Alabama AFL-CIO

Alabama AFL-CIO

Founded in 1956, the Alabama AFL-CIO promotes the political interests of local union branches that belong to larger national and international unions affiliated with the AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations). The Alabama affiliates were the first of any state to merge following the national merger in 1955. Located in Montgomery, Montgomery County, the organization lobbies state government on their behalf, assists union members and local unions who have problems with state agencies, endorses candidates for statewide office, mobilizes workers and communities, and educates voters.

Alabama AFL-CIO

Founded in 1956, the Alabama AFL-CIO promotes the political interests of local union branches that belong to larger national and international unions affiliated with the AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations). The Alabama affiliates were the first of any state to merge following the national merger in 1955. Located in Montgomery, Montgomery County, the organization lobbies state government on their behalf, assists union members and local unions who have problems with state agencies, endorses candidates for statewide office, mobilizes workers and communities, and educates voters.

Since its inception, legislative and electoral success has often eluded the Alabama AFL-CIO. Historically, only a small proportion of the workforce in Alabama has chosen to unionize, and not all of the local unions that exist statewide have joined and supported the Alabama labor council. Compounding the problem, even local unions associated with the Alabama AFL-CIO have not always cooperated or followed its direction.

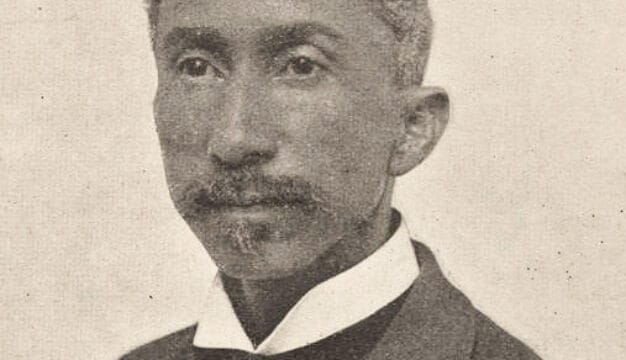

Barney Weeks

The challenges confronting the Alabama AFL-CIO transcend the state’s low union membership, the failure of many statewide local unions to join, and its inability to require even affiliated unions to follow its leadership. It has also contended with an often-hostile political environment. The Alabama AFL-CIO’s liberal political program is at odds with the state’s pervasive anti-union sentiment and generally conservative political values. This has been true regardless of which party rules the state house. In the 1950s and 1960s, anti-labor conservatives who controlled state government through the Alabama Democratic Party stymied the Alabama AFL-CIO’s political program. The same forces that dominate state politics still thwart labor’s liberal agenda but do so now through the Republican Party.

Barney Weeks

The challenges confronting the Alabama AFL-CIO transcend the state’s low union membership, the failure of many statewide local unions to join, and its inability to require even affiliated unions to follow its leadership. It has also contended with an often-hostile political environment. The Alabama AFL-CIO’s liberal political program is at odds with the state’s pervasive anti-union sentiment and generally conservative political values. This has been true regardless of which party rules the state house. In the 1950s and 1960s, anti-labor conservatives who controlled state government through the Alabama Democratic Party stymied the Alabama AFL-CIO’s political program. The same forces that dominate state politics still thwart labor’s liberal agenda but do so now through the Republican Party.

In 1956, the Alabama AFL-CIO was founded as the Alabama Labor Council, AFL-CIO. In 1962, its name changed to its current title. The Alabama AFL-CIO resulted from the merger of the Alabama State Federation of Labor (ASFL), which represented about 50,000 members statewide, and the Alabama State Industrial Union Council, which was affiliated with the rival CIO, and also claimed about 50,000 workers. The Alabama federation was significant because it marked the first marriage of AFL and CIO organizations in any state following the national merger of the AFL and CIO in 1955. Delegates to the 1956 Alabama AFL-CIO unity convention in Mobile, Mobile County, elected Carl Griffin, from the Painters Union and former president of the ASFL, as their first president. Griffin resigned within a year. In 1957, Barney Weeks, a typesetter and president of an International Typographical Union local in Montgomery, replaced Griffin and served as president for 26 years, until his retirement in 1983.

The state council grew under Weeks’s tenure but only after suffering severe political and financial losses as a result of its support for the emerging civil rights movement in the 1960s. Weeks believed that to be politically effective, the unions needed to ally with Black civil rights activists who shared the members’ political interests, including better public services and more progressive taxes, and shared the same political enemies: segregationist anti-labor legislators from Alabama’s Black Belt. Many unions in Alabama, especially steelworker locals around Birmingham, Jefferson County, opposed civil rights for Blacks and felt betrayed by the national Democratic Party, which supported such policies. Rank-and-file workers sympathized more with Gov. George Wallace‘s defense of segregation and his defiance of the national Democratic Party than with the state council’s policies and its loyalty to the Democrats.

Center for Labor Education and Research

Although the Alabama AFL-CIO stood by its principles under Weeks’s leadership, its courage and conviction came at a steep price. Local unions renounced their affiliation in protest of the state council’s support for Black civil rights. Membership dwindled from a peak of 107,000 in 1958 to half that number by 1965, and as local unions left, they took their dues money with them. Labor’s influence within the state government withered. The Wallace administration no longer solicited the Alabama AFL-CIO’s advice on appointments or invited its leaders to participate in negotiations on labor policy. Its political credibility suffered as well, and local unions in Alabama openly repudiated its endorsements. In the 1966 state elections, every candidate endorsed by the Alabama AFL-CIO lost.

Center for Labor Education and Research

Although the Alabama AFL-CIO stood by its principles under Weeks’s leadership, its courage and conviction came at a steep price. Local unions renounced their affiliation in protest of the state council’s support for Black civil rights. Membership dwindled from a peak of 107,000 in 1958 to half that number by 1965, and as local unions left, they took their dues money with them. Labor’s influence within the state government withered. The Wallace administration no longer solicited the Alabama AFL-CIO’s advice on appointments or invited its leaders to participate in negotiations on labor policy. Its political credibility suffered as well, and local unions in Alabama openly repudiated its endorsements. In the 1966 state elections, every candidate endorsed by the Alabama AFL-CIO lost.

By the 1970s, with the struggle over civil rights receding, membership in the Alabama AFL-CIO started to rise. The biracial coalition of Blacks and blue-collar whites within the Democratic Party that Weeks had envisioned began to yield higher membership numbers. Ironically enough, the new coalition developed under the auspices of a repentant and chastened George Wallace, whom the state council endorsed in his successful 1974 gubernatorial campaign. Just as Wallace apologized to Blacks for his previous racial politics, he also made amends with the Alabama AFL-CIO and invited it to participate with his administration. In 1974, for example, the Alabama AFL-CIO worked closely with Wallace officials to create a workers’ education program, the Center for Labor Education and Research (CLEAR), a workers’ education program at Jefferson State Community College in Birmingham.

Even as its political vision began to materialize, larger political and economic forces conspired against the Alabama AFL-CIO. Whereas 20 percent of all nonagricultural workers in Alabama had been unionized in 1964, the proportion of the organized workforce had slipped to 8 percent by 2000, with only 130,000 union members statewide. The decrease was particularly severe within the industrial wing of the Alabama labor movement, especially in the Birmingham steel mills and Gadsden, Etowah County, rubber plants, along the Mobile docks, and in textile mills and apparel firms throughout the state. Some plants closed when jobs moved overseas, and others downsized and replaced workers with labor-saving technology. The growth of service-sector jobs and the influx of immigrant and transplant workers and anti-union corporations, such as Mercedes-Benz, Honda, and Amazon, the second-largest employer in America, has also hampered organizing labor. The proportion of the workforce statewide that belonged to unions fell even further by 2021 to just 5.9 percent, with 115,000 union members within Alabama. Although the state AFL-CIO ranked 34th of the 50 states in union density, it could still take solace in the fact that it ranked higher than any other southern state.

U.S. Steel Fairfield Works

Along with the shrinking percentage of the Alabama workforce organized into unions, the state council continued to be frustrated by locals that refused to affiliate with it. By 2000, only 60 percent of AFL-CIO local unions in Alabama, representing about 60,000 workers, were dues-paying members of the state labor council. Twenty years later, membership had fallen to approximately 50,000 representing only 44 percent of all union members statewide. The steelworkers’ union, once the largest union represented within the Alabama AFL-CIO, experienced sharp declines as the last remaining steel plants outside Birmingham shut down. In Bessemer, Jefferson County, to the southwest of Birmingham, the former steel town has successfully transitioned from heavy industry to a distribution hub. The new Amazon warehouse in that community and the Alabama AFL-CIO’s fight to unionize workers there became an important flashpoint for the national labor movement in 2021 and into 2022 as the union has alleged that the company interfered in workers’ 2021 vote. Coal miners, government employees, teachers, and especially electrical workers now comprise a larger percentage of the state council membership.

U.S. Steel Fairfield Works

Along with the shrinking percentage of the Alabama workforce organized into unions, the state council continued to be frustrated by locals that refused to affiliate with it. By 2000, only 60 percent of AFL-CIO local unions in Alabama, representing about 60,000 workers, were dues-paying members of the state labor council. Twenty years later, membership had fallen to approximately 50,000 representing only 44 percent of all union members statewide. The steelworkers’ union, once the largest union represented within the Alabama AFL-CIO, experienced sharp declines as the last remaining steel plants outside Birmingham shut down. In Bessemer, Jefferson County, to the southwest of Birmingham, the former steel town has successfully transitioned from heavy industry to a distribution hub. The new Amazon warehouse in that community and the Alabama AFL-CIO’s fight to unionize workers there became an important flashpoint for the national labor movement in 2021 and into 2022 as the union has alleged that the company interfered in workers’ 2021 vote. Coal miners, government employees, teachers, and especially electrical workers now comprise a larger percentage of the state council membership.

The economy as well as the political environment in Alabama have witnessed remarkable changes. Too weak to claim credit by itself, the Alabama AFL-CIO contributed to party realignment in Alabama following the civil rights era. A competitive two-party system finally emerged in which differences between the Democratic and Republican parties became meaningful. The Democratic Party embraced Black voters and became a multiracial coalition that adopted much of labor’s liberal program of union security, public services, and progressive tax policy. The resurgent Republican Party, on the other hand, inherited much of the base among whites and conservatives from the old Democratic Party. Ironically, the success of the Alabama AFL-CIO’s political strategy to realign state politics and encourage two-party competition did not bring the political dividends that labor anticipated. Realignment did not dethrone anti-labor conservatives in Alabama but simply shifted their base from the Democratic Party to the Republican Party.

The Alabama AFL-CIO’s administrative structure has seen changes as well. The executive board still sets policy for the Alabama AFL-CIO. Two elected full-time officers—the president and secretary-treasurer—and 34 other elected board members from affiliated unions in Alabama comprise the board. Among them, the board recognizes five members each as representatives of the northern and southern districts of Alabama. Although the executive board has grown from 18 to 34 members, the main office staff has shrunk from three to two. The organization continues to hold biennial conventions to adopt policy and elect board members, who serve for four-year terms. The Alabama AFL-CIO also charters nine central labor councils, located throughout the state, that help carry out its work at the local level, and it is a member of AFL-CIO Region 5, which covers the Southeast. In recent decades, two presidents, in particular, have provided steady leadership for the union: D. Stewart “Buck” Burkhalter, from a paper workers’ local, and the current president, Bren Riley, from the steel workers.

Politically, the Alabama AFL-CIO still aligns with the Democratic Party, which is not competitive in elections. With Republicans firmly in control in Alabama, as they are throughout much of the South, it would take another political realignment for the Alabama AFL-CIO to be influential in state politics. The future success of the Alabama AFL-CIO depends upon reviving union membership and the ascendancy of the Democratic Party in a very conservative state. The former shows more signs of retreat than revitalization, and the latter seems to be more a spectator than a competitive party. If and when the trajectory in unionization reverses and the political winds tack left, the Alabama AFL-CIO will surely play an important role. In the meantime, it will continue to advocate for working people and social and economic justice in Alabama.

Further Reading

- Draper, Alan. Conflict of Interests: Organized Labor and the Civil Rights Movement in the South. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1994.

- Kundahl Jr., George G. “Organized Labor in Alabama State Politics.” Ph.D. diss. University of Alabama, 1967.

- Norrell, Robert J. “Labor Trouble: George Wallace and Union Politics in Alabama,” in Robert H. Zieger, ed. Organized Labor in the Twentieth Century South. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991.

- Taft, Philip. Organizing Dixie: Alabama Workers in the Industrial Era. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1981.