Turpentine Industry in Alabama

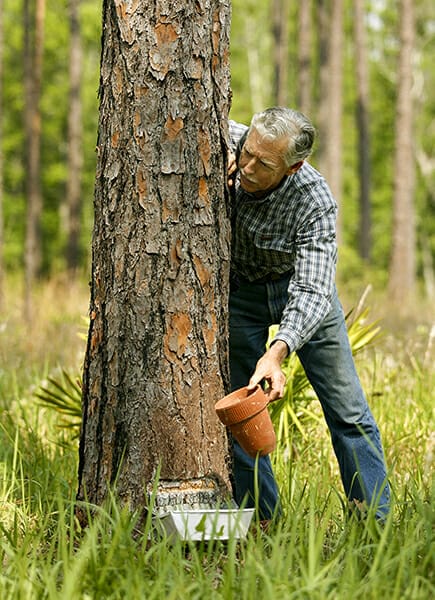

Sap Extraction Demonstration

The longleaf pine forests that once covered much of Alabama provided ample resources for the establishment and growth of the state’s turpentine industry. Between 1840 and 1930, turpentine distilling spanned Baldwin, Mobile, Washington, Choctaw, Escambia, and Tuscaloosa Counties. Turpentine was used primarily as a solvent and for fuel, and resin was used in the soap and varnish industries. This industry promoted economic development and industrial expansion, but it also had a history of exploitive labor practices, including forced labor by enslaved people, convicts, and immigrants. It was also known as the naval stores industry because pitch produced by the trees was used to caulk the seams of wooden sailing ships.

Sap Extraction Demonstration

The longleaf pine forests that once covered much of Alabama provided ample resources for the establishment and growth of the state’s turpentine industry. Between 1840 and 1930, turpentine distilling spanned Baldwin, Mobile, Washington, Choctaw, Escambia, and Tuscaloosa Counties. Turpentine was used primarily as a solvent and for fuel, and resin was used in the soap and varnish industries. This industry promoted economic development and industrial expansion, but it also had a history of exploitive labor practices, including forced labor by enslaved people, convicts, and immigrants. It was also known as the naval stores industry because pitch produced by the trees was used to caulk the seams of wooden sailing ships.

Some accounts suggest that turpentine harvesting began as early as 1777 in Mobile County, but significant numbers of operations did not arise in Alabama until the 1840s, after the widespread adoption of lightweight copper stills. Invented in 1834, these apparatuses reduced the cost of production because they could be set up near the harvesting site. Increased consumer demand for turpentine, pitch, and resin in the 1840s stimulated production. The growing rubber industry employed turpentine as a solvent and the expanding soap and varnish industries required resin for manufacturing. Consumers also purchased turpentine as a cheap alternative to oil for lamps.

In 1847, Col. R. D. James began a small-scale operation in Clarke County that by 1855 yielded 1,060,000 gallons of turpentine and 130,000 barrels of resin per year. Producers were attracted to the southern half of the state because of its largely untouched pine forests. Between 1850 and 1860, Alabama’s turpentine industry rapidly expanded, with the annual economic worth increasing 36 times, from $17,800 in 1850 to $642,000 by 1860.

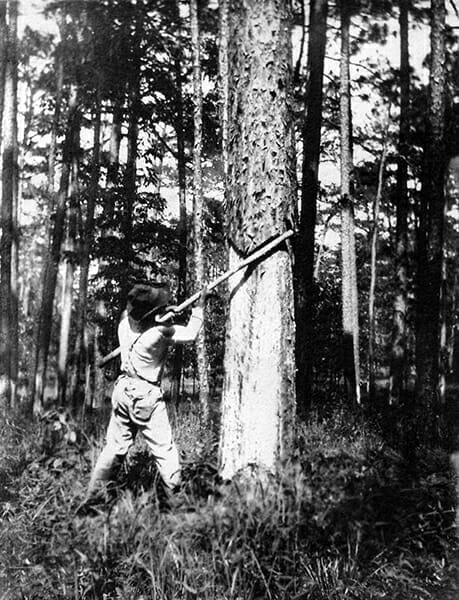

Turpentine Worker, 1908

Turpentine collection changed very little from its beginnings in the nineteenth into the early twentieth century. During the turpentine season, which lasted eight months, laborers extracted sap from longleaf pines in a three-step process. Beginning in November, workers entered the woods to begin “boxing” trees. Using long-headed axes, they cut a “box” into the base of the tree, ranging from approximately 10 to 14 inches wide and 2.5 to 3.5 inches deep, to catch the sap from the tree. After boxing was completed by the beginning of March, laborers chipped a “streak” approximately 2/3 of an inch wide and 1 inch deep above the box using a highly specialized tool called a “hack.” Chipping occurred weekly for 34 weeks and released the sap, which collected in the box. At the beginning of April, laborers began using a steel spatula to scoop the liquid (a drier, less viscous form of sap known as gum) from the box in a process called “dipping” and then deposited it in buckets. The gum was next transferred to 40-gallon barrels for transport to a distillery or to portable stills near the site. In addition to being labor intensive, this method of gathering the sap eventually killed the tree, with large stands of pines being depleted within a decade and forcing producers to move to new forests.

Turpentine Worker, 1908

Turpentine collection changed very little from its beginnings in the nineteenth into the early twentieth century. During the turpentine season, which lasted eight months, laborers extracted sap from longleaf pines in a three-step process. Beginning in November, workers entered the woods to begin “boxing” trees. Using long-headed axes, they cut a “box” into the base of the tree, ranging from approximately 10 to 14 inches wide and 2.5 to 3.5 inches deep, to catch the sap from the tree. After boxing was completed by the beginning of March, laborers chipped a “streak” approximately 2/3 of an inch wide and 1 inch deep above the box using a highly specialized tool called a “hack.” Chipping occurred weekly for 34 weeks and released the sap, which collected in the box. At the beginning of April, laborers began using a steel spatula to scoop the liquid (a drier, less viscous form of sap known as gum) from the box in a process called “dipping” and then deposited it in buckets. The gum was next transferred to 40-gallon barrels for transport to a distillery or to portable stills near the site. In addition to being labor intensive, this method of gathering the sap eventually killed the tree, with large stands of pines being depleted within a decade and forcing producers to move to new forests.

Turpentine Still in Calhoun County

Through the distillation process, operators transformed the gum into turpentine, pitch, and resin. Once the barrels reached the distillery, laborers transferred the gum to stills. Fires underneath the stills heated the gum and brought the mixture to boil. Vapor then flowed through a tube at the top of the still, where it condensed and dripped into another barrel. This mixture of turpentine and water then separated, and laborers skimmed the turpentine from the surface. This procedure, known as gum turpentining, took between three and a half to five and a half hours and produced both turpentine and resin.

Turpentine Still in Calhoun County

Through the distillation process, operators transformed the gum into turpentine, pitch, and resin. Once the barrels reached the distillery, laborers transferred the gum to stills. Fires underneath the stills heated the gum and brought the mixture to boil. Vapor then flowed through a tube at the top of the still, where it condensed and dripped into another barrel. This mixture of turpentine and water then separated, and laborers skimmed the turpentine from the surface. This procedure, known as gum turpentining, took between three and a half to five and a half hours and produced both turpentine and resin.

Many of the owners of turpentine operations in Alabama relocated from North Carolina, where forests had already been severely depleted. For example, James R. Grist purchased forestland in Mobile to expand his operation based in Beaufort County, North Carolina. In 1857, his cousin Benjamin Grist opened a turpentine plantation near the Fish River in Mobile County. The Grist venture in Alabama operated with enslaved labor and between 1859 and 1860 produced 26,337 barrels of sap that, after the distillation process, yielded 3,020 barrels of turpentine and 15,118 barrels of resin. Turpentine laborers endured some of the harshest conditions among southern industries. Although the enslaved laborers set the pace for boxing, chipping, and dipping, producers set enormous quotas that required high speed and skill.

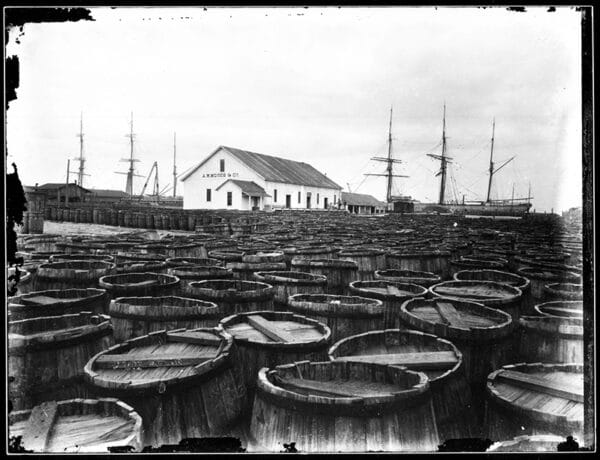

A. M. Moses Shipyard, Mobile

During the Civil War, poor market conditions and interrupted transportation temporarily halted naval stores production. But swift industrialization and the construction of numerous railroads after the war aided the industry’s recovery because new rail lines restored access to distilleries and opened up new areas for establishing additional distilleries. The industry faced several important changes after the war. The demise of enslaved labor resulted in a shortage of labor, as many freedpeople were unwilling to endure the harsh conditions of the industry. To remedy this situation, operators turned to leasing convicts from Alabama’s prison system and to a system known as debt peonage, in which indebted individuals were forced to work until a debt or loan was paid off. Distilleries in Tuscaloosa and Escambia counties leased state inmates to harvest gum in their pine tracts. Famed Alabama outlaw Railroad Bill likely escaped from a turpentining camp. Other distilleries hired northern labor agencies to procure white immigrant labor. These companies lured workers to Alabama with false promises of high wages and favorable working conditions, then essentially held laborers captive while they worked off their transportation costs. In 1902, for example, W. S. Harlan, the manager of Jackson Lumber Company’s mill in Lockhart, Covington County, was charged with perpetuating debt peonage and was convicted in 1906. Despite successful prosecution, debt peonage remained a staple of the South’s turpentine industry well into the 1920s.

A. M. Moses Shipyard, Mobile

During the Civil War, poor market conditions and interrupted transportation temporarily halted naval stores production. But swift industrialization and the construction of numerous railroads after the war aided the industry’s recovery because new rail lines restored access to distilleries and opened up new areas for establishing additional distilleries. The industry faced several important changes after the war. The demise of enslaved labor resulted in a shortage of labor, as many freedpeople were unwilling to endure the harsh conditions of the industry. To remedy this situation, operators turned to leasing convicts from Alabama’s prison system and to a system known as debt peonage, in which indebted individuals were forced to work until a debt or loan was paid off. Distilleries in Tuscaloosa and Escambia counties leased state inmates to harvest gum in their pine tracts. Famed Alabama outlaw Railroad Bill likely escaped from a turpentining camp. Other distilleries hired northern labor agencies to procure white immigrant labor. These companies lured workers to Alabama with false promises of high wages and favorable working conditions, then essentially held laborers captive while they worked off their transportation costs. In 1902, for example, W. S. Harlan, the manager of Jackson Lumber Company’s mill in Lockhart, Covington County, was charged with perpetuating debt peonage and was convicted in 1906. Despite successful prosecution, debt peonage remained a staple of the South’s turpentine industry well into the 1920s.

Another post-war change was the increased prominence of factors, persons whom today might be called agents or brokers. Although factorage houses (or, brokerages) had been a part of the turpentine industry since the early nineteenth century, factors played an increasingly important role after the war. In addition to buying and selling the products, they financed new operations through leasing forest tracts and furnishing supplies and equipment on credit. Located at the port of Mobile, Mobile County, Taylor, Lowenstein & Co. and the Alabama Naval Stores Co. bought, transported, and sold approximately 60,000 to 70,000 barrels of turpentine and 250,000 to 300,000 barrels of resin each year. In terms of dollar value of production, in 1870, Mobile County produced between $25,166 and $83,000 of tar and in 1880 between $60,001 and $116,200 of tar and turpentine; in 1870, Baldwin County produced between $180,671 and $407,102 and in 1880 between $162,301 and $416,641 of tar and turpentine; and in 1880 Washington Country produced between $60,001 and $116,200 of tar and turpentine.

Newport Turpentine and Rosin Company, 1956

In 1907, chemist Homer T. Yaryan developed a successful method for extracting turpentine and tar from charred longleaf pine stumps that brought additional changes to the industry. The new method of distillation consisted of heating small pieces of wood collected from pine stumps over a gas fire in a glass container known as a retort. After approximately 15 to 20 hours, the rosin separated and was collected from the bottom of the retort. This new method, coupled with increased financing opportunities, helped Alabama maintain its place, behind Florida and Georgia, as the third largest naval stores producer in the United States. Using the wood distillation method, between 1904 and 1909 Alabama produced 10 percent of all the turpentine and resin in the country. Alabama’s first major wood-processing plant opened in 1913, when Armin A. Schlesinger founded the Newport Turpentine and Rosin Company in Bay Minette, Baldwin County. By the 1930s, wood distillation had replaced the gum method, and Alabama successfully continued to produce turpentine and resin throughout the decade.

Newport Turpentine and Rosin Company, 1956

In 1907, chemist Homer T. Yaryan developed a successful method for extracting turpentine and tar from charred longleaf pine stumps that brought additional changes to the industry. The new method of distillation consisted of heating small pieces of wood collected from pine stumps over a gas fire in a glass container known as a retort. After approximately 15 to 20 hours, the rosin separated and was collected from the bottom of the retort. This new method, coupled with increased financing opportunities, helped Alabama maintain its place, behind Florida and Georgia, as the third largest naval stores producer in the United States. Using the wood distillation method, between 1904 and 1909 Alabama produced 10 percent of all the turpentine and resin in the country. Alabama’s first major wood-processing plant opened in 1913, when Armin A. Schlesinger founded the Newport Turpentine and Rosin Company in Bay Minette, Baldwin County. By the 1930s, wood distillation had replaced the gum method, and Alabama successfully continued to produce turpentine and resin throughout the decade.

Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, however, the supply of mature pine stumps had declined significantly, signaling the impending demise of the wood distillation method. Many Alabama plants were forced to close their doors, essentially ending the production of turpentine as a separate industry. At about the same time, the expanding pulpwood industry offered a new method of turpentine production that today is the primary way turpentine is produced. At pulpwood plants, pine trunks are stripped, then chipped and stewed in sulfuric acid to separate the cellulose (the organic material that gives plants structure) from the rest of the wood material. In addition to cellulose (used in many commercial and industrial applications), this process produces turpentine spirits and tall oil, a form of rosin used in the paper-making and as a drying agent in paint. When the turpentine spirits condense, they form sulfate turpentine, which is either recovered and sold or in some pulp and paper facilities is burned as a supplemental fuel. Restoration of the longleaf pine ecosystem is underway in several parts of the state.

Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, however, the supply of mature pine stumps had declined significantly, signaling the impending demise of the wood distillation method. Many Alabama plants were forced to close their doors, essentially ending the production of turpentine as a separate industry. At about the same time, the expanding pulpwood industry offered a new method of turpentine production that today is the primary way turpentine is produced. At pulpwood plants, pine trunks are stripped, then chipped and stewed in sulfuric acid to separate the cellulose (the organic material that gives plants structure) from the rest of the wood material. In addition to cellulose (used in many commercial and industrial applications), this process produces turpentine spirits and tall oil, a form of rosin used in the paper-making and as a drying agent in paint. When the turpentine spirits condense, they form sulfate turpentine, which is either recovered and sold or in some pulp and paper facilities is burned as a supplemental fuel. Restoration of the longleaf pine ecosystem is underway in several parts of the state.

Additional Resources

Gamble, Thomas. Naval Stores: History, Production, Distribution and Consumption. Savannah, Ga.: Review Publishing and Printing Company, 1921.

Outland, Robert B. III. Tapping the Pines: The Naval Stores Industry in the American South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004.

Powell, J. C. The American Siberia. Chicago: W. B. Conkey Company, 1893.