Fort Tombecbe

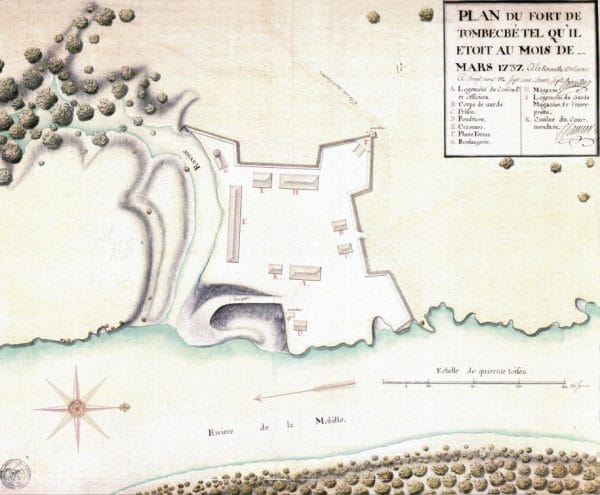

Fort Tombecbe, 1737

Fort Tombecbe (or Tombecbee), located near present-day Epes, Sumter County, was one of three major forts built by France in the early eighteenth century in Alabama. Like Fort Toulouse, Fort Tombecbe was established to protect France’s holdings from westward expansion by the British into the French colony of Louisiana. It also served as a trading post, solidifying France’s relations with the Choctaws, who were the most powerful French ally in the area, and was also held by the British and the Spanish during the colonial period. After being neglected for some time, the fort has been the focus of multiple archaeological excavations since the 1980s.

Fort Tombecbe, 1737

Fort Tombecbe (or Tombecbee), located near present-day Epes, Sumter County, was one of three major forts built by France in the early eighteenth century in Alabama. Like Fort Toulouse, Fort Tombecbe was established to protect France’s holdings from westward expansion by the British into the French colony of Louisiana. It also served as a trading post, solidifying France’s relations with the Choctaws, who were the most powerful French ally in the area, and was also held by the British and the Spanish during the colonial period. After being neglected for some time, the fort has been the focus of multiple archaeological excavations since the 1980s.

To help counter France’s lack of troops and population in its colonies, especially compared with the more numerous British colonials, the French established a chain of fortifications along waterways manned with small numbers of soldiers to solidify land claims and trade relations with local Native American groups. In January 1736, Joseph Christophe de Lusser, a Swiss captain in the service of the French Army, was recruited by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, governor of Louisiana, to begin construction of a fort along the Tombigbee River atop an 80-foot bluff to support his campaign against the Chickasaws the following year. When Bienville visited the site in April 1736, only part of the wooden palisade and one bread oven had been completed, so he remained at the fort to oversee construction before moving on to attack the Chickasaw. Tombecbe’s outline resembled that of a three-pointed star. Inside the red-cedar stockade walls stood nine buildings, including soldiers’ barracks, a powder magazine, a prison, and a storehouse to support the 30 to 50 soldiers stationed there.

Fort Tombecbe Monument

In May 1736, Bienville led an expedition of 600 soldiers and an equal number of Choctaw allies to attack the Chickasaws, who had become hostile to the French presence. His army was defeated by the Chickasaws: at the Battle of Ackia, near present-day Tupelo, Mississippi, on May 26. Work on Tombecbe continued at a slow pace and was not completed until the latter half of 1737, when it became a minor trading post for the Choctaw nation. Historical accounts suggest a Choctaw village existed near the fort, and some French soldiers and traders likely constructed homesteads outside the fort walls as well. Situated at such an advantageous location and far from any regular British force, the site was never attacked during the French and Indian War (1754-1763). The French surrendered the fort in November 1763 after ceding most of their territory in North America to Great Britain in the Treaty of Paris.

Fort Tombecbe Monument

In May 1736, Bienville led an expedition of 600 soldiers and an equal number of Choctaw allies to attack the Chickasaws, who had become hostile to the French presence. His army was defeated by the Chickasaws: at the Battle of Ackia, near present-day Tupelo, Mississippi, on May 26. Work on Tombecbe continued at a slow pace and was not completed until the latter half of 1737, when it became a minor trading post for the Choctaw nation. Historical accounts suggest a Choctaw village existed near the fort, and some French soldiers and traders likely constructed homesteads outside the fort walls as well. Situated at such an advantageous location and far from any regular British force, the site was never attacked during the French and Indian War (1754-1763). The French surrendered the fort in November 1763 after ceding most of their territory in North America to Great Britain in the Treaty of Paris.

British forces inspected Fort Tombecbe in 1763 and renamed it Fort York but did not continually inhabit the structure until 1766, when 21 men of the 21st Regiment arrived to help keep the peace between warring parties of Choctaw and Creeks. The fort’s remote location meant that the British had to provide troops there with frequent and large shipments of supplies, as detailed in the records kept by officers at the time. Thus, it must have been very costly for the French to maintain during their 26-year stay. After a truce between the Choctaw and Creeks in 1768, the British left the area, and Fort York was not occupied again by a European Army until the Choctaws ceded 25 acres of land to the Spanish in the 1792 Treaty of Boucfouca.

Fort Tombecbe Artifacts

When Spain took control of the fort in 1794, very little was left of the original structure. Instead of rebuilding another wooden fort, the Spanish constructed a smaller but more substantial earthen structure. The Spanish renamed the site Fort Confederacion (or Fort Confederation) in honor of their alliance with the local Native American groups, who were needed to protect Spanish territory from U.S. encroachment. Construction was finished by the end of 1795, and soon after, hostilities between the Chickasaw and Creek Indians and a territorial war with the United States increased the fort’s strategic importance. However, in 1797 the United States pressed enforcement of the land rights agreed upon in the Treaty of San Lorenzo, by which Spain had ceded all territory above the 31st parallel, including Fort Confederation, to the United States, thus marking the end of the European colonial era in Alabama. The area lay dormant until around 1815, when Col. George Strother Gaines established the Choctaw Trading House a few miles from the old fort site. It was partly established as a way for the United States to compensate the Choctaws for their support against the Creeks in the Creek War and operated until 1823.

Fort Tombecbe Artifacts

When Spain took control of the fort in 1794, very little was left of the original structure. Instead of rebuilding another wooden fort, the Spanish constructed a smaller but more substantial earthen structure. The Spanish renamed the site Fort Confederacion (or Fort Confederation) in honor of their alliance with the local Native American groups, who were needed to protect Spanish territory from U.S. encroachment. Construction was finished by the end of 1795, and soon after, hostilities between the Chickasaw and Creek Indians and a territorial war with the United States increased the fort’s strategic importance. However, in 1797 the United States pressed enforcement of the land rights agreed upon in the Treaty of San Lorenzo, by which Spain had ceded all territory above the 31st parallel, including Fort Confederation, to the United States, thus marking the end of the European colonial era in Alabama. The area lay dormant until around 1815, when Col. George Strother Gaines established the Choctaw Trading House a few miles from the old fort site. It was partly established as a way for the United States to compensate the Choctaws for their support against the Creeks in the Creek War and operated until 1823.

Although known to locals and honored with a monument by the Alabama chapter of the National Society of Colonial Dames in America in 1915, Fort Tombecbe was largely forgotten until 1980, when a team of archaeologists, sponsored by the Alabama Historical Commission and the University of West Alabama (UWA), began archaeological excavations. The dig uncovered artifacts from the French, British, and Spanish occupations, including musket balls, painted ceramics, glass bottle fragments and Choctaw pottery, which are curated by the Black Belt Museum in Livingston. Investigations in 2010 by UWA uncovered a portion of the stockade wall built by the French, a discovery that will enable researchers to orient future digs properly in the effort to find additional building foundations. Tombecbe’s existence covers all of early American history, from French colonial rule through early Alabama statehood and served thousands of people from diverse cultures. The owners of Fort Tombecbe, the University of West Alabama and the Archaeological Conservancy, hope that the site will become a park that the public can visit. For the immediate future, the site can only be viewed via special tour arranged with Black Belt Museum staff.

Further Reading

- Leach, Douglas Edward. Arms for Empire: A Military History of the British Colonies in North America, 1607-1763. New York: Macmillan Company, 1973.

- Parker, James W. “Archaeological Test Excavations at 1Su7: The Fort Tombecbe Site.” Journal of Alabama Archaeology 28(June 1982).

- Pate, James P. “The Fort of the Confederation: Spain on the Upper Tombigbee River.” Alabama Historical Quarterly 44 (Fall and Winter 1982): 171-86.