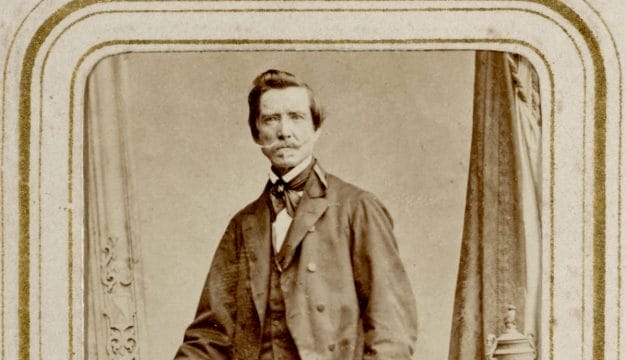

Robert Posey

Robert Posey

Alabama native Robert Kelley Posey (1904-1977) was among a select group of Monuments, Fine Arts & Archives Officers (MFA&A), known as “Monuments Men,” who during World War II were charged with protecting historic buildings, landmarks, and monuments in Europe. Trained as an architect at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (API; present-day Auburn University), Posey is most noted for recovering Jan van Eyck’s 1432 masterpiece The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, also referred to as the Ghent Altarpiece, as well as many other works looted from European cities by the Germans.

Robert Posey

Alabama native Robert Kelley Posey (1904-1977) was among a select group of Monuments, Fine Arts & Archives Officers (MFA&A), known as “Monuments Men,” who during World War II were charged with protecting historic buildings, landmarks, and monuments in Europe. Trained as an architect at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (API; present-day Auburn University), Posey is most noted for recovering Jan van Eyck’s 1432 masterpiece The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, also referred to as the Ghent Altarpiece, as well as many other works looted from European cities by the Germans.

Posey was born on April 5, 1904, in Morris, Jefferson County, to Mary-Kelly and James Wesley Posey. Posey was the third of seven children. The family moved to Tarrant, a working-class neighborhood north of Birmingham, when he was 13. Posey attended Birmingham’s Central High School, graduating in the spring of 1922. Posey’s family, like many in Alabama at that time, was poor, but he was able to attend API in Auburn, Lee County, on a Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) scholarship. Posey was supposed to switch out every other year with his brother, Owen, so both could attend college, but Robert did so well that he stayed at Auburn and completed two degrees: a B.S. in Architectural Engineering in 1926 and a B.S. in Architecture in 1927. At the same time, Posey was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Reserves. (He would hold that rank until his promotion to first lieutenant on April 1, 1940.)

After graduating in 1927, Posey moved to Birmingham, where he joined the architectural firm Miller, Martin & Lewis. He worked on Robert Jemison Jr.’s development of Mountain Brook Village, with its English Tudor-style architecture and naturalistic design layout. Following the financial crash of 1929, he moved to New York in search of better opportunities. Shortly thereafter, Posey enrolled in post-graduate work at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, earning a certificate in architectural design in 1932. The following year, he married New York native Alice Gwendolyn Montgomery; the couple would have two children.

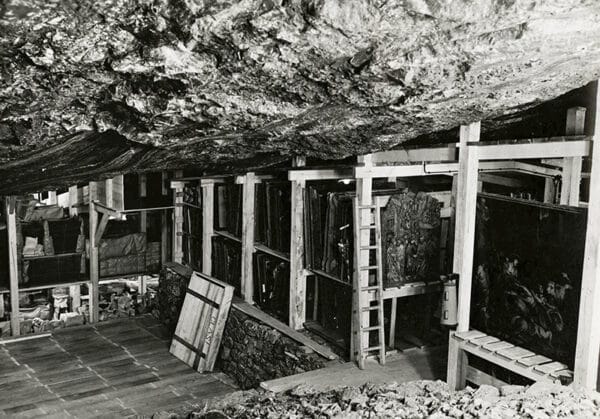

Artworks in Salt Mine

When the United States entered World War II after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, Posey wanted to join the fight, but it would be another half year before he received orders from the Reserves. Posey then went through several training programs in various locations, most notably in civil-military affairs that provided intensive instruction in the history, culture, and languages (particularly French) of those countries the United States and its allies were likely to occupy. In early March 1944, Posey, now a captain, was posted to the newly established Civil Affairs Center at Shrivenham, England, where he was assigned to the Civil Affairs Training School to await his next assignment. In early 1944, Posey was selected for MFA&A duty by its deputy chief, Col. Henry C. Newton, an architect from Los Angeles. Newton had found Posey’s name on a list of all architects on active duty from the American Institute of Architects. Posey was assigned as a Monuments Officer with Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army later that spring and arrived in Normandy, France, in July 1944.

Artworks in Salt Mine

When the United States entered World War II after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, Posey wanted to join the fight, but it would be another half year before he received orders from the Reserves. Posey then went through several training programs in various locations, most notably in civil-military affairs that provided intensive instruction in the history, culture, and languages (particularly French) of those countries the United States and its allies were likely to occupy. In early March 1944, Posey, now a captain, was posted to the newly established Civil Affairs Center at Shrivenham, England, where he was assigned to the Civil Affairs Training School to await his next assignment. In early 1944, Posey was selected for MFA&A duty by its deputy chief, Col. Henry C. Newton, an architect from Los Angeles. Newton had found Posey’s name on a list of all architects on active duty from the American Institute of Architects. Posey was assigned as a Monuments Officer with Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army later that spring and arrived in Normandy, France, in July 1944.

As the Allies fought their way across France in the summer and fall of 1944, Posey was tasked with protecting and preventing further damage to war-ravaged cultural treasures along the Normandy coast. Posey did whatever he could to protect the bombed-out churches and cultural landmarks in the cities of Saint-Lô, Coutances, Saint-Malo, Les Iffs, and Rennes. But Posey and other MFA&A personnel were hampered by a lack of logistical support, such as transportation, and in many instances the most they could do was post “Off Limits” signs and move on.

In December 1944, Posey was joined in his efforts by Private First Class (PFC) Lincoln Kirstein, a Harvard graduate who would go on to a stellar career in the American arts world after the war, most notably as a co-founder of the New York City Ballet. Posey and Kirstein gathered information, located local artworks, and did their best to repair damaged buildings and monuments in the aftermath of the fighting while trying to prevent further destruction.

By happenstance, in March 1945 Posey was suffering from a toothache and the Army dentist was hundreds of miles away, so Kirstein located a dentist in the German city of Trier. Posey and Kirstein explained to the dentist that they were there to protect monuments and art, and he suggested they meet his son-in-law who was a major in the German Army and had the same job. After a long and harrowing ride through the German countryside they finally arrived at a forest cottage to meet the dentist’s son-in-law, Hermann Bunjes. Early in the war, Bunjes had worked for Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring and helped Göring remove private French artworks to Germany. A scholar of French Gothic sculpture and a fellow art lover, Bunjes felt comfortable divulging critical information about the art the Nazis had stolen in France and, more importantly, where it was hidden in a salt mine near the Austrian alpine village of Alt Aussee.

Posey and Kirstein arrived in Alt Aussee on May 12, 1945, less than a week after the war in Europe was declared over. They and some local miners cleared a small entrance to a mine, and the pair entered on May 13th. There, they found more than 6,500 paintings and many more drawings, prints, sculptures, and other objets d’art, including Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna, Vermeer’s The Astronomer, and Van Eyck’s The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb.

Robert Posey and Recovered Artworks

Considered a masterpiece of western art, the so-called Ghent Altarpiece is Belgium’s most important and beloved artistic treasure. Painted in the Northern Renaissance style, it was designed to be displayed behind the altar of Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium. It is a very large and heavy piece that consists of 12 painted, hinged panels and measures 11 by 15 feet when fully open. When the work is folded or closed, it depicts scenes from the biblical story of the Annunciation of Mary and images of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, among others. When expanded, the panels reveal paintings of the Holy Trinity, the Virgin Mary, and St. John the Baptist flanked by images of Adam and Eve, all overlooking another biblical scene—the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb—hence the piece’s name. Coveted by German dictator Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders, Belgian officials gave the piece to the Vichy French government for safekeeping in 1940. Hitler later learned of its location and in July 1942 ordered it taken to a hiding place within the German Reich. From mid-May 1945 up to his return to the United States later that fall, Posey oversaw the rescue of thousands of priceless works, including pieces by Vermeer, Raphael, Breughel, Titian, Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Michelangelo, Altdorfer, and Rubens as well as jewels belonging to the German Jewish Rothschild family of bankers. On August 21, 1945, the Ghent Altarpiece left Germany on a chartered flight accompanied only by Posey. Considered the most important piece of artwork stolen by the Germans, it was the first to be returned. For his efforts in rescuing these treasures, Posey was awarded the Order of Leopold from the Belgian government as well as named a Chevalier in the French Legion of Honor.

Robert Posey and Recovered Artworks

Considered a masterpiece of western art, the so-called Ghent Altarpiece is Belgium’s most important and beloved artistic treasure. Painted in the Northern Renaissance style, it was designed to be displayed behind the altar of Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium. It is a very large and heavy piece that consists of 12 painted, hinged panels and measures 11 by 15 feet when fully open. When the work is folded or closed, it depicts scenes from the biblical story of the Annunciation of Mary and images of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, among others. When expanded, the panels reveal paintings of the Holy Trinity, the Virgin Mary, and St. John the Baptist flanked by images of Adam and Eve, all overlooking another biblical scene—the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb—hence the piece’s name. Coveted by German dictator Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders, Belgian officials gave the piece to the Vichy French government for safekeeping in 1940. Hitler later learned of its location and in July 1942 ordered it taken to a hiding place within the German Reich. From mid-May 1945 up to his return to the United States later that fall, Posey oversaw the rescue of thousands of priceless works, including pieces by Vermeer, Raphael, Breughel, Titian, Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Michelangelo, Altdorfer, and Rubens as well as jewels belonging to the German Jewish Rothschild family of bankers. On August 21, 1945, the Ghent Altarpiece left Germany on a chartered flight accompanied only by Posey. Considered the most important piece of artwork stolen by the Germans, it was the first to be returned. For his efforts in rescuing these treasures, Posey was awarded the Order of Leopold from the Belgian government as well as named a Chevalier in the French Legion of Honor.

Lever House

Upon his honorable discharge from the U.S. Army, Posey resumed his family and professional life and settled in Scarsdale, New York, where he designed his own home. Posey enjoyed a fruitful career as an architect at the New York City branch of the international firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). One of the most significant designs he assisted with is the Lever House, located in mid-town Manhattan; with its notable open walk-ways and green space, it marked the transition for Park Avenue and Midtown Manhattan from a boulevard of masonry facades to one of glass towers. The building was constructed in 1952 as the headquarters for British soap company Lever Brothers. In 1982, the Lever House was designated as a New York City Landmark and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places the following year.

Lever House

Upon his honorable discharge from the U.S. Army, Posey resumed his family and professional life and settled in Scarsdale, New York, where he designed his own home. Posey enjoyed a fruitful career as an architect at the New York City branch of the international firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). One of the most significant designs he assisted with is the Lever House, located in mid-town Manhattan; with its notable open walk-ways and green space, it marked the transition for Park Avenue and Midtown Manhattan from a boulevard of masonry facades to one of glass towers. The building was constructed in 1952 as the headquarters for British soap company Lever Brothers. In 1982, the Lever House was designated as a New York City Landmark and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places the following year.

Posey was proud of his contributions to the war effort, but he rarely spoke about his experience. Nor did he keep in long-term contact with Lincoln Kirstein or any of the other MFA&A officers with whom he served. Although he left Alabama in 1929, family members have related that Posey was proud of his Alabama roots and always considered himself a southerner. Posey retired from SOM in 1974 and died on April 18, 1977, at the age of 73. On the day of his interment at Birmingham’s Elmwood Cemetery, the Belgian government sent a bouquet of flowers in gratitude to Posey for rescuing the Ghent Altarpiece.

Additional Resources

Edsel, Robert M., with Brett Witter. The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History. New York: Center Street, 2010.

Howe, Thomas C., Jr. Salt Mines and Castles: The Discovery and Restitution of Looted European Art. New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1946.

Kirstein, Lincoln. “The Quest for the Golden Lamb.” Town & Country September 1945.

Nicholas, Lynn H. The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

Plaut, James S. “Loot for the Master Race.” Atlantic Monthly 178 (September 1946): 57-63.

———. “Hitler’s Capital.” Atlantic Monthly 178 (October 1946): 73-78.

Posey, Robert K. “Protection of Cultural Materials During Combat.” College Art Journal 5 (January 1946): 127-31

Rorimer, James J. Survival: The Salvage and Protection of Art in War. New York: Abelard Press, 1950.