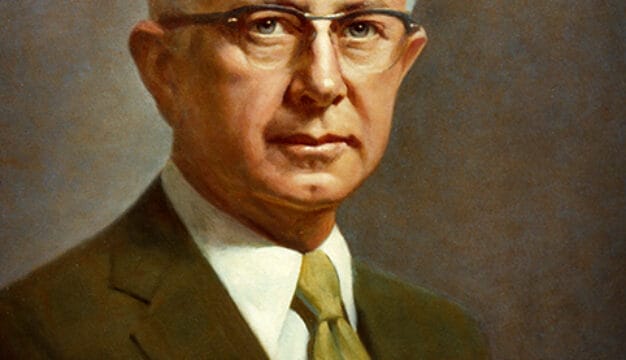

Robert M. Patton (1865-67)

Robert M. Patton

Robert Miller Patton (1809-1885) was inaugurated as governor of Alabama on December 13, 1865, only eight months after the Civil War ended. The popularly elected Patton succeeded Lewis E. Parsons, a Republican who had been appointed provisional governor. During Patton’s tenure, the U.S. Congress refused to seat congressmen from former Confederate states, leaving Alabama with no representation in the federal government. When Patton left office two years later, Alabama was poised to resume its place in the Union and was on a more solid financial footing.

Robert M. Patton

Robert Miller Patton (1809-1885) was inaugurated as governor of Alabama on December 13, 1865, only eight months after the Civil War ended. The popularly elected Patton succeeded Lewis E. Parsons, a Republican who had been appointed provisional governor. During Patton’s tenure, the U.S. Congress refused to seat congressmen from former Confederate states, leaving Alabama with no representation in the federal government. When Patton left office two years later, Alabama was poised to resume its place in the Union and was on a more solid financial footing.

Robert Patton was born on July 10, 1809, in Virginia, but spent almost his entire childhood in Alabama’s Tennessee Valley at Sweetwater, near Florence, Lauderdale County. He was educated at Green Academy in Huntsville. In 1829, Patton moved to Florence, where he became a merchant and a plantation owner, soon accumulating more than 4,000 acres of land and 300 enslaved people. In 1832, he married Jane Locke Braham, with whom he would have nine children. That same year, Patton ran successfully as a Whig candidate for a seat in the Alabama state legislature. He would serve in both the House and the Senate and was twice elected president of the Senate.

An opponent of secession, Patton voted for Democrat Stephen A. Douglas in the presidential election of 1860. Yet, as with many other reluctant Confederates, he supported Alabama’s course after the conflict began. Three of Patton’s sons served with Confederate military forces, and two of them were killed. At war’s end, Patton resumed his public career and helped draft the new state Constitution. In November 1865, Patton easily defeated two opponents in the federally mandated governor’s election and became the state’s 20th governor. His most pressing task involved restoring order and a measure of prosperity in a state that had little of either. In Alabama, as in every southern state, despair and adversity prevailed. Farms lay in ruins and livestock had disappeared. Freedmen were reluctant to enter into labor contracts with landowners, who generally offered inadequate compensation. The severe economic realities offered few industrial alternatives to an overwhelmingly agricultural state like Alabama. In his inaugural address, Patton acknowledged that the state’s economic circumstances were “peculiarly embarrassing,” although fertile land remained, and he reminded them of cotton’s continued value to the world.

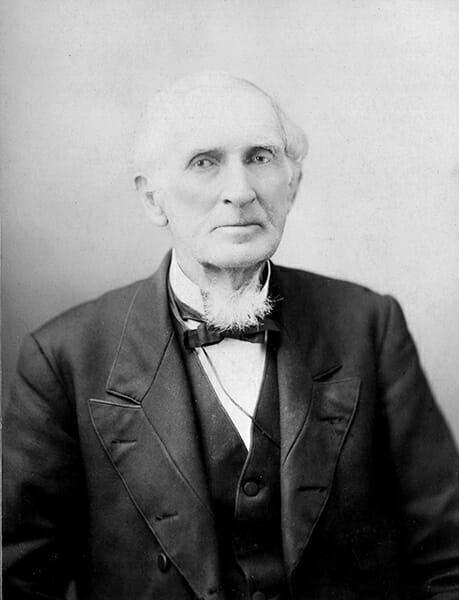

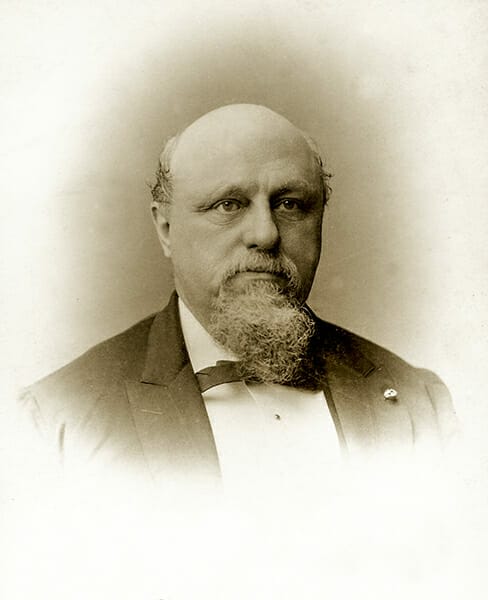

Wager Swayne

Although most white Alabamians accepted the Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery, they opposed extending the privileges of citizenship to blacks, as demanded by congressional Republicans. Patton resisted black enfranchisement and frequently expressed white supremacist views, thus maintaining support among white voters. While in office, Patton received countless plaintive appeals from desperate Alabamians. Foreclosures were rampant and families were losing their homes and land at sheriff sales in alarming numbers. He supported relief legislation and urged the legislature to find a compromise between creditors and debtors that protected the rights of both. Patton also cooperated with Brig. Gen. Wager T. Swayne, commissioner of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) for Alabama, in its work to feed, clothe, and provide subsistence for freed blacks and destitute whites during this critical period. Patton urged repeal of the federal cotton tax—$0.03 on every pound of processed cotton—on the grounds that it was crippling one of the state’s few sources of income and cited the lack of representation in Congress as an additional burden. Patton’s outcries brought little response, but the tax was discontinued in 1868 in response to protests from poor black cotton farmers.

Wager Swayne

Although most white Alabamians accepted the Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery, they opposed extending the privileges of citizenship to blacks, as demanded by congressional Republicans. Patton resisted black enfranchisement and frequently expressed white supremacist views, thus maintaining support among white voters. While in office, Patton received countless plaintive appeals from desperate Alabamians. Foreclosures were rampant and families were losing their homes and land at sheriff sales in alarming numbers. He supported relief legislation and urged the legislature to find a compromise between creditors and debtors that protected the rights of both. Patton also cooperated with Brig. Gen. Wager T. Swayne, commissioner of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) for Alabama, in its work to feed, clothe, and provide subsistence for freed blacks and destitute whites during this critical period. Patton urged repeal of the federal cotton tax—$0.03 on every pound of processed cotton—on the grounds that it was crippling one of the state’s few sources of income and cited the lack of representation in Congress as an additional burden. Patton’s outcries brought little response, but the tax was discontinued in 1868 in response to protests from poor black cotton farmers.

One of Patton’s highest priorities was putting Alabama’s finances in order. He succeeded in lowering the state’s debt and steered a responsible financial course. In the years preceding the war, railroad construction increased. Patton also strongly supported using state credit to subsidize and underwrite land grants and generous tax and incorporation laws to encourage renewed railroad construction in the state. Corrupt implementation of that policy, however, caused enormous economic problems for the state.

A statewide system of public education was just beginning at the war’s onset, and Patton urged state financial assistance in counties where funds were not available. He also promoted increased support for the Alabama Insane Hospital in Tuscaloosa. Patton earned the dubious distinction of ushering in the state’s convict-lease system, spurred by the idea of saving the state money by leasing prisoners in the state penitentiary to private interests. In these and other ways, Patton created the political landscape that would come to characterize Alabama well into the future. He assumed a classic paternalistic attitude toward the more than 437,000 emancipated slaves. Significantly, he vetoed Black Code legislation that would have limited the ability of African Americans to move residences and in other ways discriminated against freedpeople. He also advocated opening the hospital for the insane to black patients, as well as white, and he promoted the education and welfare of blacks. But, like most white Alabamians, he viewed them as incapable of participating equally in the state’s political and economic life.

In 1866, Congress began to require southern states to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment as a condition for readmission to the Union. The amendment created a common national citizenship regardless of a person’s race and extended to all Americans the guarantees of “due process” and “equal protection” of the law in the state of their residence and the nation as a whole. At first, Patton advised against ratification. Soon, however, he changed his mind, realizing that Alabama’s readmission to Congress would depend on compliance. With the anti-Reconstruction Pres. Andrew Johnson urging non-ratification, however, Alabama’s legislature ignored Patton’s logic and declined to ratify the amendment.

In March 1867, Congress, over President Johnson’s protests, passed the Military Reconstruction Act and took over the reconstruction process. Thus Patton remained governor in name only, and real power was effectively transferred to Swayne, with whom Patton enjoyed a cordial and workable relationship. The measure divided the South into military districts, with Alabama, Georgia, and Florida composing the Third District. Additionally, Congress officially made ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment a requirement for the end of military rule and readmission to the Union.

Patton served as governor of Alabama during one of its most critical and uncertain periods, and he worked to improve its financial outlook and infrastructure as much as possible, given the circumstances. Upon leaving the governor’s office, Patton was free to pursue various business ventures, and he promoted and invested in railroad development and served as trustee of several state colleges. Patton never approved of the subsequent Republican administration and lived to see it replaced by the conservative Democrats who would dominate state politics for the next century. Patton’s administration was a bridge between a turbulent social, political, and economic period to restoration within the Union. He died on February 29, 1885, at age 75 at his Sweetwater home and was buried at Maple Hill Cemetery in Huntsville.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Carter, Dan T. When the War Was Over: The Failure of Self-Reconstruction in the South, 1865-1867. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1985.

- Rogers, William Warren et al. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.

- Summers, Mark W. Railroads, Reconstruction, and the Gospel of Prosperity Aid Under the Radical Republicans: 1865-1877. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk. The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865-1881. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1991.