World War I and Alabama

Wartime Alabama

Alabama’s involvement with the United States’ participation in World War I in many ways reflected the state’s pre-war culture, economy, society, gender and racial relations, and politics. Mobilization generated a frenzy of activity but engendered few permanent changes, other than acting as a catalyst for the Great Migration, as tradition yielded only slightly to modernism.

Wartime Alabama

Alabama’s involvement with the United States’ participation in World War I in many ways reflected the state’s pre-war culture, economy, society, gender and racial relations, and politics. Mobilization generated a frenzy of activity but engendered few permanent changes, other than acting as a catalyst for the Great Migration, as tradition yielded only slightly to modernism.

From its beginnings in August 1914, the European war created problems in Alabama. Trade disruptions beginning in 1915 and America’s rapidly expanding efforts to supply the Allies affected Alabama’s economy before and after the United States declared war in April 1917. Significantly, British industrial production shifted from making cloth to making war material, so Britain’s demand for southern cotton plummeted, depressing cotton prices and reducing traffic in the port of Mobile. There, city leaders tried to improve local dock facilities to attract deep-draught ships, which they hoped would make port in Mobile when trade resumed. Only a lack of capital and concerted political wrangling finally convinced the state to create the Alabama State Docks Commission, to oversee dock construction in Mobile.

Events in other parts of the United States had an impact on Alabama as well. As industry began to supply the Allies with war material, more than 150,000 whites and approximately 85,000 blacks left rural Alabama for jobs in the North and in manufacturing centers elsewhere in the South. Landowners protested the resulting labor shortage and even sought to have labor recruiters from northern industries arrested, but these efforts could not stem the tide of out-migration. Birmingham suffered from a different problem shortly after the U.S. entered the conflict. Railroad traffic became snarled from New England to the Midwest, and with railcars sitting idle there, Birmingham’s steel production slowed precipitously because of a lack of access to markets. Only after December did the jam clear.

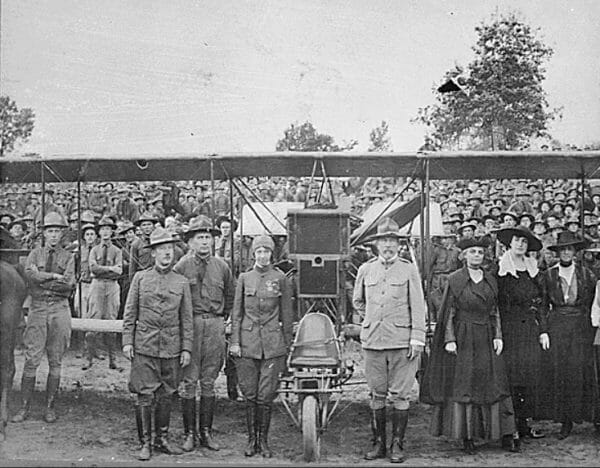

Aviator Ruth Law at Camp McClellan

Military mobilization engaged Alabama almost immediately after the United States declared war in April 1917. Powerful congressmen secured three training bases for the state. The Thirty-seventh Ohio “Buckeye” Division trained at Camp Sheridan, much to the delight of Montgomery’s merchants, who prospered from the new business, while Army pilots from Taylor Field enthralled Montgomery’s elite. Camp McClellan in Anniston hosted the Twenty-ninth “Blue-Gray” Division from the mid-Atlantic region.

Aviator Ruth Law at Camp McClellan

Military mobilization engaged Alabama almost immediately after the United States declared war in April 1917. Powerful congressmen secured three training bases for the state. The Thirty-seventh Ohio “Buckeye” Division trained at Camp Sheridan, much to the delight of Montgomery’s merchants, who prospered from the new business, while Army pilots from Taylor Field enthralled Montgomery’s elite. Camp McClellan in Anniston hosted the Twenty-ninth “Blue-Gray” Division from the mid-Atlantic region.

Alabama National Guard units, which had served in a military effort in Mexico against Francisco “Pancho” Villa’s rebellion from October 1916 to April 1917, returned just in time to be mobilized for the European war. Initially, Alabama units protected public utilities and infrastructure, but in August they were mustered into federal service. The First and Second Alabama Infantry entered the Army’s Thirty-first Infantry Division, whereas the Fourth Alabama became the 167th Infantry Regiment of the Forty-second (Rainbow) Division. The 167th fought in the 1918 Aisne-Marne Offensive, and the Thirty-first remained at Camp Wheeler in Georgia.

Ohio Boys at Camp Sheridan

In addition to providing 5,000 National Guardsmen and 7,000 other volunteers, Alabama contributed approximately 74,000 white and black draftees, called “selectmen,” to the Army. Most black troops were assigned to labor battalions, but two black units that trained in Alabama, Maryland’s First Separate Negro Company and Ohio’s Ninth Battalion of Infantry Colored, saw action with the Ninety-third Division under French command. More than 2,500 Alabamians were killed fighting in the fields of France.

Ohio Boys at Camp Sheridan

In addition to providing 5,000 National Guardsmen and 7,000 other volunteers, Alabama contributed approximately 74,000 white and black draftees, called “selectmen,” to the Army. Most black troops were assigned to labor battalions, but two black units that trained in Alabama, Maryland’s First Separate Negro Company and Ohio’s Ninth Battalion of Infantry Colored, saw action with the Ninety-third Division under French command. More than 2,500 Alabamians were killed fighting in the fields of France.

The state government prepared for war as well. Gov. Charles Henderson established the Alabama Council for Defense as the local arm of the Council of National Defense and appointed administrators to state subsidiaries of various nationwide resource administrations, such as the U.S. Food Administration and the War Industries Board. The Alabama Council for Defense took more than a year to find its footing, but after reorganizing in June 1918, it coordinated the war service of more than a dozen agencies.

Red Cross Headquarters in Montgomery, 1918

Alabamians from all walks of life pitched in to help the war effort. Many joined voluntary organizations such as the Red Cross, the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, the War Camp Community Service, the YMCA, the YWCA, and the Four-Minute Men and Women, which were groups of amateur orators who promoted the war effort. Others formed ad hoc service groups. Near Camps Sheridan and McClellan, women assisted soldiers’ families, provided transportation to and from camps, and hosted social gatherings to draw soldiers away from prostitutes and saloons. Local communities, professors from Alabama State Normal School for Negroes (now Alabama State University), and women’s clubs in Montgomery and Tuscaloosa organized canning factories to preserve Victory Garden produce and keep food affordable in their cities.

Red Cross Headquarters in Montgomery, 1918

Alabamians from all walks of life pitched in to help the war effort. Many joined voluntary organizations such as the Red Cross, the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, the War Camp Community Service, the YMCA, the YWCA, and the Four-Minute Men and Women, which were groups of amateur orators who promoted the war effort. Others formed ad hoc service groups. Near Camps Sheridan and McClellan, women assisted soldiers’ families, provided transportation to and from camps, and hosted social gatherings to draw soldiers away from prostitutes and saloons. Local communities, professors from Alabama State Normal School for Negroes (now Alabama State University), and women’s clubs in Montgomery and Tuscaloosa organized canning factories to preserve Victory Garden produce and keep food affordable in their cities.

The war had a direct economic impact on state industry. Federal money poured into the Muscle Shoals area and led to the construction of what became Wilson Dam and two nitrate plants along the Tennessee River, although they did not contribute to the war effort. Similarly, federal contracts drove the building of ship yards near Mobile. Millions of dollars in wages flowed into both areas, but the thousands of new workers encountered serious overcrowding. The war economy also improved demand for Birmingham’s iron products as well as the state’s timber, food, and fiber. Prices rose, and wages, job opportunities, and living standards improved.

Robert R. Moton

Despite white mistrust as war fever spread across the state, black Alabamians continually demonstrated their full support for the war. Black spokesmen like Robert R. Moton, G. T. Buford, Emmett Scott, and dozens of local leaders organized their segregated communities for patriotic rallies, Liberty Bond drives, draft registration, and send-offs for both black and white troop trains. Whenever possible, blacks ran parallel war services, including the Red Cross, ad hoc clubs, and even the men’s and women’s Four-Minute speakers’ series.

Robert R. Moton

Despite white mistrust as war fever spread across the state, black Alabamians continually demonstrated their full support for the war. Black spokesmen like Robert R. Moton, G. T. Buford, Emmett Scott, and dozens of local leaders organized their segregated communities for patriotic rallies, Liberty Bond drives, draft registration, and send-offs for both black and white troop trains. Whenever possible, blacks ran parallel war services, including the Red Cross, ad hoc clubs, and even the men’s and women’s Four-Minute speakers’ series.

On November 11, 1918, the Allies and Germany signed an armistice that effectively ended the war in which Americans had fought for only 19 months. World War I left a mixed legacy in Alabama. Though mobilization had demonstrated the efficiency of an expanded governmental role and had broken down some barriers to women and blacks participating in mainstream society, the war experience did not change Alabama’s traditional conservatism. For example, the Alabama legislature refused to consider the Nineteenth Amendment, so women in the state received the right to vote only after enough other states ratified it.

African Americans especially were disheartened by the lack of change after the war. Believing that wholehearted participation on the homefront and in the trenches would soften Jim Crow laws and practices, blacks quickly realized that their support had been in vain. Soldiers returned to segregation and inequality, and black leaders found their pleas for full citizenship ignored. In Alabama’s race relations, only the memory of the hope for full rights remained.

Montgomery Victory Parade 1919

World War I did advance a more Progressive agenda in state politics, however, because it exposed the generally poor health and low literacy rates among recruits from Alabama. Governor Henderson hired physician Hastings Hart of the Russell Sage Foundation to study the state’s institutions. Hart’s findings, including low spending on education and low school attendance compared with national averages, embarrassed Alabama politicians and enhanced the Progressive candidacy of Thomas Kilby, who served as governor from 1919 to 1923. Although unable to enact all the reforms he sought, particularly the elimination of the notorious convict-lease system, Kilby did use government power to make life in the state more equitable and to reform many outmoded institutions.

Montgomery Victory Parade 1919

World War I did advance a more Progressive agenda in state politics, however, because it exposed the generally poor health and low literacy rates among recruits from Alabama. Governor Henderson hired physician Hastings Hart of the Russell Sage Foundation to study the state’s institutions. Hart’s findings, including low spending on education and low school attendance compared with national averages, embarrassed Alabama politicians and enhanced the Progressive candidacy of Thomas Kilby, who served as governor from 1919 to 1923. Although unable to enact all the reforms he sought, particularly the elimination of the notorious convict-lease system, Kilby did use government power to make life in the state more equitable and to reform many outmoded institutions.

Overall, Alabamians fully participated in mobilizing and fighting America’s first “total war” of the twentieth century. After the armistice, they rapidly returned to life as they had known it, with a few changes in the political role of women and the social role of government. In the 1920 presidential election, candidate Warren Harding suggested the United States return to “normalcy.” By then, Alabama already had.

Further Reading

- Amerine, William H. Alabama’s Own in France. New York: Eaton & Gettinger, 1919.

- Frazer, Nimrod T. Send the Alabamians!: World War I Fighters in the Rainbow Division. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2014.

- Olliff, Martin T., ed. The Great War in the Heart of Dixie: Alabama in World War I. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

- Scribner, Christopher MacGregor. “Progress Versus Tradition in Mobile, 1900-1920.” In Mobile: The New History of Alabama’s First City, edited by Michael V. R. Thomason, 156-180. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.

- Truss, Ruth Smith. “The Alabama National Guard from 1900 to 1920.” Ph.D diss., University of Alabama, 1992.

- ———. “The Alabama National Guard’s 167th Infantry Regiment in World War I.” Alabama Review 56 (January 2003): 3-34.