Oscar Underwood

Oscar Wilder Underwood (1862-1929) served Alabama for many years in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate. Known best for his extensive knowledge of and authorship of a sweeping tariff reform act, he was also a Democratic candidate for president in 1912 and in 1924, which saw the longest convention in U.S. history. He has been described as a conservative politician who opposed suffrage for women, Prohibition, and rights for organized labor.

Oscar W. Underwood

Underwood was born on May 6, 1862, in Louisville, Kentucky, the first of three boys born to Frederica Virginia Wilder and Eugene Underwood, son of Joseph Rogers Underwood, a U.S. representative and senator from Kentucky. It was the second marriage for both Virginia Wilder and Eugene Underwood, whose first wife, Catherine Thompson, died in 1857, leaving him with three boys. Oscar Underwood thus also had three older half-brothers from his father’s first marriage and a half-sister from his mother’s first marriage. Because of Underwood’s severe chronic bronchitis and his mother’s ailments, the family moved in 1865 to St. Paul, Minnesota. In that dry, cold climate, young Underwood spent much time outdoors and met such notable figures as U.S. Army generals George Custer and Winfield Scott as well as William “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

Oscar W. Underwood

Underwood was born on May 6, 1862, in Louisville, Kentucky, the first of three boys born to Frederica Virginia Wilder and Eugene Underwood, son of Joseph Rogers Underwood, a U.S. representative and senator from Kentucky. It was the second marriage for both Virginia Wilder and Eugene Underwood, whose first wife, Catherine Thompson, died in 1857, leaving him with three boys. Oscar Underwood thus also had three older half-brothers from his father’s first marriage and a half-sister from his mother’s first marriage. Because of Underwood’s severe chronic bronchitis and his mother’s ailments, the family moved in 1865 to St. Paul, Minnesota. In that dry, cold climate, young Underwood spent much time outdoors and met such notable figures as U.S. Army generals George Custer and Winfield Scott as well as William “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

When Underwood’s health improved, the family returned to Louisville, where, in 1879, he graduated with honors from Rugby, an exclusive private school. He then studied law at the University of Virginia, where he excelled in debating and was president of the Jefferson Society, a notable undergraduate honor. In October of either 1885 or 1886 Underwood married Eugenia Massie, with whom he had two sons. Eugenia died in 1900, and Underwood in 1904 married Bertha Woodward.

Underwood began his law practice in Minnesota but soon moved to the dynamic and rising southern industrial city of Birmingham, Jefferson County. His older brother William had settled there before him and touted the immense possibilities to be found in the city’s mining and manufacturing concerns. Oscar Underwood set up his law firm with James J. Garrett, developed several business interests, and became active in the Democratic Party.

Birmingham’s rapid growth earned Alabama an additional seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1892, and Jefferson County was joined with Bibb, Blount, Hale, and Perry Counties to form the Ninth District, with Underwood chairing the new district’s Democratic Committee. In 1894, Underwood entered the race for the new seat and won the primary against Louis Washington Turpin. He then faced Republican Truman H. Aldrich, a wealthy official of the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company, in the general election. Underwood waged an aggressive campaign, centering his attack on a Republican protective tariff that Aldrich favored. Underwood apparently won by the margin of 7,463 to 6,153, but Aldrich successfully contested the election and served out the latter part of Underwood’s term until March 1897.

Underwood won the subsequent election in 1896 and in Congress concentrated on tariff legislation, placing him in opposition to the protective tariff that had been a hallmark of Republicanism since the Civil War. Protective tariffs raise the cost of imports, thus making domestic goods cheaper by comparison. Underwood was neither devoted to free trade nor supportive of any particular industry or region but may have supported tariff reform out of a sense of fairness. Not until 1908, during Theodore Roosevelt’s administration, was a significant effort made on behalf of tariff reform. Underwood supported the Payne-Aldridge Tariff Act of 1909, although it was a compromise bill that disappointed progressives in both parties.

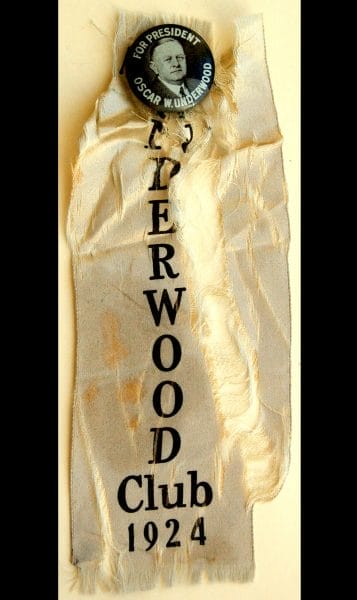

Oscar W. Underwood Campaign Ribbon

Underwood was nominated for president at the 1912 Democratic National Convention and received support from southern delegates, but he remained well behind frontrunners Woodrow Wilson and Champ Clark throughout the balloting. Wilson’s eventual election to the presidency finally gave Underwood his opportunity to promote more adequate tariff legislation. His positions from 1911 to 1915 as both House Majority Leader and chair of the powerful Ways and Means Committee gave him a strong voice. With Wilson’s support, Underwood began working in January 1913 on a new measure known as the “Underwood Tariff.” The bill easily passed the House during a special session of Congress in May. The Senate debated the language of the bill throughout the summer but left it substantially intact, and Woodrow Wilson signed it into law on October 3. The tariff lowered duties on 958 articles, raised 86, and left 307 unchanged. A key feature of the bill, designed to counter an anticipated reduction in revenue, reinstituted a graduated income tax of moderate rates. Unfortunately, the outbreak of World War I disrupted international trade and left economic conditions so chaotic that still another tariff bill was adopted when the Republicans regained power in 1920.

Oscar W. Underwood Campaign Ribbon

Underwood was nominated for president at the 1912 Democratic National Convention and received support from southern delegates, but he remained well behind frontrunners Woodrow Wilson and Champ Clark throughout the balloting. Wilson’s eventual election to the presidency finally gave Underwood his opportunity to promote more adequate tariff legislation. His positions from 1911 to 1915 as both House Majority Leader and chair of the powerful Ways and Means Committee gave him a strong voice. With Wilson’s support, Underwood began working in January 1913 on a new measure known as the “Underwood Tariff.” The bill easily passed the House during a special session of Congress in May. The Senate debated the language of the bill throughout the summer but left it substantially intact, and Woodrow Wilson signed it into law on October 3. The tariff lowered duties on 958 articles, raised 86, and left 307 unchanged. A key feature of the bill, designed to counter an anticipated reduction in revenue, reinstituted a graduated income tax of moderate rates. Unfortunately, the outbreak of World War I disrupted international trade and left economic conditions so chaotic that still another tariff bill was adopted when the Republicans regained power in 1920.

Rooster Auction

The death of Sen. Joseph Forney Johnston in 1913 paved the way for Underwood to run for that seat in 1914 against Rep. Richmond Pearson Hobson, a naval hero of the Spanish-American War and a staunch prohibitionist. Eloquent and handsome, Hobson, who had ousted Rep. John Bankhead from his House seat in 1906, accused Underwood of having ties to liquor interests. Underwood, who wanted counties to decide whether to prohibit alcohol sales, countered by attacking Hobson for supporting national women’s suffrage and direct popular election of the president. Both proposals, if adopted, he claimed, would dilute the South’s growing influence nationally. With Johnston’s son as his campaign manager, Underwood left the campaign in the hands of Alabama supporters and avoided confronting Hobson in open debate during his three campaign visits to the state. The strategy gave Underwood a convincing 89,470 to 54,738 victory.

Rooster Auction

The death of Sen. Joseph Forney Johnston in 1913 paved the way for Underwood to run for that seat in 1914 against Rep. Richmond Pearson Hobson, a naval hero of the Spanish-American War and a staunch prohibitionist. Eloquent and handsome, Hobson, who had ousted Rep. John Bankhead from his House seat in 1906, accused Underwood of having ties to liquor interests. Underwood, who wanted counties to decide whether to prohibit alcohol sales, countered by attacking Hobson for supporting national women’s suffrage and direct popular election of the president. Both proposals, if adopted, he claimed, would dilute the South’s growing influence nationally. With Johnston’s son as his campaign manager, Underwood left the campaign in the hands of Alabama supporters and avoided confronting Hobson in open debate during his three campaign visits to the state. The strategy gave Underwood a convincing 89,470 to 54,738 victory.

As senator from 1915-27, Underwood played a leading role in some of the major issues facing America in a crucial era. He was an influential member of the Appropriations Committee when huge war appropriations were made during World War I. He enthusiastically backed and spread progressive ideas regarding international alliances, such as the League of Nations, to promote better understanding among nations. These efforts were noticeably impeded when the Republicans regained the presidency and Congress in 1920, the same year he was reelected, defeating businessman Lycurgus Breckinridge “L. B.” Musgrove of Walker County. However, he served as minority leader in the Senate and was one of Pres. Warren G. Harding’s representatives to the Conference of the Limitations of Armament in 1921. It resulted in the Washington Naval Treaty, which limited the number and tonnage of large warships among the United States, Great Britain, France, Italy, and Japan.

Underwood may be best remembered for his role in the 1924 presidential campaign, which was both the pinnacle of his political career and opened the door for his eventual political demise. In January 1923, the Alabama legislature formally requested his presidential candidacy for the Democratic nomination. On July 31, Underwood addressed a joint session of the legislature. He was so heartened by the response that he announced for office the next day. This made him the first candidate to announce, 11 months before the national convention was held.

Underwood easily defeated L. B. Musgrove in Alabama’s Democratic presidential primary, 65,798 to 37,837, but he had little support in the rest of the South because of his strong anti-Klan stance and opposition to prohibition. Without this widespread support, few convention delegates attending the Democratic National Convention at Madison Square Garden in New York took his campaign seriously. His only hope lay in deadlocking the convention until enough votes drifted his way for the nomination. Indeed, Underwood, Gov. Alfred Smith of New York, and William G. McAdoo, the favorite of the prohibition supporters and Woodrow Wilson’s son-in-law, did deadlock. However, after 10 days and 103 ballots, the convention finally turned to a compromise candidate, John W. Davis of West Virginia.

By now state and national political trends were working dramatically against Underwood, and signs pointed to possible defeat had he stood for reelection in 1926. His opposition against the Klan and prohibition came at a time when those groups were politically strong in Alabama and the rest of the South. Moreover, influential Democratic senators, believing that Underwood had compromised himself by participating in Harding’s arms conference, prepared to contest his reelection as minority leader in the U.S. Senate. These warning signals made him decide against another bid for his Senate seat. For his stance against the Klan, Underwood later would be mentioned in future president John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage.

Underwood retired to his Virginia home, Woodlawn Plantation, which was part of the original estate of George Washington’s Mount Vernon. There, he turned his interest to writing. In 1928, he published his only book, The Shifting Sands of Party Polities. In December of that year, Underwood suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, followed by a paralyzing stroke two weeks; he died of complications on January 25, 1929. Although he had been an adopted Alabamian and had lived most of his political life elsewhere, Underwood stipulated that he be buried in Alabama. The Birmingham Special passenger train brought him back to Birmingham’s Elmwood Cemetery, and the Montgomery Advertiser eulogized him as “one of the great figures of latter day American politics.”

Further Reading

- Allen, Lee N. “The Underwood Presidential Movement of 1924.” Alabama Review 15 (April 1962): 83-99.

- ———. “Twenty-Four Votes for Oscar W. Underwood.” Alabama Review 48 (October 1995): 243-68.

- Johnson, Evans C. “Oscar W. Underwood: An Aristocrat from the Bluegrass.” Alabama Review 10 (July 1957): 184-203.

- ———. “Oscar W. Underwood: A Fledgling Politician.” Alabama Review 13 (April 1960): 109-26.

- ———. “Oscar W. Underwood and the Senatorial Campaign of 1920.” Alabama Review 21 (January 1968): 3-20.

- ———. Oscar W. Underwood, A Political Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1980.

- Torodash, Martin. “Underwood and the Tariff.” Alabama Review 20 (April 1967): 115-30.

- Underwood, Oscar W. The Shifting Sands of Party Polities. New York: The Century Company, 1931.