Reuben Chapman (1847-49)

Reuben Chapman (1799-1882) was the 13th governor of Alabama, serving from 1847 to 1849. A state legislator and U.S. congressman, Chapman was propelled into the governor’s office by severe and lingering financial crises that centered on the State Bank of Alabama.

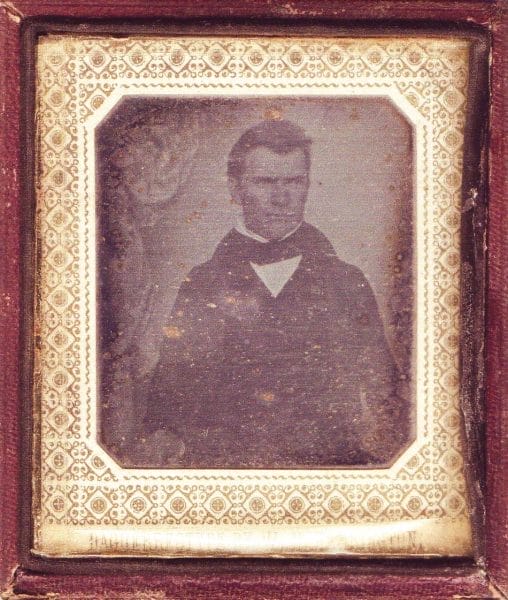

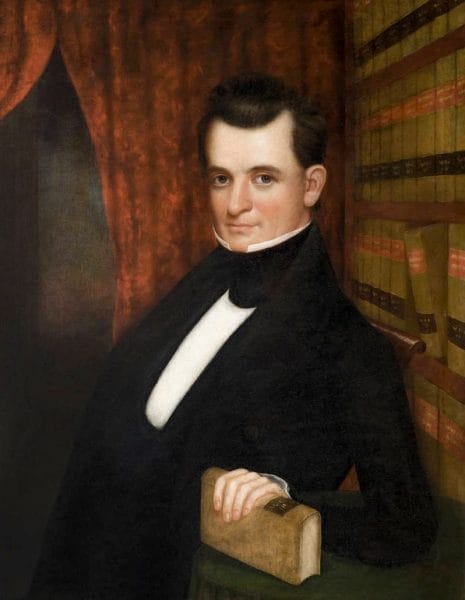

Reuben Chapman, 1847

Reuben Chapman was born in Virginia on July 15, 1799, the son of Ann Reynolds and Reuben Chapman, a minor officer in the Revolutionary War. He was educated in Bowling Green. In 1824, at age 25, he travelled on horse to Alabama to join his older brother Samuel, a Huntsville lawyer. Reuben read law in his brother’s office, then moved to Morgan County, and ultimately back to Huntsville, where he opened a law practice. In addition to his law practice, Chapman added to his income with cotton production. He built a large estate in Madison County and acquired a plantation in the Black Belt, thus gaining connections in both important areas of the state. At age 39, he married 16-year-old Felicia Pickett (a distant relation of George E. Pickett, of Pickett’s Charge), with whom he had six children. One nineteenth-century source described Chapman as “bright, humorous and impressive in conversation, with courtly manners.” Prospering through his use of enslaved labor, Chapman was an ardent states’ rights Democrat. Like many such men, Chapman’s chief recreation was politics. He became a state senator in 1832 and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives three years later. He remained in that office for 15 years as a solid, respectable party man with no particular claim to fame other than his dependability and conviviality.

Reuben Chapman, 1847

Reuben Chapman was born in Virginia on July 15, 1799, the son of Ann Reynolds and Reuben Chapman, a minor officer in the Revolutionary War. He was educated in Bowling Green. In 1824, at age 25, he travelled on horse to Alabama to join his older brother Samuel, a Huntsville lawyer. Reuben read law in his brother’s office, then moved to Morgan County, and ultimately back to Huntsville, where he opened a law practice. In addition to his law practice, Chapman added to his income with cotton production. He built a large estate in Madison County and acquired a plantation in the Black Belt, thus gaining connections in both important areas of the state. At age 39, he married 16-year-old Felicia Pickett (a distant relation of George E. Pickett, of Pickett’s Charge), with whom he had six children. One nineteenth-century source described Chapman as “bright, humorous and impressive in conversation, with courtly manners.” Prospering through his use of enslaved labor, Chapman was an ardent states’ rights Democrat. Like many such men, Chapman’s chief recreation was politics. He became a state senator in 1832 and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives three years later. He remained in that office for 15 years as a solid, respectable party man with no particular claim to fame other than his dependability and conviviality.

By the mid-1840s, events back home began to unfold that would propel him to higher office. Alabama by this time had endured a decade of depression, funding shortages, and sectional animosities between the planter-dominated Black Belt and the independent farmers of the northern hill country. In an era when each state determined its own currency policy, all of these tensions became focused on the status of the state-chartered Bank of Alabama, which was failing, and the issue of debtor-relief, which many Black Belt planters direly needed. The most prominent Democratic gubernatorial candidates, Nathaniel Terry and incumbent Joshua Lanier Martin, neutralized each other on these issues, with the former being pro-bank and pro-relief and the latter exactly the opposite. At the state nominating convention in 1847, these factions stalemated, and Chapman was brought forward as the compromise candidate. He won the general election handily.

Joshua L. Martin

Chapman was no political innovator. Anti-bank and anti-relief, his only response to the state’s many economic problems was to sit back and allow events to play out. He did reduce the bank commission from three members to one: the extremely capable and hard-nosed Francis S. Lyons, who dismantled the Bank of Alabama and paid most of its debts before retiring in 1853. Beyond that, Chapman vetoed a bill that would have established the Mobile and Ohio Railroad on the simple grounds that buried in the act was language that would have made the parent company tax-exempt. A less offensive measure passed. Chapman was deeply interested in the affairs of the University of Alabama, especially an open chair in geology and agriculture. He wisely saw that the two were not the same and argued for a separate chair in agricultural studies complete with an experimental farm. He did not win his argument, but he did secure the appointment of a state geologist, a novel concept at the time. He proposed taxing land that had recently been purchased from the federal government, although previous law and tradition left such lands tax-free for five years. The proposition failed.

Joshua L. Martin

Chapman was no political innovator. Anti-bank and anti-relief, his only response to the state’s many economic problems was to sit back and allow events to play out. He did reduce the bank commission from three members to one: the extremely capable and hard-nosed Francis S. Lyons, who dismantled the Bank of Alabama and paid most of its debts before retiring in 1853. Beyond that, Chapman vetoed a bill that would have established the Mobile and Ohio Railroad on the simple grounds that buried in the act was language that would have made the parent company tax-exempt. A less offensive measure passed. Chapman was deeply interested in the affairs of the University of Alabama, especially an open chair in geology and agriculture. He wisely saw that the two were not the same and argued for a separate chair in agricultural studies complete with an experimental farm. He did not win his argument, but he did secure the appointment of a state geologist, a novel concept at the time. He proposed taxing land that had recently been purchased from the federal government, although previous law and tradition left such lands tax-free for five years. The proposition failed.

Chapman was firm in his opposition to banks, and therein lay part of his downfall. In his inaugural speech, Chapman had announced his firm opposition “to the policy of chartering banks of any description.” This intransigent stand was rapidly becoming a lonely one. With no settled policy on banking and currency, Alabamians had no stable money supply. As the price of cotton began to rise and influential men in both parties began to press their schemes for railroads to transport their crop, pressure for a rational banking system mounted. The impasse revived the career of Henry Collier, a Tuscaloosa lawyer, whose solution to the bank problem was to let them proliferate as privately chartered, state-sanctioned institutions. By 1849, Collier had won over most of the Democrats and a fair number of Whigs.

Henry Watkins Collier

To add to his problems, Chapman had blundered badly early in his term. Through death and a resignation, both of Alabama’s Senate seats fell open in 1848. Despite an unwritten rule that the seats be divided between the northern and southern sections of the state, Chapman appointed two south Alabamians to fill out the unexpired terms. This gaffe, added to the increasing appeal of private banking, blocked any real chance Chapman had for renomination. At the nominating convention, Collier won, and won again in the election. Chapman’s failure to win the convention in 1849 marked the first time that a Democratic incumbent had failed to be given a chance for a second term. (Martin, having run as an independent, was not technically a Democrat.) In quiet acceptance of the inevitable, Chapman’s last message to the legislature gave blessing to Collier’s bank plans, which the latter vigorously pursued.

Henry Watkins Collier

To add to his problems, Chapman had blundered badly early in his term. Through death and a resignation, both of Alabama’s Senate seats fell open in 1848. Despite an unwritten rule that the seats be divided between the northern and southern sections of the state, Chapman appointed two south Alabamians to fill out the unexpired terms. This gaffe, added to the increasing appeal of private banking, blocked any real chance Chapman had for renomination. At the nominating convention, Collier won, and won again in the election. Chapman’s failure to win the convention in 1849 marked the first time that a Democratic incumbent had failed to be given a chance for a second term. (Martin, having run as an independent, was not technically a Democrat.) In quiet acceptance of the inevitable, Chapman’s last message to the legislature gave blessing to Collier’s bank plans, which the latter vigorously pursued.

Even before his enforced retirement from state office, Chapman had become deeply involved in the controversy over slavery and its extension to the territories acquired after the Mexican War. The 1848 presidential election had been especially contentious, with northern Democrats joining antislavery Whigs in 1848 to form the Free Soil Party, whose platform endorsed the Wilmot Proviso, a rider to a wartime appropriations bill that would have barred slavery from any territories acquired from Mexico. The situation became even more complicated when gold was discovered in California, a territory primed for statehood. Chapman found his voice amidst this turmoil. He immediately expressed his opposition to any actions that might restrict the spread of slavery, and his public denunciations put him in line with a group of states’ rights extremist Democrats. The rising star of this group was Alabamian William Lowndes Yancey, and it was he who presided over the Democratic convention in 1847 and who nominated Chapman.

William Lowndes Yancey

Chapman lived up to Yancey’s hopes. He used his governorship as a platform to rail against any attempt to exclude slavery from California (although most southern politicians had already given up this idea). He was determined to prevent anyone from accusing Alabama Democrats of being slow to defend slavery and the right to take enslaved people into the territories. Prompted by Yancey, Chapman called for a southern convention to mount a unified attack on any anti-slavery legislation. He warned that if any such legislation passed, southerners would have to consider secession. The following year southern states met in a convention in Memphis, but by that point much of its secessionist agenda had been made irrelevant by the Compromise of 1850, a series of bills that balanced the admission of a free California with more aggressive protections for slavery where it already existed.

William Lowndes Yancey

Chapman lived up to Yancey’s hopes. He used his governorship as a platform to rail against any attempt to exclude slavery from California (although most southern politicians had already given up this idea). He was determined to prevent anyone from accusing Alabama Democrats of being slow to defend slavery and the right to take enslaved people into the territories. Prompted by Yancey, Chapman called for a southern convention to mount a unified attack on any anti-slavery legislation. He warned that if any such legislation passed, southerners would have to consider secession. The following year southern states met in a convention in Memphis, but by that point much of its secessionist agenda had been made irrelevant by the Compromise of 1850, a series of bills that balanced the admission of a free California with more aggressive protections for slavery where it already existed.

For the next decade, Chapman spent most of his energy tending to his plantations. In his only other run for office, he defeated Jeremiah Clemens, a Know-Nothing candidate and relative of Samuel Clemens (better known as Mark Twain) for a seat in the state legislature in 1855. Although Chapman largely retired from politics, the state’s Democrats began to adopt many of the Whigs’ banking and economic schemes, but the Whig Party itself collapsed, at least partly because it was unable in the South to match the Democrats’ intense rhetoric over slavery. By 1860, the pro-slavery zealotry of southern Democrats, especially from men like Yancey, had made it impossible for them to compromise. Too late, Chapman saw the probable destination of his party. When the Charleston convention of 1860 fell apart over the nomination of Stephen Douglas, Chapman travelled to a second convention at Baltimore to argue for reconciliation and compromise. He failed, then returned home to support the Confederacy. During the ensuing war, Chapman lost a son in battle, his home was burned, and he spent time imprisoned by federal troops. Like so many of his class, however, he came back and prospered, and his estate in Huntsville was considerable when he died on May 16, 1882. He was interred in Maple Hill Cemetery in Huntsville.

Further Reading

- Brantley, William H. Banking in Alabama, 1816-1860. 2 vols. Birmingham: Birmingham Printing Co., 1961.

- Inaugural Address of Governor Chapman, Delivered December 16, 1847. Montgomery: McCormick and Walsh, 1847.

- Thornton, J. Mills, III. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.