Avondale Mills

Avondale Mills

From its founding in 1897, textile manufacturing firm Avondale Mills left its mark on towns and cities throughout Alabama. Avondale Mills earned the respect of many mill workers for its Progressive Era programs for employees, and the disdain of reformers for its labor practices, particularly the use of child labor. Avondale Mills spanned the rise and fall of Alabama’s industrial history, and its most notable owners, the Comer family, became some of the most powerful people in the state. The company ceased operations in July 2006, unable to compete with foreign textile manufacturers and unable to recover from a tragic train accident next to its Graniteville, South Carolina, facility in 2005.

Avondale Mills

From its founding in 1897, textile manufacturing firm Avondale Mills left its mark on towns and cities throughout Alabama. Avondale Mills earned the respect of many mill workers for its Progressive Era programs for employees, and the disdain of reformers for its labor practices, particularly the use of child labor. Avondale Mills spanned the rise and fall of Alabama’s industrial history, and its most notable owners, the Comer family, became some of the most powerful people in the state. The company ceased operations in July 2006, unable to compete with foreign textile manufacturers and unable to recover from a tragic train accident next to its Graniteville, South Carolina, facility in 2005.

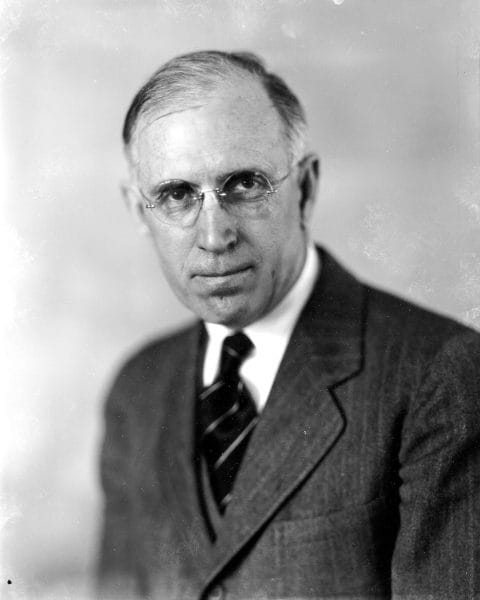

Braxton Bragg Comer

Around 1897, the Trainer family, which owned a textile business in Chester, Pennsylvania, began looking to expand its business into the South. It focused on the new and growing industrial city of Birmingham, Jefferson County, because of its proximity to inexpensive cotton sources and labor. In exchange for stock in the company, Frederick Mitchell Jackson Sr. and other Birmingham civic leaders agreed to invest $150,000 in private funding to build a mill. Jackson, president of Birmingham’s Commercial Club (a forerunner of the Birmingham Area Chamber of Commerce), pledged his help to increase employment in Birmingham. The Trainers accepted the pledge of financial assistance and sought an Alabamian to invest $10,000 in the project and assume presidency of the mill. In 1897, they approached Braxton Bragg Comer, a successful cotton farmer and businessman who wanted to support an industry that would employ both women and men in Birmingham.

Braxton Bragg Comer

Around 1897, the Trainer family, which owned a textile business in Chester, Pennsylvania, began looking to expand its business into the South. It focused on the new and growing industrial city of Birmingham, Jefferson County, because of its proximity to inexpensive cotton sources and labor. In exchange for stock in the company, Frederick Mitchell Jackson Sr. and other Birmingham civic leaders agreed to invest $150,000 in private funding to build a mill. Jackson, president of Birmingham’s Commercial Club (a forerunner of the Birmingham Area Chamber of Commerce), pledged his help to increase employment in Birmingham. The Trainers accepted the pledge of financial assistance and sought an Alabamian to invest $10,000 in the project and assume presidency of the mill. In 1897, they approached Braxton Bragg Comer, a successful cotton farmer and businessman who wanted to support an industry that would employ both women and men in Birmingham.

Comer accepted the Trainers’ offer and as president became the driving force behind Avondale Mills in its early years, even buying and weighing cotton and selling the final product, typically dyed and undyed cloth and yarn. (The Trainer family and other northern shareholders were bought out not long after Comer became president.)

In 1897, Comer built the first mill in the Birmingham neighborhood of Avondale, hence the name Avondale Mills. By 1898, Avondale Mills employed more than 400 people as spinners, weavers, and mechanics and generated $15,000 in profit. In 1906, B. B. Comer was elected governor of Alabama but remained president of the company, although he turned over its management to his son James McDonald (Donald) Comer. The following year, Avondale Mills declared $55,000 in profit and produced almost 8 million yards of material.

Avondale drew large numbers of poor Alabamians who were yearning for work. For many former sharecroppers and tenant farmers, both black and white, the steady paychecks and working hours were very appealing compared with life on the farm at a time when cotton prices were falling. A farm laborer who had been earning a potential $400.00 annually could work in a textile mill for a potential $700.00 annually. And with other family members working in the mill, family income rose accordingly.

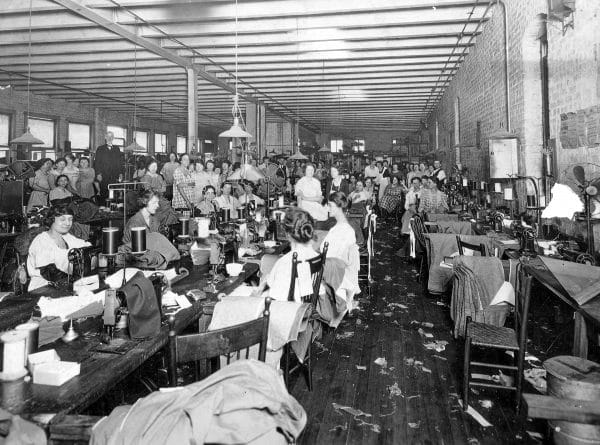

Child Workers at an Avondale Mill

Comer’s relationship to labor never progressed past his strong plantation-paternalism, an attempt to control almost every aspect of the mill worker’s life. He controlled their working conditions at the mill, and by providing housing, recreation, and places of worship, he controlled much of their private lives as well. One of Comer’s first initiatives was to provide a place of respite for all of his workers. He purchased land near Panama City, Florida, and created a beach-front park (now Camp Helen State Park) where members of the Comer family and Avondale workers could swim, boat, and fish. Later named Camp Helen, the park had a large central building with a number of scattered guest cottages. The mills closed at different times during the summer to allow employees to visit the camp. African American workers were also allowed separate time to use the facilities. Comer also established a kindergarten at the Birmingham mill that was directed by his daughters, Mignon, Catherine, and Eva. Comer’s daughters also taught elsewhere, including Sylacauga.

Child Workers at an Avondale Mill

Comer’s relationship to labor never progressed past his strong plantation-paternalism, an attempt to control almost every aspect of the mill worker’s life. He controlled their working conditions at the mill, and by providing housing, recreation, and places of worship, he controlled much of their private lives as well. One of Comer’s first initiatives was to provide a place of respite for all of his workers. He purchased land near Panama City, Florida, and created a beach-front park (now Camp Helen State Park) where members of the Comer family and Avondale workers could swim, boat, and fish. Later named Camp Helen, the park had a large central building with a number of scattered guest cottages. The mills closed at different times during the summer to allow employees to visit the camp. African American workers were also allowed separate time to use the facilities. Comer also established a kindergarten at the Birmingham mill that was directed by his daughters, Mignon, Catherine, and Eva. Comer’s daughters also taught elsewhere, including Sylacauga.

Despite the amenities B. B. Comer provided to his workforce, he and the company have been criticized for their extensive use of child labor in the mills and for opposing legislation to restrict such labor. One historian documented 187 children (out of 774 employees) ages 8 to 15 working in the Birmingham mill in 1900. Some families reluctantly allowed their children to be employed at the mill, but other families, which were accustomed to all members laboring on the farm, often welcomed the opportunity for their children to work and earn a paycheck. Comer claimed that families demanded their children have the opportunity to work; hence he simply responded to the will of his employees. Labor reformers noted that there were important differences between farm work and factory work. On the farm, children worked hard but at their own pace with no penalty for stopping. The relentless pace of the mill, however, endangered children because they often did not have the stamina or physical strength to work long hours. A misstep around a running machine was much more dangerous than getting tired in an open field. Also, even when children were employed to sweep the floors, a fairly safe activity, they were absent from school.

Donald Comer

When Donald Comer assumed management of Avondale Mills in 1907, he continued his father’s business success. He expanded the company into Sylacauga, building the Eva Jane plant in 1913. In 1919, he constructed Sallie B. No. 1 and Catherine Mills and completed Sallie B. No. 2 in 1926, although some sources state it was in 1922. Avondale plants often bore the name of women in the family: for example, the Eva Jane plant was named for B. B. Comer’s wife. Other plants carried the names of B. B. Comer’s children: Catherine, Sallie B., and later Mignon. These and other Avondale plants typically turned out rope, hosiery yarns, sheeting, indigo denims, and heavy twills.

Donald Comer

When Donald Comer assumed management of Avondale Mills in 1907, he continued his father’s business success. He expanded the company into Sylacauga, building the Eva Jane plant in 1913. In 1919, he constructed Sallie B. No. 1 and Catherine Mills and completed Sallie B. No. 2 in 1926, although some sources state it was in 1922. Avondale plants often bore the name of women in the family: for example, the Eva Jane plant was named for B. B. Comer’s wife. Other plants carried the names of B. B. Comer’s children: Catherine, Sallie B., and later Mignon. These and other Avondale plants typically turned out rope, hosiery yarns, sheeting, indigo denims, and heavy twills.

Donald Comer also began to reevaluate Avondale’s relationship with its work force and expanded on his father’s progressivism. Historians have noted that Donald had a more personal relationship with his employees and interest in their lives. He introduced a profit-sharing plan wherein profits were split between the company and employees. Each month, the employees received a check based on the profits from the previous 12 months. Donald Comer also prided himself on offering the same opportunities to African Americans at a time when racism was pervasive and institutionalized throughout the South; of the 8,500 people Avondale employed in 1947, 12 percent, or about 1,020 individuals, were African American.

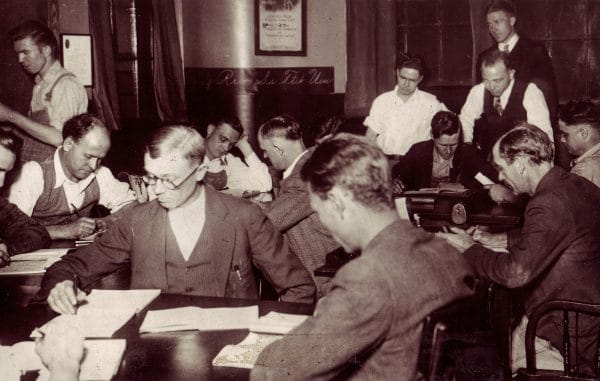

Avondale Night School

Known to mill workers as “Boss,” Donald Comer earned the appreciation of many workers, who were known as operatives, and his efforts generated a sense of pride in the Avondale Mills communities. The company’s arrival in Sylacauga, for example, was described by a local historian as the most important event in the town’s history, although Sylacauga had other industries, including Sylacauga Brick Yard and the Moretti-Harrah Marble Quarries. Avondale’s impact on Sylacauga was heightened by the presence of five plants in the county. The Catherine Central Plant and the Eva Jane Plant employed almost 3,000 people. Mill owners typically provided housing for workers and little else. Outhouses were often located between or behind the houses. Comer, however, located sanitation facilities inside and the company charged only $0.75 a week for housing out of a salary of $12.00 to $20.00 a week. The company built schools, which sometimes also welcomed children from the community, as well as churches. Mill operatives could live in the mill village, which had a dairy, a poultry farm, and other amenities. Bragg Comer, another of B. B. Comer’s sons, supervised the construction of Drummond Fraser Hospital, a 35-bed hospital for Avondale workers. At one point, Avondale even provided a canning plant, though employees had to pay for the cans. Avondale Mills also owned Camp Brownie on the Coosa River, which offered boating opportunities for employees and their families. Avondale paid its workers in cash, but operatives also could purchase company scrip. One dollar’s worth of scrip could be purchased for $0.80, giving operatives a 20-percent discount at the mill village store because its prices matched those in the downtown stores. Understanding the motivations for this largess is complicated. The Comer family certainly had economic motives for keeping labor contented. And programs designed for children may have really been directed at their parents in an attempt to keep parents happy with the care their children received. And although Donald Comer promoted his corporate welfare efforts to boost the public image of Avondale Mills, the results for the workers were often the same: affection for the Comer family and Avondale Mills.

Avondale Night School

Known to mill workers as “Boss,” Donald Comer earned the appreciation of many workers, who were known as operatives, and his efforts generated a sense of pride in the Avondale Mills communities. The company’s arrival in Sylacauga, for example, was described by a local historian as the most important event in the town’s history, although Sylacauga had other industries, including Sylacauga Brick Yard and the Moretti-Harrah Marble Quarries. Avondale’s impact on Sylacauga was heightened by the presence of five plants in the county. The Catherine Central Plant and the Eva Jane Plant employed almost 3,000 people. Mill owners typically provided housing for workers and little else. Outhouses were often located between or behind the houses. Comer, however, located sanitation facilities inside and the company charged only $0.75 a week for housing out of a salary of $12.00 to $20.00 a week. The company built schools, which sometimes also welcomed children from the community, as well as churches. Mill operatives could live in the mill village, which had a dairy, a poultry farm, and other amenities. Bragg Comer, another of B. B. Comer’s sons, supervised the construction of Drummond Fraser Hospital, a 35-bed hospital for Avondale workers. At one point, Avondale even provided a canning plant, though employees had to pay for the cans. Avondale Mills also owned Camp Brownie on the Coosa River, which offered boating opportunities for employees and their families. Avondale paid its workers in cash, but operatives also could purchase company scrip. One dollar’s worth of scrip could be purchased for $0.80, giving operatives a 20-percent discount at the mill village store because its prices matched those in the downtown stores. Understanding the motivations for this largess is complicated. The Comer family certainly had economic motives for keeping labor contented. And programs designed for children may have really been directed at their parents in an attempt to keep parents happy with the care their children received. And although Donald Comer promoted his corporate welfare efforts to boost the public image of Avondale Mills, the results for the workers were often the same: affection for the Comer family and Avondale Mills.

Mill Workers at Avondale

Many Avondale employees enjoyed the corporate welfare Avondale Mills offered, but difficult economic times often brought demands for more benefits. During the Great Depression, Alabama’s mill workers endured production cuts, plant closings, pay shortages, and shorter work days to counter declining prices. In 1933, when labor organizers started local unions in Birmingham, Comer called a meeting to remind his employees of the many benefits they received and to say unions were not necessary. Foremen took their cue from his speech and began removing unionists from their jobs. Meanwhile, textile workers in Alabama began walking out of mills in 1934, individually and collectively, as part of a larger effort to protest declining wages; as many as 23,000 of the state’s 40,000 textile workers may have participated. In July 1934, workers at the Birmingham, Stevenson, and Sylacauga plants walked off the job. Comer closed the plants and did not reopen them until Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt called on all employees to return to work.

Mill Workers at Avondale

Many Avondale employees enjoyed the corporate welfare Avondale Mills offered, but difficult economic times often brought demands for more benefits. During the Great Depression, Alabama’s mill workers endured production cuts, plant closings, pay shortages, and shorter work days to counter declining prices. In 1933, when labor organizers started local unions in Birmingham, Comer called a meeting to remind his employees of the many benefits they received and to say unions were not necessary. Foremen took their cue from his speech and began removing unionists from their jobs. Meanwhile, textile workers in Alabama began walking out of mills in 1934, individually and collectively, as part of a larger effort to protest declining wages; as many as 23,000 of the state’s 40,000 textile workers may have participated. In July 1934, workers at the Birmingham, Stevenson, and Sylacauga plants walked off the job. Comer closed the plants and did not reopen them until Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt called on all employees to return to work.

In its 109-year history, Avondale Mills expanded to include plants throughout Alabama. By the years 1947 and 1948, Avondale Mills had reached its apex with 7,000 employees. The plant’s production efforts consumed 20 percent of Alabama’s cotton crop. In 1951, Comer released control of Avondale Mills to James Craig Smith Jr. Later, Avondale branched out into Georgia and South Carolina.

In 1986, Walton Monroe Mills Inc. purchased Avondale Mills. The two companies operated separately but shared a board of directors. In 1993, the two merged to become Avondale Incorporated. Avondale Mills Inc. became a subsidiary of Avondale Incorporated. Three years later, Avondale acquired the textile assets of the Graniteville Company. Twelve years later, at Graniteville, in the early morning of January 6, 2005, a Norfolk Southern train went through a misaligned track switch at 50 miles per hour. The train hit a parked locomotive and launched 16 cars, including a tank car with 90 tons of chlorine, into a lot adjacent to Avondale Inc.’s data processing center. The tank ruptured and sent a vapor cloud through Graniteville and the mill. Five Avondale workers were killed and the chlorine gas destroyed computers and equipment. Avondale released 350 employees from the Graniteville facility.

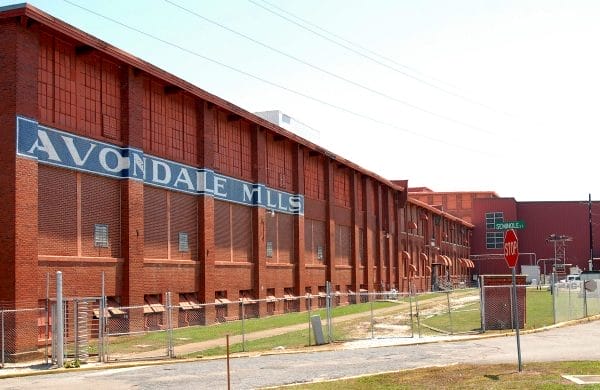

Avondale Mills, Sylacauga

Repercussions of the train wreck rippled throughout Avondale Mills until in July 2006, Avondale Incorporated ceased operations and sold three of its plants to Parkdale Mills Inc. Avondale closed three plants in Sylacauga and one plant each in Alexander City, Pell City, and Rockford, laying off more than 1,300 workers. The purchase by Parkdale Mills saved jobs in Alexander City and Rockford, but in January 2008, Parkdale closed its plant in Rockford. Overall, more than 4,000 workers in several states lost their jobs when Avondale shut down. Many of the workers affected by the layoffs have been eligible for federal job training and reemployment assistance. On June 22, 2011, the Avondale Mills Eva Jane plant building in Sylacauga caught fire and burned to the ground.

Avondale Mills, Sylacauga

Repercussions of the train wreck rippled throughout Avondale Mills until in July 2006, Avondale Incorporated ceased operations and sold three of its plants to Parkdale Mills Inc. Avondale closed three plants in Sylacauga and one plant each in Alexander City, Pell City, and Rockford, laying off more than 1,300 workers. The purchase by Parkdale Mills saved jobs in Alexander City and Rockford, but in January 2008, Parkdale closed its plant in Rockford. Overall, more than 4,000 workers in several states lost their jobs when Avondale shut down. Many of the workers affected by the layoffs have been eligible for federal job training and reemployment assistance. On June 22, 2011, the Avondale Mills Eva Jane plant building in Sylacauga caught fire and burned to the ground.

Further Reading

- Brannon, Peter A. “Donald Comer, Dean of the Alabama Textile Industry.” The Cotton History Review 3 (July 1960): 119-121.

- Breedlove, Michael. “Donald Comer: New Southerner, New Dealer.” Ph.D. diss., American University, 1990.

- Buechler, Joseph P. “Avondale Mills: The First Fifty Years.” Honors thesis, Auburn University, 1985.

- Comer, Donald. Braxton Bragg Comer (1848-1927) An Alabamian Whose Avondale Mills Opened New Paths for Southern Progress. New York: The Newcomen Society of England, 1947.

- Irby, William G. “The Avondale Mills of Alabama and Georgia.” Textile History Review 3 (October 1962): 197-204.

- Lathrop, Sallie B. Comer. My Mother. Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Printing Company, ca. 1940.

- ———. The Comer Family Goes To Town, Vol. II. Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Printing Company, 1942.

- ———. The Comer Family Grows Up, Vol. III. Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Printing Company, 1945.

- Salmond, John A. The General Textile Strike of 1934: From Maine to Alabama. Columbia, Mo.: University of Missouri Press, 2002.

- Smith, J. Craig. Avondale’s Third Generation. New York: Newcomen Society of England, 1972.