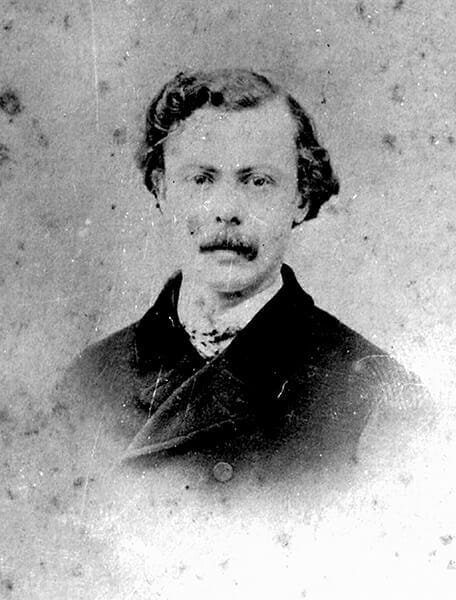

Henry Hotze

Henry Hotze

Although he lived in Alabama for less than a decade, Henry Hotze (1834-1887) left a significant and often infamous record of literary, military, and diplomatic service to his adopted state and to the Confederacy. From 1855 to 1865, Hotze was an associate editor for the Mobile Register, served in the Confederate Army and as a Confederate diplomat, and edited a London-based newspaper that promoted the Confederate cause. His writings promoting a scientific hierarchy of race-based intelligence were used by white supremacists as a justification for slavery. A sometimes overlooked figure from the American Civil War, Hotze was perhaps the South’s most effective propagandist abroad.

Henry Hotze

Although he lived in Alabama for less than a decade, Henry Hotze (1834-1887) left a significant and often infamous record of literary, military, and diplomatic service to his adopted state and to the Confederacy. From 1855 to 1865, Hotze was an associate editor for the Mobile Register, served in the Confederate Army and as a Confederate diplomat, and edited a London-based newspaper that promoted the Confederate cause. His writings promoting a scientific hierarchy of race-based intelligence were used by white supremacists as a justification for slavery. A sometimes overlooked figure from the American Civil War, Hotze was perhaps the South’s most effective propagandist abroad.

Henry Hotze was born in Zurich, Switzerland, on September 2, 1834, to Rudolph Hotze, a captain in the French Royal Service, and Sophie Esslinger. Little is known about his childhood other than that he received a very strong Jesuit education. Around 1850, Hotze emigrated to the United States and ended up in Mobile. On June 27, 1856, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen. Outgoing and well-educated, Hotze soon made contacts among Mobile’s elites. One of his mentors was Josiah C. Nott, physician, scientist, and author, who promoted the study of race-based intelligence. Nott enlisted Hotze to translate Count Arthur de Gobineau’s Essai sur L’inégalité des Races Humaines (Essay on the Inequality of Human Races), to which Hotze added his own introduction of more than 100 pages. Hotze’s version, entitled Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races (1856), was a detailed discussion of various cultures that purported to prove through science a hierarchy of racial intelligence among various groups of people based on skin color and continent of origin. Proponents of slavery used his finished product as a manifesto on the justification of slavery and subjugation. Hotze specifically adapted Gobineau’s racial views to justify the unequal treatment of what he believed to be unequal races.

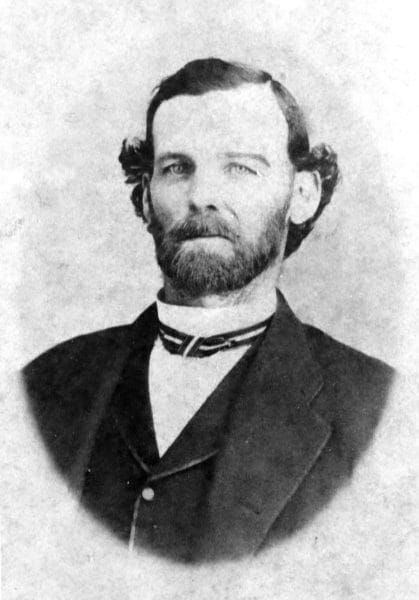

John Forsyth Jr.

In Mobile, Hotze served in several municipal positions, including secretary of the Mobile Board of Harbor Commissioners and as the secretary to the Belgian mission from 1858 to 1859. He then worked as an associate editor at John Forsyth’s Mobile Register. Hotze’s tenure at the Register coincided with campaign period leading up to the presidential election of 1860, and he worked with Forsyth to support the candidacy of Stephen A. Douglas. After the Civil War began, Hotze entered the more public phase of his career. As a member of the Mobile Cadets, a military organization made up mostly of Mobile’s affluent sons, Hotze was sent to Virginia as part of the Third Alabama Infantry Regiment. A journalist by profession, he wrote firsthand accounts of his brief time in the Confederate military, sending a series of letters back to the Mobile Register under the pseudonym “Cadet.” While on active duty, Hotze was never involved in any hostile action. One year later, Hotze, by then working for the Confederate State Department in London, published, in his own newspaper, a series of articles under the title “Three Months in the Confederate Army.” Both accounts are primarily filled with the routine aspects of camp life near Lynchburg and Norfolk, Virginia. Although Hotze describes the hard work involved in setting up the camp, his accounts of the first few weeks of his tour focus on descriptions of a very lively social scene.

John Forsyth Jr.

In Mobile, Hotze served in several municipal positions, including secretary of the Mobile Board of Harbor Commissioners and as the secretary to the Belgian mission from 1858 to 1859. He then worked as an associate editor at John Forsyth’s Mobile Register. Hotze’s tenure at the Register coincided with campaign period leading up to the presidential election of 1860, and he worked with Forsyth to support the candidacy of Stephen A. Douglas. After the Civil War began, Hotze entered the more public phase of his career. As a member of the Mobile Cadets, a military organization made up mostly of Mobile’s affluent sons, Hotze was sent to Virginia as part of the Third Alabama Infantry Regiment. A journalist by profession, he wrote firsthand accounts of his brief time in the Confederate military, sending a series of letters back to the Mobile Register under the pseudonym “Cadet.” While on active duty, Hotze was never involved in any hostile action. One year later, Hotze, by then working for the Confederate State Department in London, published, in his own newspaper, a series of articles under the title “Three Months in the Confederate Army.” Both accounts are primarily filled with the routine aspects of camp life near Lynchburg and Norfolk, Virginia. Although Hotze describes the hard work involved in setting up the camp, his accounts of the first few weeks of his tour focus on descriptions of a very lively social scene.

In the fall of 1861, the Confederate government sent Hotze on a special mission to Europe to purchase arms, but when he arrived in Great Britain, he came to believe that his time could be better spent on pro-Confederate diplomacy and propaganda. In November 1861, he successfully lobbied for an appointment as a “commercial agent” to London. Such an agent would normally be charged with procuring arms and supplies for the Confederate armies, but Hotze was actually sent to keep the Confederate government apprised of European public opinion and to present the Confederate cause in the best possible light to the local reading public. Working in an anonymous fashion, Hotze arranged for an unsigned editorial to be inserted in the London Morning Post. In March 1862, Hotze used this newfound access to contribute a series of four letters to the Post. Writing under the pseudonym “Moderator,” Hotze detailed the legality, necessity, practicality, and desirability of southern independence and Europe’s recognition of the Confederacy in a piece entitled “The Question of Recognition of the Confederate States.”

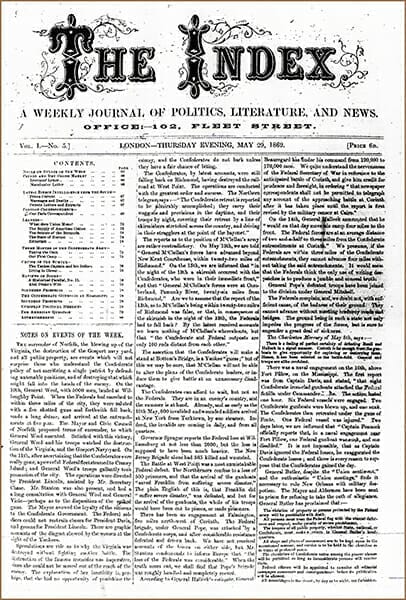

The Index

By the end of April, Hotze had made the most important decision of his foreign tenure. He informed the Confederate government that he wanted to publish a newspaper devoted to the Confederate cause and used his journalist skills to edit a European-based Confederate newspaper, The Index, which first appeared on May 1, 1862. For the next three years, the paper was an effective means of presenting propaganda to an often sympathetic, yet in Hotze’s opinion, sadly misinformed population. Although never exceeding a circulation of 2,250, the Index was read by many in the British government and by a sizeable number of Confederate sympathizers in Europe. The weekly Index published accounts of Civil War battles that were surprisingly accurate, given Hotze’s position as a propagandist, as well as editorials pushing for European recognition of the Confederacy and, as the South neared defeat, an increasing amount of venomous racist propaganda. Although slavery was illegal in Britain, Hotze’s racial diatribes struck a responsive chord among groups such as the Anthropological Society of London, a group that shared similar views. As the war ended, Hotze realized the Index could no longer stay afloat financially. He published the 172nd and final issue on August 12, 1865. Although it appeared four months after Lee’s surrender, Hotze remained pro-Confederate and defiant until the end.

The Index

By the end of April, Hotze had made the most important decision of his foreign tenure. He informed the Confederate government that he wanted to publish a newspaper devoted to the Confederate cause and used his journalist skills to edit a European-based Confederate newspaper, The Index, which first appeared on May 1, 1862. For the next three years, the paper was an effective means of presenting propaganda to an often sympathetic, yet in Hotze’s opinion, sadly misinformed population. Although never exceeding a circulation of 2,250, the Index was read by many in the British government and by a sizeable number of Confederate sympathizers in Europe. The weekly Index published accounts of Civil War battles that were surprisingly accurate, given Hotze’s position as a propagandist, as well as editorials pushing for European recognition of the Confederacy and, as the South neared defeat, an increasing amount of venomous racist propaganda. Although slavery was illegal in Britain, Hotze’s racial diatribes struck a responsive chord among groups such as the Anthropological Society of London, a group that shared similar views. As the war ended, Hotze realized the Index could no longer stay afloat financially. He published the 172nd and final issue on August 12, 1865. Although it appeared four months after Lee’s surrender, Hotze remained pro-Confederate and defiant until the end.

With the suspension of his newspaper, Hotze quickly faded from public view. Very little is known of his final 20 years. Although he apparently maintained his U.S. citizenship, Hotze never returned to the United States. He obviously kept writing in some form because his obituary made mention that in his later years, he “received various decorations from foreign governments for services as a publicist.” In 1868 he married Ruby Senac, a daughter of the Confederate paymaster in Europe. Hotze moved several times between London and Paris until, after a long period of illness, he died in Zug, Switzerland, on April 19, 1887.

Additional Resources

Bonner, Robert E. “Slavery, Confederate Diplomacy, and the Racialist Mission of Henry Hotze.” Civil War History 51 (September 2005): 288-316.

Burnett, Lonnie A. Henry Hotze, Confederate Propagandist. Selected Writings on Revolution, Recognition, and Race. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

Cullop, Charles C. Confederate Propaganda in Europe, 1861-1865. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1969

Dufour, Charles L. Nine Men in Gray. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

Oates, Stephen B. “Henry Hotze: Confederate Agent Abroad.” Historian 27 (February 1965): 131-54.