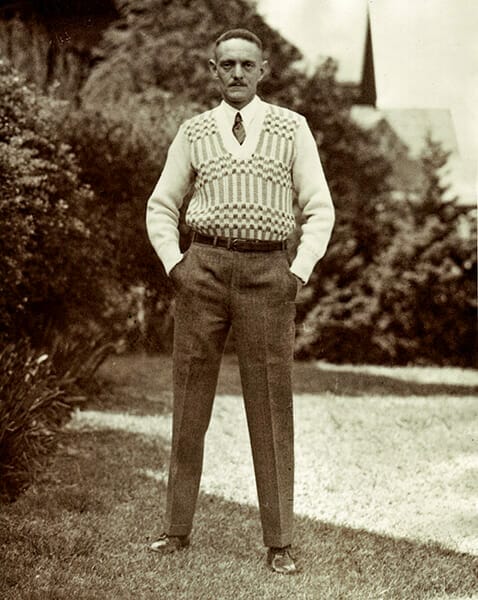

Octavus Roy Cohen

Octavus Roy Cohen

Octavus Roy Cohen (1891-1959) was a journalist and prolific author of fiction who published more than 60 novels and short-story collections, five plays, and 30 film scripts. He spent many years in Birmingham, Jefferson County, and his experiences inspired him to write 250 short stories centering on African American life in the 1910s. Writing from a white man’s perspective, however, Cohen’s Birmingham stories contain racially biased stereotypes, humor, and language that drew criticism even at the time they were published. During his lifetime, many films were adapted from his works, but he is largely forgotten today.

Octavus Roy Cohen

Octavus Roy Cohen (1891-1959) was a journalist and prolific author of fiction who published more than 60 novels and short-story collections, five plays, and 30 film scripts. He spent many years in Birmingham, Jefferson County, and his experiences inspired him to write 250 short stories centering on African American life in the 1910s. Writing from a white man’s perspective, however, Cohen’s Birmingham stories contain racially biased stereotypes, humor, and language that drew criticism even at the time they were published. During his lifetime, many films were adapted from his works, but he is largely forgotten today.

Cohen was born on June 26, 1891, in Charleston, South Carolina, to Montgomery native Octavus Cohen, a journalist and lawyer, and Rebecca O. Cohen. In 1911, he graduated from Clemson College (now Clemson University) with a degree in engineering. Sources indicate that he moved to Birmingham to work for the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company prior to his graduation. He had begun writing for newspapers before finishing college, and during his first brief time in Birmingham wrote for The Birmingham Ledger newspaper.

By 1912, Cohen was back in Charleston, clerking in his father’s law office. He passed the state bar exam in 1913 and set up his own law practice. He also began writing his earliest published short stories, several of which centered on baseball. He soon returned to Alabama and in October 1914 married Inez Lopez in Bessemer; the couple would have one son, Octavus Roy Cohen Jr. The Cohens remained in the Birmingham area until 1935 and then moved to New York and then Los Angeles.

Octavus Roy Cohen

Cohen is probably best known for his stories and novels featuring three different private detectives. David Carroll, an atypical young and enthusiastic private eye, appeared in four of Cohen’s early novels: The Crimson Alibi (1919), Gray Dusk (1919), Six Seconds of Darkness (1921), and Midnight (1922). The Crimson Alibi was so popular that it was adapted as a play and ran on Broadway for a few weeks in the summer of 1919. Cohen’s character Jim Hanvey, a shabby, folksy, obese detective, appears in three novels and in many stories collected in several books, such as Jim Hanvey, Detective (1923) and Scrambled Yeggs (1934). The character was also the subject of the 1937 film Jim Hanvey, Detective from Republic Studios. Cohen’s third detective, Florian Slappey, is one of the earliest black private investigators. He appears in numerous stories published first in the Saturday Evening Post and then in such collections as Florian Slappey Goes Abroad (1928) and Florian Slappey (1938). Despite the relative uniqueness of the character at the time, the stories, focusing on middle-class African American society in Birmingham, make for painful reading today. They are overloaded with stereotypes, vernacular language, and slang exaggerated for comic effect. These Birmingham stories were very popular but raised many objections from both whites and blacks in print even at the time of their publication. Book reviewer Melville J. Herskovits described them as “a travesty and a caricature” and noted that the people portrayed in the stories were found in fiction and not in real life.

Octavus Roy Cohen

Cohen is probably best known for his stories and novels featuring three different private detectives. David Carroll, an atypical young and enthusiastic private eye, appeared in four of Cohen’s early novels: The Crimson Alibi (1919), Gray Dusk (1919), Six Seconds of Darkness (1921), and Midnight (1922). The Crimson Alibi was so popular that it was adapted as a play and ran on Broadway for a few weeks in the summer of 1919. Cohen’s character Jim Hanvey, a shabby, folksy, obese detective, appears in three novels and in many stories collected in several books, such as Jim Hanvey, Detective (1923) and Scrambled Yeggs (1934). The character was also the subject of the 1937 film Jim Hanvey, Detective from Republic Studios. Cohen’s third detective, Florian Slappey, is one of the earliest black private investigators. He appears in numerous stories published first in the Saturday Evening Post and then in such collections as Florian Slappey Goes Abroad (1928) and Florian Slappey (1938). Despite the relative uniqueness of the character at the time, the stories, focusing on middle-class African American society in Birmingham, make for painful reading today. They are overloaded with stereotypes, vernacular language, and slang exaggerated for comic effect. These Birmingham stories were very popular but raised many objections from both whites and blacks in print even at the time of their publication. Book reviewer Melville J. Herskovits described them as “a travesty and a caricature” and noted that the people portrayed in the stories were found in fiction and not in real life.

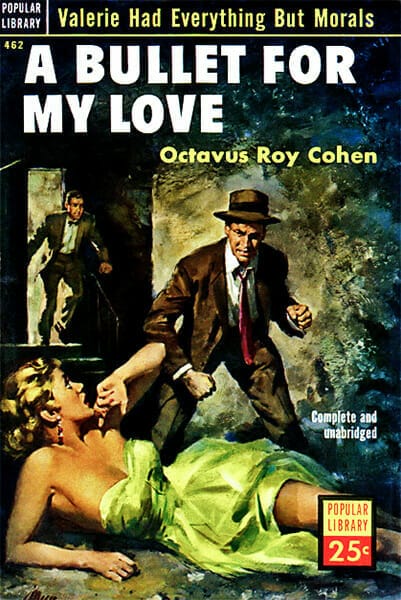

Octavus Roy Cohen Novel

During the 1920s, Cohen frequently hosted a group of local writers and journalists at his apartment on 21st Street South to discuss fiction writing. The group included such successful authors as Jack Bethea, Edgar Valentine Smith, Petterson Marzoni, and James Saxon Childers. Some sources note that Cohen received an honorary doctorate in literature from Birmingham-Southern College in 1927, perhaps a result of his growing fame as a writer.

Octavus Roy Cohen Novel

During the 1920s, Cohen frequently hosted a group of local writers and journalists at his apartment on 21st Street South to discuss fiction writing. The group included such successful authors as Jack Bethea, Edgar Valentine Smith, Petterson Marzoni, and James Saxon Childers. Some sources note that Cohen received an honorary doctorate in literature from Birmingham-Southern College in 1927, perhaps a result of his growing fame as a writer.

In the fall of 1945, Cohen worked briefly on the CBS-TV production of The Amos ‘n’ Andy Show. Apparently he was unable to adapt to this medium, as he left after six weeks, but by that time, he had moved on to different subject matter for his fiction. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, he was publishing short stories in such places as Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and The Saint Detective Magazine. He also published some crime thrillers, including My Love Wears Black (1948) and The Corpse That Walked (1951).

Cohen died in Los Angeles of a stroke on January 6, 1959, and was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. His rather lengthy obituary in the New York Times described him as retired. His wife Inez had died in 1953.

Further Reading

- Bloomer, John W. ” ‘The Loafers’ in Birmingham in the Twenties.” Alabama Review 30 (April 1977): 101-7.

- “Octavus Roy Cohen Dead at 67; Known for Stories of the South.” New York Times, January 7, 1959, p. 30.