Hunting in Alabama

White-tailed Buck

Hunting remains one of Alabama‘s strongest links to its rural past and is a major source of recreation for its citizens. Deer and turkey populations in the state are estimated to be at near pre-European settlement levels, and large tracts of land are available for hunting leases. Although quail, dove, rabbit, and migratory bird habitats have been altered throughout the state’s history, these game animals still exist in “huntable” numbers, that is, there is a population large enough to allow properly regulated hunting, affording people ample opportunity to participate in the sport. According to the most recent statistics, hunting brought in more than $1.2 billion in revenue. The state supports the activity mostly through its Wildlife Management Areas and to a lesser extent in selected nature preserves and recreation areas.

White-tailed Buck

Hunting remains one of Alabama‘s strongest links to its rural past and is a major source of recreation for its citizens. Deer and turkey populations in the state are estimated to be at near pre-European settlement levels, and large tracts of land are available for hunting leases. Although quail, dove, rabbit, and migratory bird habitats have been altered throughout the state’s history, these game animals still exist in “huntable” numbers, that is, there is a population large enough to allow properly regulated hunting, affording people ample opportunity to participate in the sport. According to the most recent statistics, hunting brought in more than $1.2 billion in revenue. The state supports the activity mostly through its Wildlife Management Areas and to a lesser extent in selected nature preserves and recreation areas.

Alabama’s extremely diverse physiography ranges from the Appalachian Mountains in the north to coastal marshes and beaches in the south. This wide range of physical environments creates a variety of hunting opportunities and lends itself to a range of methods. People of many social, economic, and ethnic backgrounds enjoy the pastime, although white men who live in small towns or rural areas make up majority of hunters in Alabama. Deer hunting during the fall and winter and turkey in the spring are the most common activities.

Early Practices

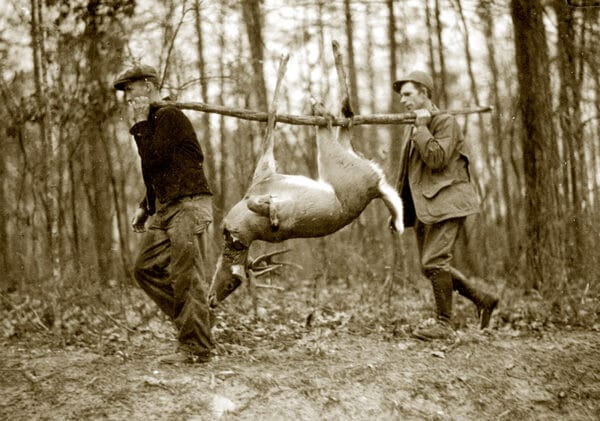

Alabama Deer Hunters

Native Americans in Alabama hunted elk (long since eradicated from the state by overhunting), bear, small game, and some fowl, but their main quarry was white-tailed deer. After they acquired firearms, they joined with their colonial counterparts in killing the animals for the deerskin trade, often leaving the meat to rot. During the eighteenth century, European trappers and market hunters made forays into Alabama, taking game for food and sale. But extensive hunting by Europeans did not occur until settlers began moving into the state around the beginning of the nineteenth century. Early settlers used flintlock rifles, ranging from .36 to .45 caliber, and smoothbore flintlock fowling pieces. The rifles fired single-round balls from a grooved barrel; a fowling piece was an early shotgun that had no rifling and fired multiple projectiles, or shot, that varied in size from .33-caliber buckshot to tiny birdshot.

Alabama Deer Hunters

Native Americans in Alabama hunted elk (long since eradicated from the state by overhunting), bear, small game, and some fowl, but their main quarry was white-tailed deer. After they acquired firearms, they joined with their colonial counterparts in killing the animals for the deerskin trade, often leaving the meat to rot. During the eighteenth century, European trappers and market hunters made forays into Alabama, taking game for food and sale. But extensive hunting by Europeans did not occur until settlers began moving into the state around the beginning of the nineteenth century. Early settlers used flintlock rifles, ranging from .36 to .45 caliber, and smoothbore flintlock fowling pieces. The rifles fired single-round balls from a grooved barrel; a fowling piece was an early shotgun that had no rifling and fired multiple projectiles, or shot, that varied in size from .33-caliber buckshot to tiny birdshot.

Dove Hunting in Dallas County

Deer, rabbits, squirrels, raccoons, and upland birds and waterfowl supplemented a diet that relied heavily on salt pork, but because these animals also damaged crops and gardens, they were frequently shot as pests. In its earliest years, hunting was recreational, but its role in providing protein created a strong ethic among Alabama hunters to eat what they killed that remains prevalent today.

Dove Hunting in Dallas County

Deer, rabbits, squirrels, raccoons, and upland birds and waterfowl supplemented a diet that relied heavily on salt pork, but because these animals also damaged crops and gardens, they were frequently shot as pests. In its earliest years, hunting was recreational, but its role in providing protein created a strong ethic among Alabama hunters to eat what they killed that remains prevalent today.

Subsistence, or “meat hunters,” frequently did far more damage to game populations than sport hunters. Early subsistence hunters hunted year-round, without regard for breeding seasons or age or sex of the quarry. Motivated by profit, market hunters throughout the nineteenth century relentlessly pursued deer, whose hides were prized for leather, and nearly drove them to extinction.

Hunting patterns and practices were further altered by white settlers and enslaved workers, who transformed Alabama’s landscape into vast acres of cultivated fields. Most people made their living as small farmers. Their primary income came from hogs marked by the owner and turned loose in the woods, where they competed with wildlife for food, a practice that was detrimental to the deer and turkey populations. Large-scale agriculture also put pressure on habitats as farmers and slaves cleared land to grow cotton. By 1900, with 4 million acres of Alabama land in cotton production and millions more in hay and corn production, Alabama’s deer and turkey populations had been squeezed into narrow bands of woods along its river systems. At its low ebb, the deer population plummeted to about 5,000 animals, mostly in the Alabama and Tombigbee river bottoms.

Small Game and Birds

Open, cultivated land made poor deer and turkey habitat, but it created excellent habitat for bobwhite quail, mourning doves, and eastern cottontail rabbits. Common plowing practices left wide fence rows next to the field, which were ideal habitat for quail and rabbits, as were fallow fields. Doves thrived in oat and corn fields and in the feed lots where draft animals ate. Plantation owners mimicked their European counterparts by using pointing dogs to hunt quail, which freeze until the hunter almost steps on them. This type of hunting was particularly well suited to the muzzle-loading, black-powder fowling pieces, with their very limited ranges of 35 to 40 yards. A planter would frequently ride on a horse while a servant walked beside him and held the horse’s reins; the hunter thus could dismount quickly when the dog pointed.

Quail Hunter in Mobile County

Changing farming practices and habitats have caused quail numbers to decline drastically. Farmers have planted pasture grasses that aren’t suitable for quail and the number of animals that eat quail eggs, such as raccoons, opossums, skunks, and snakes, has increased rapidly. Today, there is virtually no suitable quail habitat left in Alabama. Quail hunting mostly takes place on shooting preserves, where pen-raised birds are released during organized hunts.

Quail Hunter in Mobile County

Changing farming practices and habitats have caused quail numbers to decline drastically. Farmers have planted pasture grasses that aren’t suitable for quail and the number of animals that eat quail eggs, such as raccoons, opossums, skunks, and snakes, has increased rapidly. Today, there is virtually no suitable quail habitat left in Alabama. Quail hunting mostly takes place on shooting preserves, where pen-raised birds are released during organized hunts.

Southern planters again imitated European gentry when hunting doves, stationing themselves around a corn or oat field that was attracting the birds and firing at them as they flew into the field. Dove shoots became great social events, and hosts often treated guests to a barbecue, a tradition that continues today. The dove population, however, has slumped drastically with the disappearance of open land and declining grain production.

Rabbits were the quarry of choice for the state’s poorer residents, particularly the enslaved. Many slaves were trusted with firearms and allowed to hunt; archaeological digs have uncovered gun parts in slave quarters and the bones of small game such as rabbits and squirrels. Slaves, and freed blacks up through the 1930s, often employed the “tap stick,” which worked similarly to the Australian boomerang. It was a stick, weighted at one end, that twirled when thrown. The spinning motion allowed the weapon to sweep in a wider path than a rock thrown at a target and gave the thrower a greater probability of hitting the quarry. Slaves also found it effective to hunt rabbits in teams of eight to ten men with shotguns and a pack of beagles. Many white hunters also hunted with beagle packs, and rabbit hunting became one of the few social forums in which blacks and whites mingled freely.

Alabama Duck Hunting

Although Alabama is not noted for large concentrations of waterfowl, duck hunting is a part of the hunting culture. Wood ducks are a native species and are found throughout the state’s backwaters. The Mobile Delta served as a wintering ground for puddle ducks, such as gadwall and mallard. Diving ducks, such as canvasback, redhead, and ringneck, winter in the open bay. Early hunting was done from small boats push-poled through the tidal flats or sneak boats sculled through the open water. Later methods involved the use of blinds and decoys.

Alabama Duck Hunting

Although Alabama is not noted for large concentrations of waterfowl, duck hunting is a part of the hunting culture. Wood ducks are a native species and are found throughout the state’s backwaters. The Mobile Delta served as a wintering ground for puddle ducks, such as gadwall and mallard. Diving ducks, such as canvasback, redhead, and ringneck, winter in the open bay. Early hunting was done from small boats push-poled through the tidal flats or sneak boats sculled through the open water. Later methods involved the use of blinds and decoys.

As logging moved into the region, many of the hollow hardwood trees in which wood ducks nested were removed, driving the population into decline throughout the early twentieth century. Nesting-box programs and stream bank protection, along with strict bag limits, have helped the population recover. The establishment of the Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge in 1938 helped create large concentrations of waterfowl in the Tennessee Valley.

Squirrels were once the most popular game animal in Alabama, with more than 100,000 hunters pursuing them in the 1960s. Now, the state estimates that there are only about 25,000 squirrel hunters.

Deer and Turkey

Until the early twentieth century, all deer had been fair game for hunters, but biologists convinced hunters to shoot only bucks with antlers visible above the hairline. One buck can father many fawns in a season, but a doe can bear only one fawn or one set of twins a year. Thus, the key to rebuilding the population was to leave the does and shoot only bucks.

The deer drive became the standard way to hunt deer during the first half of the twentieth century. Hunters armed with shotguns loaded with buckshot stood several hundred yards apart in a line, usually along a road or railroad bed. Drivers or beaters and large deer hounds walked through the woods toward the hunters, yelling and beating on metal buckets or pans to push the deer toward the hunters, who shot as the deer ran past. Such communal hunts led to the formation of hunting clubs, which leased land from timber companies. Deer drives became social events with a breakfast or lunch on the hunting club property; meat from the hunt was divided among all participants. Hunters embraced the bucks-only principle for deer hunting and applied the same principle to turkeys, shooting only males, known as gobblers.

Changes in land use have greatly stimulated deer and turkey populations. A switch from cotton to soybeans created a high-protein source of food for deer. When soybean prices collapsed in 1980, much open agricultural land returned to woodlands. Also, areas clear cut by paper companies turned into thick undergrowth, which provides ideal habitat for deer for years. By 1970, conservation officials estimated the deer population at 400,000 and the turkey population at 200,000. The turkey population has since doubled, and the deer population stands at an estimated 1.6 million.

Changing Practices

Hound Dogs

In recent decades, fewer hunters pursue deer with drivers, dogs, and shotguns. Most prefer to cultivate small patches of cool-weather grasses and clovers to attract the deer and hunt from blinds or tree stands using high-powered rifles with telescopic sights, a practice known as food-plot hunting. The change has led to a rise in smaller hunting clubs that divide the land into areas where hunters are expected to stay while they hunt. This development has created conflict between the stationary food-plot hunters and the remaining drive hunters. The Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources has outlawed hunting deer with dogs in some areas as a result of the conflict. Whereas hunters once pursued a variety of game, food-plot hunting has created a deer-hunting monoculture. Hunters typically plant food plots for deer in September instead of going dove hunting. In mid-October, they begin hunting deer with bow and arrow when the state’s archery deer season opens, rather than hunt squirrels. A week-long muzzle-loader season in mid-November precedes the season for modern firearms that lasts until the last week of January, when many hunters used to shoot ducks. Few hunters now aim for quail and rabbit in February, choosing to take a break until turkey season begins in mid March.

Hound Dogs

In recent decades, fewer hunters pursue deer with drivers, dogs, and shotguns. Most prefer to cultivate small patches of cool-weather grasses and clovers to attract the deer and hunt from blinds or tree stands using high-powered rifles with telescopic sights, a practice known as food-plot hunting. The change has led to a rise in smaller hunting clubs that divide the land into areas where hunters are expected to stay while they hunt. This development has created conflict between the stationary food-plot hunters and the remaining drive hunters. The Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources has outlawed hunting deer with dogs in some areas as a result of the conflict. Whereas hunters once pursued a variety of game, food-plot hunting has created a deer-hunting monoculture. Hunters typically plant food plots for deer in September instead of going dove hunting. In mid-October, they begin hunting deer with bow and arrow when the state’s archery deer season opens, rather than hunt squirrels. A week-long muzzle-loader season in mid-November precedes the season for modern firearms that lasts until the last week of January, when many hunters used to shoot ducks. Few hunters now aim for quail and rabbit in February, choosing to take a break until turkey season begins in mid March.

In 2006, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimated direct expenditures on hunting reached $654 million in Alabama. Nature-based tourism, hunting, fishing, hiking, bird watching, camping, and boating had a $4.4 billion economic impact on Alabama that year. In 2007, Alabama residents bought more than 185,000 hunting licenses, not including children under the age of 16 and people who have bought lifetime hunting licenses. Since 1982, the state has sold more than 38,000 lifetime hunting licenses.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, interest in deer and turkey hunting remains high and continues to drive up the cost of recreational land prices. Commercial hunting operations have sprouted to create a new industry around these sports. But other forms of hunting are in decline as is the number of people participating in the sport. The people who make up the state’s increasingly urban population are moving farther from rural traditions, of which hunting was such an important part.

The Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources oversees more than 30 Wildlife Management Areas that are open to public hunting. The Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Division has also set aside some of its Forever Wild lands for hunting. In addition, the Alabama Wildlife Federation, the Alabama Chapter of Ducks Unlimited, and the Alabama Chapter of the National Wild Turkey Federation support the sport by raising money for habitat conservation. Each of the national forests in Alabama hosts a shooting range.

Further Reading

- Cook, Chris and Bill Gray. Biology and Management of White-tailed Deer in Alabama. Montgomery: Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, 2003.

- Henderson, Bob. The Fire Tower: Alabama Turkey Hunting. Bloomington, Ind.: 1st Books Press, 2003.

- Kelly, Tom. The Tenth Legion. Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press, 1973.