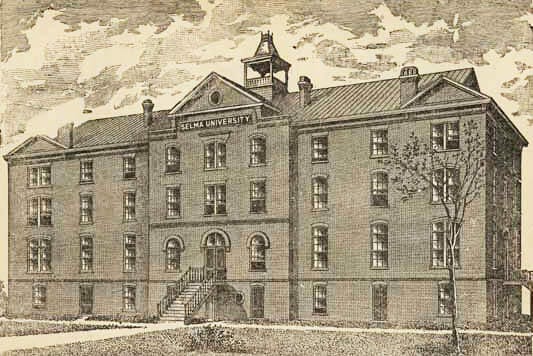

Selma University

Selma University, an historically black college (HBCU), opened its doors on January 1, 1878, with the goal of instructing black Baptist ministers and freedmen. The school has expanded over the years, from its initial enrollment of four students to graduating more than 4,000 students. The school enrolls approximately 540 students and since its founding has been the major project of the Alabama Missionary Baptist State Convention.

Selma University

Shortly after emancipation, in 1868, black Baptists in Alabama formed the Alabama Colored Baptist State Convention (ACBSC) for the purpose of providing gospel order, development, correct doctrine, and education for its pastors and the newly emancipated slaves. Leaders and members of the convention were convinced that one of the keys to improving their churches and elevating themselves socially and economically was through education. In 1873, William McAlpine, a former student at Talladega College who had raised funds for that institution, proposed at the annual ACBSC meeting in Tuscaloosa that the convention build a theological school in Alabama to educate young men. The convention sought the advice of white Baptists who also were meeting in Tuscaloosa, but they insisted that the effort was impractical and suggested that blacks attend a new school opening in Atlanta. Despite this negative advice, the black Baptists of Alabama, with the urging of McAlpine, began to establish their own school.

Selma University

Shortly after emancipation, in 1868, black Baptists in Alabama formed the Alabama Colored Baptist State Convention (ACBSC) for the purpose of providing gospel order, development, correct doctrine, and education for its pastors and the newly emancipated slaves. Leaders and members of the convention were convinced that one of the keys to improving their churches and elevating themselves socially and economically was through education. In 1873, William McAlpine, a former student at Talladega College who had raised funds for that institution, proposed at the annual ACBSC meeting in Tuscaloosa that the convention build a theological school in Alabama to educate young men. The convention sought the advice of white Baptists who also were meeting in Tuscaloosa, but they insisted that the effort was impractical and suggested that blacks attend a new school opening in Atlanta. Despite this negative advice, the black Baptists of Alabama, with the urging of McAlpine, began to establish their own school.

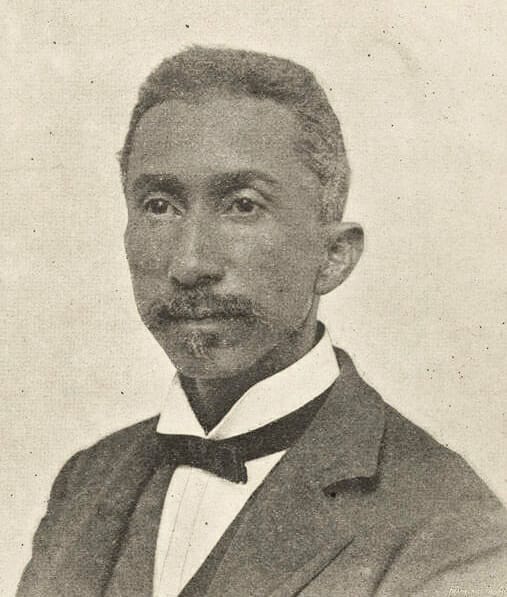

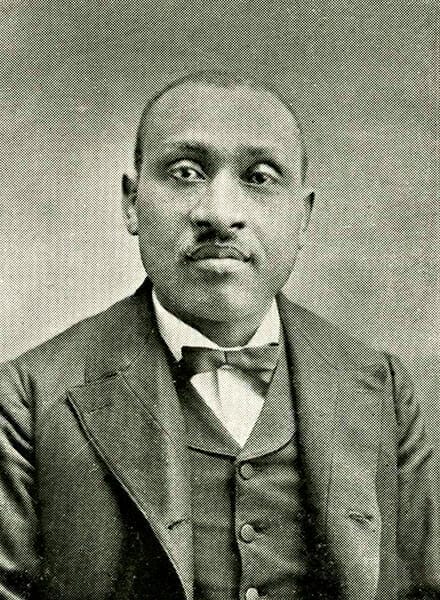

Charles Octavius Boothe

The state convention began planning for the school in 1874, and ACBSC delegates chose McAlpine to serve for six months as missionary and financial agent to raise money. Under the leadership of president Mansfield Tyler, the convention then met and elected a board of trustees. The following year, McAlpine and convention member Charles O. Boothe were selected to find a suitable building site, and in 1876, McAlpine raised $1,000 for the proposed school. In 1877, the convention chose Selma over Marion and Montgomery as the location for the Alabama Baptist Normal and Theological School, as the institution was first known. Its primary purpose was to train both lay teachers and Baptist ministers, and the trustees recommended Harrison Woodsmall, a white missionary from Indiana, to be the first president.

Charles Octavius Boothe

The state convention began planning for the school in 1874, and ACBSC delegates chose McAlpine to serve for six months as missionary and financial agent to raise money. Under the leadership of president Mansfield Tyler, the convention then met and elected a board of trustees. The following year, McAlpine and convention member Charles O. Boothe were selected to find a suitable building site, and in 1876, McAlpine raised $1,000 for the proposed school. In 1877, the convention chose Selma over Marion and Montgomery as the location for the Alabama Baptist Normal and Theological School, as the institution was first known. Its primary purpose was to train both lay teachers and Baptist ministers, and the trustees recommended Harrison Woodsmall, a white missionary from Indiana, to be the first president.

On January 1, 1878, the school opened with four students in the St. Phillips Street Baptist Church. In the same year, the trustees purchased the “Old Fair Grounds” in Selma for $3,000. The tract consisted of 36 acres of land, a large amphitheater, and several other buildings. The structures were renovated for $700 and used for classrooms and dormitories. Although the institution had as its primary purpose the training of ministers and teachers, instructors made some effort to provide general education for the newly freed slaves, especially in the Black Belt region, with an elementary and high school program.

Selma University

On March 1, 1881, it was incorporated as the Alabama Normal and Theological School. In 1885, the name was changed to Selma University, and in 1895 it became Alabama Baptist Colored University. During those early years, Pres. Edward M. Brawley oversaw the establishment of a collegiate department for the college and the name changed to Selma University. Prior to that time, the school had offered programs at the pre-college level. He also established the Alabama Baptist Women’s State Convention as a fund-raising auxiliary for Selma University. In 1900, Selma University had 382 students, with the vast majority in the normal-school program that trained teachers for black schools and 57 others in ministerial studies. By that time, Selma University had graduated a total of 142 individuals from its normal school and 15 from its college department with bachelor’s degrees since its inception. A limited number of ministerial students received a bachelor’s degree in Biblical Studies but most received certificates.

Selma University

On March 1, 1881, it was incorporated as the Alabama Normal and Theological School. In 1885, the name was changed to Selma University, and in 1895 it became Alabama Baptist Colored University. During those early years, Pres. Edward M. Brawley oversaw the establishment of a collegiate department for the college and the name changed to Selma University. Prior to that time, the school had offered programs at the pre-college level. He also established the Alabama Baptist Women’s State Convention as a fund-raising auxiliary for Selma University. In 1900, Selma University had 382 students, with the vast majority in the normal-school program that trained teachers for black schools and 57 others in ministerial studies. By that time, Selma University had graduated a total of 142 individuals from its normal school and 15 from its college department with bachelor’s degrees since its inception. A limited number of ministerial students received a bachelor’s degree in Biblical Studies but most received certificates.

Robert T. Pollard

In 1901, Baptist minister and education reformer Charles O. Boothe, a native of Mobile County, took over as president. He was succeeded by Robert T. Pollard, who served two terms, from 1902 to 1914 and from 1916 to 1930. During his presidency, Foster Hall and Dinkins Hall were added to the campus. In addition, Pollard erected a president’s home, a teacher’s cottage, and a teacher-training center. The school also purchased several lots for future expansion next to the main campus. During Pollard’s tenure, enrollment increased from 400 to 700 students in part owing to an expansion of course offerings. In 1921, the institution expanded its course offerings to include programs in industrial arts, such as domestic science, sewing, and business. Much of the increase came in the high school and college departments. Even though the number of county training schools had been growing in Alabama, these institutions emphasized industrial education. By contrast, Selma University was one of the few schools in the Black Belt where blacks could enroll in liberal-arts high school and college programs. The debt on the institution was also liquidated during Pollard’s tenure.

Robert T. Pollard

In 1901, Baptist minister and education reformer Charles O. Boothe, a native of Mobile County, took over as president. He was succeeded by Robert T. Pollard, who served two terms, from 1902 to 1914 and from 1916 to 1930. During his presidency, Foster Hall and Dinkins Hall were added to the campus. In addition, Pollard erected a president’s home, a teacher’s cottage, and a teacher-training center. The school also purchased several lots for future expansion next to the main campus. During Pollard’s tenure, enrollment increased from 400 to 700 students in part owing to an expansion of course offerings. In 1921, the institution expanded its course offerings to include programs in industrial arts, such as domestic science, sewing, and business. Much of the increase came in the high school and college departments. Even though the number of county training schools had been growing in Alabama, these institutions emphasized industrial education. By contrast, Selma University was one of the few schools in the Black Belt where blacks could enroll in liberal-arts high school and college programs. The debt on the institution was also liquidated during Pollard’s tenure.

Selma University found that its college program was not competitive with other black Baptist schools in terms of numbers or quality of instruction because it emphasized elementary school through senior college education. Other historically black denominational schools had closed their pre-college programs in order to concentrate on a college curriculum, and the board of trustees and convention leadership agreed upon a similar course of action for Selma University. Thus, they reorganized the school as a junior college with a separate school of religion in 1954.

Despite its failure to achieve accreditation from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), Selma University continued to attract students during the 1950s and 1960s. By 1968, the institution was participating in several federal programs that assisted veterans and economically disadvantaged students. Federal assistance through grants and scholarships helped increase enrollment to 310 by 1968, and the addition of dormitories in 1970 contributed to further increases. But student unrest over awards from federal programs and conflicts with administrators created tension among students and resulted in fires on the campus. The college also faced increasing debt that led to divisions among trustees in the 1970s, and enrollment plummeted to fewer than 100 students.

In 1982, Wilson Fallin Jr. became president of Selma University. The former president of Birmingham Baptist Bible College, Fallin had raised the academic standards of that institution. Fallin’s major contributions as head of Selma University were increasing the enrollment to 450, bringing in greater funding, and moving the school toward accreditation with SACS. Fallin’s success was largely the result of aggressive fundraising from alumni, churches, and businesses. Greater communication with pastors helped increase enrollment as well. In 1985, Fallin was succeeded by B. W. Dawson, who achieved full accreditation for the school in 1986. Unfortunately, accreditation was lost in 1994 after Dawson resigned from the institution because of conflict with trustees over his role as president.

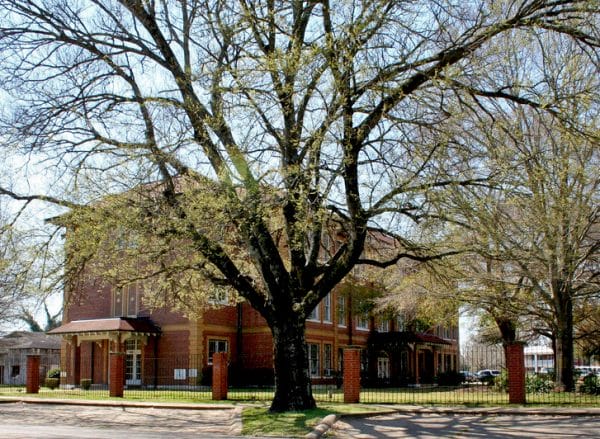

Selma University

Today, Selma University is primarily a Bible college with six satellite campuses in Mobile, Montgomery, Greenville, Eufaula, and Evergreen. It has liquidated much of its mortgage debt and applied for membership in the American Association of Biblical Higher Education. It remains the “pride of Alabama Baptists,” according to the Alabama Missionary Baptist State Convention, and has as its primary mission training persons for Christian ministry. Through the years, the institution has emphasized the training of ministers and teachers, but many graduates have gone on to become doctors, dentists, lawyers, and school administrators. Two of its most distinguished graduates are David and Theodore Jemison, both of whom served as president of the National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc. In 2023, the university received a $750,000 grant from the National Park Service to preserve Pollard Hall.

Selma University

Today, Selma University is primarily a Bible college with six satellite campuses in Mobile, Montgomery, Greenville, Eufaula, and Evergreen. It has liquidated much of its mortgage debt and applied for membership in the American Association of Biblical Higher Education. It remains the “pride of Alabama Baptists,” according to the Alabama Missionary Baptist State Convention, and has as its primary mission training persons for Christian ministry. Through the years, the institution has emphasized the training of ministers and teachers, but many graduates have gone on to become doctors, dentists, lawyers, and school administrators. Two of its most distinguished graduates are David and Theodore Jemison, both of whom served as president of the National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc. In 2023, the university received a $750,000 grant from the National Park Service to preserve Pollard Hall.

Further Reading

- Boothe, Charles Octavius. The Cyclopedia of the Colored Baptists of Alabama: Their Leaders and Their Work. Birmingham: Alabama Publishing Company, 1895.

- Catalogs of Selma University, 1900-2006. Selma University Library, Selma, Alabama.

- Fallin, Wilson, Jr. Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

- Fitts, Leroy. History of Black Baptists. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1985.

- Minutes of the Alabama Missionary Baptist State Convention. Archives of the Alabama Baptist Historical Society, Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.