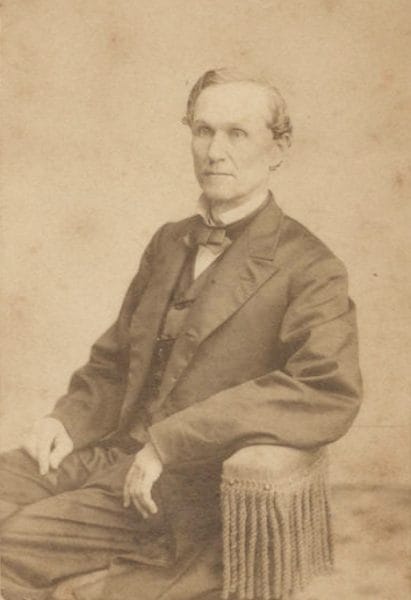

John Gill Shorter (1861-63)

John Gill Shorter

John Gill Shorter (1818–1872) won the gubernatorial election of 1861 just as Civil War hardships began to be felt by the people of Alabama. A Jacksonian Democrat, Shorter had entered state politics in 1845 when the sectional conflict over the expansion of slavery that would ultimately lead to war first erupted. Elected on a platform of limited government, the realities of war soon forced Shorter to expand government funding and programs and ultimately resulted in his electoral defeat. The town of Shorter, Macon County, is named for him.

John Gill Shorter

John Gill Shorter (1818–1872) won the gubernatorial election of 1861 just as Civil War hardships began to be felt by the people of Alabama. A Jacksonian Democrat, Shorter had entered state politics in 1845 when the sectional conflict over the expansion of slavery that would ultimately lead to war first erupted. Elected on a platform of limited government, the realities of war soon forced Shorter to expand government funding and programs and ultimately resulted in his electoral defeat. The town of Shorter, Macon County, is named for him.

John Gill Shorter was born in Monticello, Georgia, on April 3, 1818. In 1833, Shorter’s father moved to east Alabama, where he began acquiring property in and around Irwinton (later renamed Eufaula) in the future Barbour County. John Gill joined his family in 1837 after graduating from the University of Georgia. By the mid-1840s, the Shorters had acquired enough land to rank them among the wealthiest families in Barbour County. Shorter and his brother Eli also established one of the most successful law practices in their part of the state. Shorter married Mary Jane Battle, also of Eufaula, in 1843, and they had one daughter who lived to maturity.

The Shorter brothers, like many young men of their profession, used their local influence to build successful political careers. Being the son of a man devoted to the principles of Jacksonian Democracy, John Gill joined the Barbour County Democratic Party. In 1845, he won election to the state Senate and served one term. Shorter returned to public office in 1851, having won seat in the Alabama House of Representatives. He left the state house when governor Henry Collier appointed him circuit judge. He then won election to the judgeship in 1852. Shorter remained a judge until his election as governor in 1861.

William Lowndes Yancey

Though Shorter entered politics as a Jacksonian Democrat, he soon moved away from the Jacksonians. He, ardent states’ rights advocate William Lowndes Yancey, and other young Democratic politicians rebelled against older Democrats and built a Democratic faction devoted to a forceful defense of slavery and the promotion of southern economic development. Along with fellow delegates to the 1850 Nashville Convention, Shorter sought to make expansion of slavery into the territories acquired from Mexico the central issue of southern politics. Although he was not in favor of secession in the early 1850s, he and his allies did believe that the region should prepare for that possibility if other means of redressing southern grievances failed. Through the 1850s, Shorter devoted much energy to persuading his constituents that proposals to limit slavery were the first steps toward eventual abolition of the institution where it already existed.

William Lowndes Yancey

Though Shorter entered politics as a Jacksonian Democrat, he soon moved away from the Jacksonians. He, ardent states’ rights advocate William Lowndes Yancey, and other young Democratic politicians rebelled against older Democrats and built a Democratic faction devoted to a forceful defense of slavery and the promotion of southern economic development. Along with fellow delegates to the 1850 Nashville Convention, Shorter sought to make expansion of slavery into the territories acquired from Mexico the central issue of southern politics. Although he was not in favor of secession in the early 1850s, he and his allies did believe that the region should prepare for that possibility if other means of redressing southern grievances failed. Through the 1850s, Shorter devoted much energy to persuading his constituents that proposals to limit slavery were the first steps toward eventual abolition of the institution where it already existed.

Shorter’s political goals were not limited to defending slavery. Concerned about the economic future of the South, he joined other young Alabama Democrats in linking sectionalism to a vision of economic development quite different from their Jacksonian forbears. Unlike older Jacksonians, Shorter endorsed free trade, government investment in education, and internal improvements. This combination of education and economic development, Shorter believed, would expand economic opportunities for white citizens, while ending the South’s dependence on the North. Shorter thought that a more economically independent South would gain enough influence within the Union to fight off threats to slavery. If secession became inevitable, then economic development would prepare the South for separation and independent nationhood.

For Shorter, the election of Abraham Lincoln as president meant the end of southern compromise with opponents of slavery. He joined other supporters of secession in creating the Confederate States of America. Gov. Andrew B. Moore named Shorter a commissioner to Georgia and charged him with urging the Georgians to cooperate in secession. He next sought and won election to the Provisional Confederate Congress, where he worked on the Confederate constitution. Shorter was responsible for the compromise on admission of new states to the Confederacy that ended a bitter disagreement over the status of slavery in territories that might be added in the future.

Thomas Hill Watts

In August 1861, Shorter defeated Thomas Hill Watts of Montgomery and John E. Moore of Florence to become the first governor elected under the flag of the Confederate States of America. His inaugural address sought to unite Alabamians as a people distinct from the “Yankee race” and spoke of the need to end commercial, social, and political dependence on the North. Shorter expressed hope that the people would devote themselves to the sacrifice that would be required in the coming conflict.

Thomas Hill Watts

In August 1861, Shorter defeated Thomas Hill Watts of Montgomery and John E. Moore of Florence to become the first governor elected under the flag of the Confederate States of America. His inaugural address sought to unite Alabamians as a people distinct from the “Yankee race” and spoke of the need to end commercial, social, and political dependence on the North. Shorter expressed hope that the people would devote themselves to the sacrifice that would be required in the coming conflict.

The realities of the war soon forced Shorter to compromise virtually every principle he had publicly stood for in the 1850s. Although he had been a man who had defended states’ rights and limited government, he would now participate in the greatest expansion of central government power to that point in American history. Not long after his inauguration, in April 1862, the Confederate government enacted a law requiring men to serve in the Confederate Army, and Shorter, after some protests, assisted in its enforcement. To Alabamians, and most other Americans, no greater violation of individual liberty existed than forcing a man to serve in the army.

Shorter reluctantly expanded the power of state government. Faced with a critical shortage of manpower for the construction of defenses at Mobile, Shorter sought legislation to allow him to require slaveowners to provide enslaved workers to the state. Until the legislature passed a law in October 1862, the governor forced enslaved people into service under his emergency powers. For the remainder of his term, he faced severe criticism from slaveowners over this policy. Here again, Shorter abandoned principle when facing a difficult reality and would pay a political price.

Consistent with his prewar hostility toward government provision of welfare for the poor, Shorter opposed legislation to expand a state aid program for the families of soldiers to include all citizens in need. When the legislature began consideration of laws to control soaring prices so people could afford food, Shorter argued that such legislation would make matters worse. The governor did not stop passage of the bill, but the version that he signed was much weaker thanks to his opposition. By 1863, however, Shorter could no longer ignore the popular demand for government action to help all indigents. Thus he supported a measure passed in 1863 that appropriated funds to be distributed to counties for indigent citizens. He also employed state agents to purchase needed foodstuffs for distribution throughout the state.

Andrew Barry Moore

Complicating matters for Shorter and the government was a deteriorating military situation in north Alabama and a continuing threat to Mobile. Federal troops advanced into north Alabama, occupying much of that part of the state by the end of Shorter’s term. The governor appointed his predecessor Andrew B. Moore as his military aid and instructed him to raise troops to resist the advance of the U.S. forces, but shortages of men and weapons frustrated Moore’s efforts. Unable to keep federal forces out of north Alabama, Shorter hoped to prevent their occupation of Mobile. Throughout his term, U.S. naval forces maintained a presence outside of Mobile Bay, forcing state government to use limited resources to defend against a potential invasion from the south.

Andrew Barry Moore

Complicating matters for Shorter and the government was a deteriorating military situation in north Alabama and a continuing threat to Mobile. Federal troops advanced into north Alabama, occupying much of that part of the state by the end of Shorter’s term. The governor appointed his predecessor Andrew B. Moore as his military aid and instructed him to raise troops to resist the advance of the U.S. forces, but shortages of men and weapons frustrated Moore’s efforts. Unable to keep federal forces out of north Alabama, Shorter hoped to prevent their occupation of Mobile. Throughout his term, U.S. naval forces maintained a presence outside of Mobile Bay, forcing state government to use limited resources to defend against a potential invasion from the south.

As the gubernatorial election of 1863 approached, Shorter, who had always resisted the expansion of government power, now faced a political opposition critical of the greatest expansion of state government in Alabama history. Undoubtedly many in the state survived the war because of the limited support the state provided. But this did not move voters to cast their ballots for Shorter in 1863. Men who thought the government had done too much joined men who thought the government had done too little to elect former Whig Thomas Hill Watts. Shorter did not even win his home county, Barbour. For the remainder of the war, he assisted Governor Watts when asked. After the war, John Gill Shorter returned to Eufaula where he resumed the practice of law until his death on May 29, 1872.

Further Reading

- John Gill Shorter papers, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama.

- McMillan, Malcolm C. The Disintegration of a Confederate State: Three Governors and Alabama’s Wartime Home Front, 1861-1865. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1986.