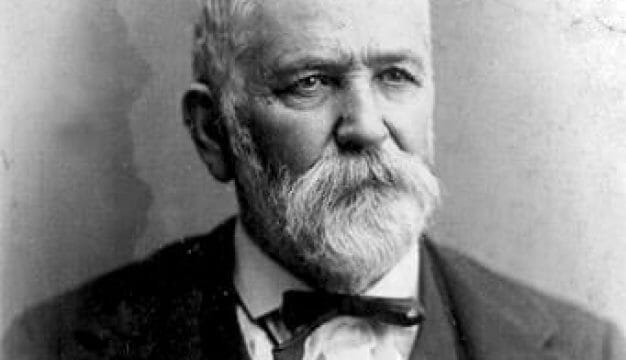

Gould Beech

Many historians and journalists today regard Gould Beech (1913-2000) as one of the most gifted and visionary journalists in Alabama during the twentieth century. His work for the Anniston Star, Montgomery Advertiser, and the Southern Farmer shed light on the racism and social injustice enshrined in Alabama’s political and legal culture. During his active years, however, he was attacked continuously by conservatives as a radical and a Communist, so much so that he gave up journalism and left Alabama for many decades.

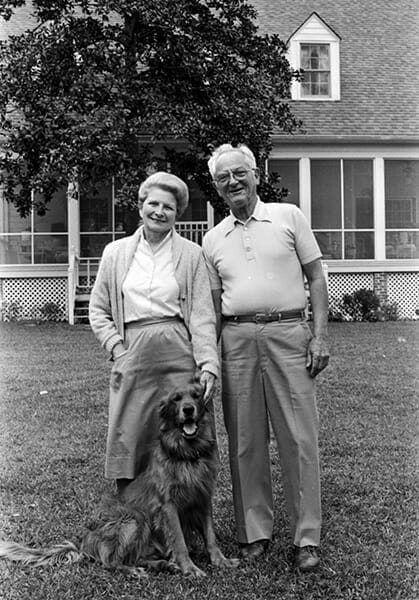

Gould and Mary Beech

Gould Means Beech was born May 5, 1913, in Florence, Lauderdale County, to James Ledbetter Beech and Lydia Means Gould Beech; he also lived in Foley and Montgomery. Beech had one sister and one half-sister from his father’s second marriage. His mother died when he was five years old; his father, a railroad conductor, witnessed the mistreatment of black workers on trains and was outspoken against the Ku Klux Klan. Beech majored in journalism at the University of Alabama, serving as editor of the UA student newspaper, the Crimson White. He studied under journalism professor Clarence Cason, whose controversial, ground-breaking book, 90 Degrees in the Shade, sharply criticized white southern society and helped form Beech’s determination to report honestly on racism and other social ills. During his time at UA, Beech began dating Mary Foster, whose relatives included a UA president; both had grandfathers in the university’s first class. Beech graduated in 1934, and the couple married in 1935. They would have two children.

Gould and Mary Beech

Gould Means Beech was born May 5, 1913, in Florence, Lauderdale County, to James Ledbetter Beech and Lydia Means Gould Beech; he also lived in Foley and Montgomery. Beech had one sister and one half-sister from his father’s second marriage. His mother died when he was five years old; his father, a railroad conductor, witnessed the mistreatment of black workers on trains and was outspoken against the Ku Klux Klan. Beech majored in journalism at the University of Alabama, serving as editor of the UA student newspaper, the Crimson White. He studied under journalism professor Clarence Cason, whose controversial, ground-breaking book, 90 Degrees in the Shade, sharply criticized white southern society and helped form Beech’s determination to report honestly on racism and other social ills. During his time at UA, Beech began dating Mary Foster, whose relatives included a UA president; both had grandfathers in the university’s first class. Beech graduated in 1934, and the couple married in 1935. They would have two children.

Beech had worked summers at the Anniston Star while still a student at UA and upon graduating was hired full-time by owner Col. Harry Ayers, whose father had founded the newspaper in 1899. The paper was, and is still, among the most liberal in the state. Grover Hall, legendary editor of the Montgomery Advertiser and the first Alabamian to receive a Pulitzer Prize, hired Beech as an associate editor at the Advertiser. Hall, who was famous for denouncing the Klan, anti-Semitism, and racial violence, was a powerful influence on Beech, who wrote similarly outspoken editorials about lynching, disfranchisement of blacks and poor whites, and the tenant farmer system. Beech left the Advertiser for a year in 1937 after winning a prestigious Julius Rosenwald Fellowship to the University of North Carolina, where he studied the negative effects on the democratic process of poor education and lack of voting rights among minorities.

Southern Farmer Printing Office

When World War II was declared, Beech served in Alaska and then Washington, D.C., where he was chief of the Information and Education Division of the U.S. Army’s Orientation Branch. During that time, he associated with a number of fellow liberal Alabamians of great political power, including Hugo Black, Clifford and Virginia Durr, Lister Hill, and Aubrey Williams. They exposed him to New Deal philosophies and deepened his interest in social justice and activism. When the war ended, Beech and Aubrey Williams moved to Montgomery to run the Southern Farmer, an agricultural weekly that had been purchased by liberal business mogul Marshall Field. Beginning in 1946, Beech wrote, under pseudonyms, all the copy for columns supposedly written by lonely hearts advisors, preachers, and agricultural experts. But he also editorialized boldly, under his own name, on eradicating the poll tax, organizing small farmers, and continuing New Deal programs that were being attacked as socialist.

Southern Farmer Printing Office

When World War II was declared, Beech served in Alaska and then Washington, D.C., where he was chief of the Information and Education Division of the U.S. Army’s Orientation Branch. During that time, he associated with a number of fellow liberal Alabamians of great political power, including Hugo Black, Clifford and Virginia Durr, Lister Hill, and Aubrey Williams. They exposed him to New Deal philosophies and deepened his interest in social justice and activism. When the war ended, Beech and Aubrey Williams moved to Montgomery to run the Southern Farmer, an agricultural weekly that had been purchased by liberal business mogul Marshall Field. Beginning in 1946, Beech wrote, under pseudonyms, all the copy for columns supposedly written by lonely hearts advisors, preachers, and agricultural experts. But he also editorialized boldly, under his own name, on eradicating the poll tax, organizing small farmers, and continuing New Deal programs that were being attacked as socialist.

Living and working in Montgomery, Beech became acquainted with gubernatorial candidate James E. “Big Jim” Folsom. Deeply admiring of Folsom’s progressive racial views, populist agenda, and willingness to go up against Alabama’s powerful business and agricultural interests, Beech took over Folsom’s rough-edged campaign, writing his speeches and arranging campaign appearances. He helped Folsom to a surprise win in 1946, but by then the men had made deep enemies of powerful steel, timber, and agricultural interests. In 1947, Beech left the Farmer after Folsom nominated him to the board of trustees of Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University). Folsom hoped that Beech would be able to counter what many saw as undue political control the conservative Alabama Farmers Bureau (now ALFA) wielded through the extension service agents in every county. After several weeks in which Beech was publicly denounced as a leftist, a Communist, and a dangerous radical who would bring New Deal governance to AU, Beech withdrew his name, instead accepting an appointment to the Alabama Beverage Control board.

The Beeches faced such continued hostility that, in 1950, they moved to Houston, Texas, where Beech worked with Houston mayor Roy Hofheinz, a wealthy liberal entrepreneur who owned a chain of radio stations. As his aide, Beech oversaw the quiet desegregation of the Houston public library system. He ran unsuccessfully for city commissioner, despite being endorsed by the Houston News, and both he and Mary Beech, who was equally involved in politics, worked on several campaigns, including helping future U.S. congresswoman Barbara Jordan become the first black woman elected to the Texas State Senate.

In the 1970s, the Beeches returned to Alabama, settling in the riverside community of Magnolia Springs in Baldwin County, where they had honeymooned. By then, newspaper reporters and historians had begun to recognize publicly Beech’s work for racial equality and fair treatment of the poor and underserved; many of his positions that once were called radical and Communist—desegregated schools and public facilities, voting rights and mandated protection of minorities against violence—had become mainstream. Days after casting his vote by absentee ballot in the first election of the new millennium and six months after Mary Beech’s death on July 10, Gould Beech died on November 5, 2000. He was inducted into the UA College of Communication and Information Sciences Hall of Fame in 2002.