Tallulah Bankhead

Tallulah Bankhead at 16

Tallulah Bankhead (1902-1968) was a talented actress and comedian, a popular public personality, and a determined champion of racial tolerance and equality. Although best remembered today for her performance in the film Lifeboat and as a madcap Jazz Age celebrity, her awards for film, live theater, and radio demonstrate that critics of her generation considered her a capable and talented performer in several performing arts media. She was born into an illustrious Alabama family that included grandfather John Hollis Bankhead, father William Bankhead, and uncle John Hollis Bankhead II, all U.S. Congressmen, and aunt Marie Bankhead Owen, who succeeded her husband Thomas Owen as Alabama’s state archivist.

Tallulah Bankhead at 16

Tallulah Bankhead (1902-1968) was a talented actress and comedian, a popular public personality, and a determined champion of racial tolerance and equality. Although best remembered today for her performance in the film Lifeboat and as a madcap Jazz Age celebrity, her awards for film, live theater, and radio demonstrate that critics of her generation considered her a capable and talented performer in several performing arts media. She was born into an illustrious Alabama family that included grandfather John Hollis Bankhead, father William Bankhead, and uncle John Hollis Bankhead II, all U.S. Congressmen, and aunt Marie Bankhead Owen, who succeeded her husband Thomas Owen as Alabama’s state archivist.

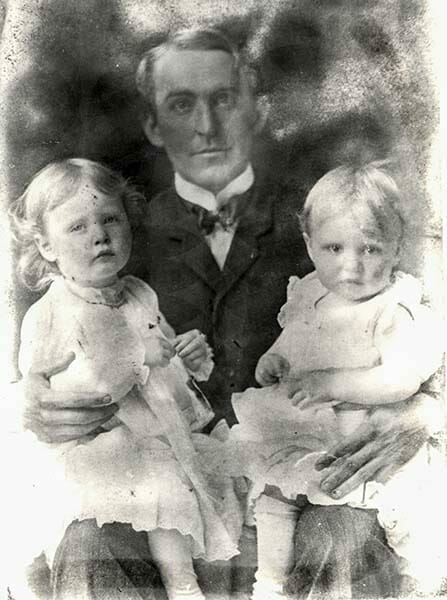

William B. Bankhead with Eugenia and Tallulah

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead was born on January 31, 1902, in Huntsville, the daughter of Adelaide Eugenia Sledge Bankhead and William Brockman Bankhead. Her paternal grandparents were then-U.S. Congressman John Hollis Bankhead and Tallulah James Brockman Bankhead, for whom she was named. (Tallulah’s grandmother had been named for Tallulah Falls, Georgia, which her parents had visited on their honeymoon.) Tallulah’s mother died on February 23 of complications from childbirth, and Tallulah was christened at the Episcopal Church of the Nativity in Huntsville after her mother’s funeral there.

William B. Bankhead with Eugenia and Tallulah

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead was born on January 31, 1902, in Huntsville, the daughter of Adelaide Eugenia Sledge Bankhead and William Brockman Bankhead. Her paternal grandparents were then-U.S. Congressman John Hollis Bankhead and Tallulah James Brockman Bankhead, for whom she was named. (Tallulah’s grandmother had been named for Tallulah Falls, Georgia, which her parents had visited on their honeymoon.) Tallulah’s mother died on February 23 of complications from childbirth, and Tallulah was christened at the Episcopal Church of the Nativity in Huntsville after her mother’s funeral there.

Tallulah and her sister Eugenia lived mainly with their grandparents in Jasper when Congress was not in session and the rest of the time with their aunt Marie Bankhead Owen and her husband, Thomas McAdory Owen, the first director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History in Montgomery. Beginning in 1916, the girls sometimes lived in adjacent apartments in Washington: Tallulah with her grandparents, and Eugenia with her father and stepmother Florence McGuire Bankhead, whom he had married in 1914. Their schooling was patchy: a mix of public, private, and boarding schools in Alabama, New York, and other locations. Not an eager student, Tallulah daydreamed about becoming a silent film star.

Eugenia and Tallulah Bankhead

In 1917, at age 15, Bankhead entered a Picture Play movie magazine contest to win a screen test. She shrewdly omitted her name from her application, hoping that the judges would wonder at her identity and extend the suspense through the magazine’s next issue. Her ruse worked, she won the screen test, and her father reluctantly allowed her to travel to New York, chaperoned by her aunt, Louise Bankhead Perry Lund. There, she lived in the Algonquin Hotel and won bit parts in six silent films and a few Broadway plays, with her father signing her contracts.

Eugenia and Tallulah Bankhead

In 1917, at age 15, Bankhead entered a Picture Play movie magazine contest to win a screen test. She shrewdly omitted her name from her application, hoping that the judges would wonder at her identity and extend the suspense through the magazine’s next issue. Her ruse worked, she won the screen test, and her father reluctantly allowed her to travel to New York, chaperoned by her aunt, Louise Bankhead Perry Lund. There, she lived in the Algonquin Hotel and won bit parts in six silent films and a few Broadway plays, with her father signing her contracts.

In 1923, she debuted on the London stage in The Rope Dancers. During the next eight years, she appeared in a dozen mostly mediocre plays. The exception was the 1926 London production of Sidney Coe Howard’s 1925 Pulitzer Prize-winning play They Knew What They Wanted, for which Tallulah’s portrayal of waitress Amy was acclaimed. Her beauty, wit, outrageous behavior (such as shouting obscenities at Nazis during a boxing match in Germany between German boxer Max Schmeling and fellow Alabamian Joe Louis), numerous relationships, and daring costumes made her a notorious celebrity, the epitome of the freewheeling Jazz Age. She became the toast of the London stage and one of the few individuals in England to be recognized only by her given name.

In 1931, with the English theater suffering from major financial difficulties during the Great Depression and the American talking-picture industry expanding, Tallulah returned to the United States under contract to Paramount Pictures. During the next two years, she starred in six mediocre films for Paramount, filming first in New York and then at the company’s new Hollywood studios. She starred with major Hollywood names, including Charles Laughton, Gary Cooper, and a young Cary Grant, in the 1932 film Devil and the Deep, but the poorly written script and overly melodramatic plot left audiences cold.

In 1934, she returned to the theater and during the next five years performed in several plays, again mostly mediocre in quality. Although producer David O. Selznick was interested in having her play Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind, she was judged too old, at age 34, to play the young belle. In 1937, she married actor John Emery at her grandmother’s home, Sunset, in Jasper. The marriage did not last, and the couple were divorced in 1941. They had no children. During the marriage, Bankhead starred unsuccessfully with Emery, a trained Shakespearean actor, in Antony and Cleopatra.

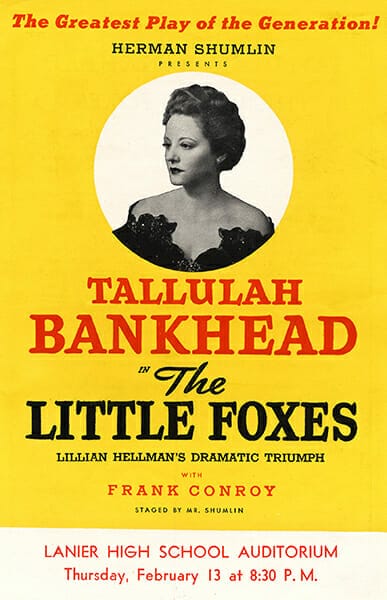

The Little Foxes

In 1939, she received the part of a lifetime, inaugurating the role of Regina Hubbard Giddings in Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes. Hellman’s melodrama reflects the lives of her well-to-do relatives in Demopolis at the turn of the twentieth century. For her portrayal, Tallulah won the New York Drama Critics Award for Best Performance. Life magazine’s March 6, 1939, picture story on the play included a cover photograph of Tallulah as Regina Giddings. After the play closed on Broadway, Bankhead and the cast spent the following year touring the United States. In 1942, she won another New York Drama Critics Award for Best Performance and Variety magazine’s Actress of the Year award for the role of Sabina in Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play The Skin of Our Teeth. Again, she toured the country with the play after its Broadway run.

The Little Foxes

In 1939, she received the part of a lifetime, inaugurating the role of Regina Hubbard Giddings in Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes. Hellman’s melodrama reflects the lives of her well-to-do relatives in Demopolis at the turn of the twentieth century. For her portrayal, Tallulah won the New York Drama Critics Award for Best Performance. Life magazine’s March 6, 1939, picture story on the play included a cover photograph of Tallulah as Regina Giddings. After the play closed on Broadway, Bankhead and the cast spent the following year touring the United States. In 1942, she won another New York Drama Critics Award for Best Performance and Variety magazine’s Actress of the Year award for the role of Sabina in Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play The Skin of Our Teeth. Again, she toured the country with the play after its Broadway run.

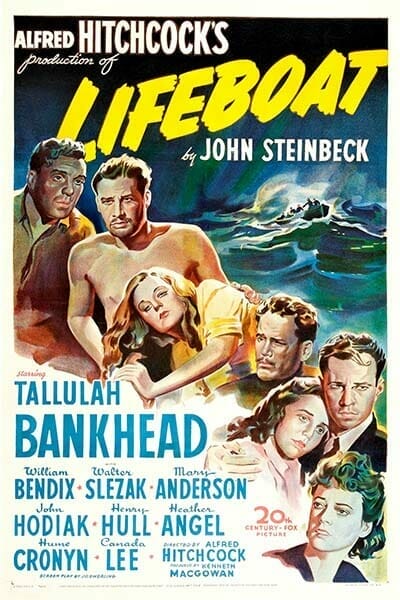

Movie Bill for Lifeboat

In 1944, director Alfred Hitchcock chose Bankhead to play the cynical journalist Constance Porter in his film Lifeboat, adapted from a John Steinbeck short story. She was awarded the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress for the role. Because Bankhead was no longer under long-term contract to a Hollywood studio, she was not nominated for an Oscar, but the film received Academy Award nominations for Best Cinematography in Black and White, Best Writing for an Original Story, and Best Director.

Movie Bill for Lifeboat

In 1944, director Alfred Hitchcock chose Bankhead to play the cynical journalist Constance Porter in his film Lifeboat, adapted from a John Steinbeck short story. She was awarded the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress for the role. Because Bankhead was no longer under long-term contract to a Hollywood studio, she was not nominated for an Oscar, but the film received Academy Award nominations for Best Cinematography in Black and White, Best Writing for an Original Story, and Best Director.

After World War II, Bankhead returned to the stage. Her many appearances included a long, very successful run in an updated 1948 revival of Noel Coward’s Private Lives, which also toured the United States after closing on Broadway. On November 13, 1948, Time magazine enthusiastically reviewed the play and featured Bankhead on its cover. In 1950, at age 48, with interesting female roles hard to come by, Bankhead reinvented herself as a radio personality and emcee of the award-winning NBC radio program The Big Show. The Sunday-night variety program aired from 1950 to 1952 but was discontinued as advertisers shifted to network television. The Big Show’s blend of comedy and performances by guest stars was enlivened by Bankhead’s unbridled enthusiasm, good-natured interactions with guests, and ready wit (assisted by Jane and Goodman Ace, two of the best writers in the business). Notable friends who performed with her included Fred Allen, Fanny Brice, Groucho Marx, Ethel Merman, Jimmy Durante, the comedy team of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Judy Garland, Ethel Barrymore, Margaret Truman, and Louis Armstrong. After The Big Show ended, Bankhead was among the first guests on the many television variety shows that replaced it.

Tallulah Bankhead Filming Batman

Riding on the success of The Big Show, which had made her known to millions of radio listeners across the nation, Bankhead published her autobiography, which sold 10 million copies and was a selection of the Sears Readers Book Club and a New York Times bestseller for 26 weeks. Bankhead publicized the book with a national tour and night-club appearances. She wowed audiences with her one-liners and breezy celebrity. After the book tour, Bankhead continued to perform on stage and television. Cameo appearances as herself in the 1957 episode “The Celebrity Next Door” on The Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz Show, and as the Black Widow in the 1960s Batman series have become cult classics. Her last theatrical appearance was in Tennessee Williams’ play The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Any More in 1963. Her last film was the 1965 British horror movie, Die! Die! My Darling!. Her last television appearance was as the Black Widow in the Batman series in 1967.

Tallulah Bankhead Filming Batman

Riding on the success of The Big Show, which had made her known to millions of radio listeners across the nation, Bankhead published her autobiography, which sold 10 million copies and was a selection of the Sears Readers Book Club and a New York Times bestseller for 26 weeks. Bankhead publicized the book with a national tour and night-club appearances. She wowed audiences with her one-liners and breezy celebrity. After the book tour, Bankhead continued to perform on stage and television. Cameo appearances as herself in the 1957 episode “The Celebrity Next Door” on The Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz Show, and as the Black Widow in the 1960s Batman series have become cult classics. Her last theatrical appearance was in Tennessee Williams’ play The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Any More in 1963. Her last film was the 1965 British horror movie, Die! Die! My Darling!. Her last television appearance was as the Black Widow in the Batman series in 1967.

Tallulah Bankhead and W. C. Handy

A little known aspect of Bankhead’s life is her work for racial tolerance and equality in America, especially in the performing arts and sports, after her return to the United States in 1931. When Alabama-born boxer Joe Louis knocked out German contestant Max Schmeling, the Nazi Party favorite, in a June 22, 1938, rematch, Bankhead leapt to her feet, shouting approval. An avid baseball fan in the 1940s and 1950s, she cheered fellow Alabamians Willie Mays and Willie McCovey, members of the then-New York Giants, her favorite team. She also became a friend and supporter of musicians W. C. Handy (a fellow Alabamian), Louis Armstrong, and Billie Holliday. In the early 1950s, she helped support Handy in his attempt to organize a fund supporting young black musicians. Armstrong joined her as a guest on The Big Show in its second week and was among several African Americans to appear on the show, including performers Ella Fitzgerald, Ethel Waters, Josephine Baker, the Ink Spots, and political scientist and diplomat Ralph Bunche.

Tallulah Bankhead and W. C. Handy

A little known aspect of Bankhead’s life is her work for racial tolerance and equality in America, especially in the performing arts and sports, after her return to the United States in 1931. When Alabama-born boxer Joe Louis knocked out German contestant Max Schmeling, the Nazi Party favorite, in a June 22, 1938, rematch, Bankhead leapt to her feet, shouting approval. An avid baseball fan in the 1940s and 1950s, she cheered fellow Alabamians Willie Mays and Willie McCovey, members of the then-New York Giants, her favorite team. She also became a friend and supporter of musicians W. C. Handy (a fellow Alabamian), Louis Armstrong, and Billie Holliday. In the early 1950s, she helped support Handy in his attempt to organize a fund supporting young black musicians. Armstrong joined her as a guest on The Big Show in its second week and was among several African Americans to appear on the show, including performers Ella Fitzgerald, Ethel Waters, Josephine Baker, the Ink Spots, and political scientist and diplomat Ralph Bunche.

In the 1948 presidential election, she campaigned for Democratic candidate Harry S. Truman, who vowed, if elected, to integrate the U.S. military. When introducing him on nationwide radio on October 21, 1948, she noted that Truman was, “the partisan of our troubled millions,” which listeners understood as the nation’s African Americans. After Truman won the election, Bankhead was invited to sit with the president’s family during his inauguration. From the presidential reviewing stand, she loudly booed strident segregationist and then-governor of South Carolina Strom Thurmond when his float passed by.

Tallulah Bankhead Star in Birmingham

In December 1952, Bankhead wrote an article for Ebony magazine, “The World’s Greatest Musician,” in which she honored her friend Louis Armstrong, comparing him favorably to William Shakespeare. In January 1960, she contributed “A Southerner Looks at Prejudice” to Ebony and reminded readers that racial equality was long overdue, that talent has no color line, and that racial discrimination was not just the South’s problem, but America’s problem. Tallulah Bankhead died on December 12, 1968, of pneumonia complicated by emphysema and her long addiction to smoking. She was buried in St. Paul’s Churchyard, Chestertown, Maryland, in her sister Eugenia’s family plot.

Tallulah Bankhead Star in Birmingham

In December 1952, Bankhead wrote an article for Ebony magazine, “The World’s Greatest Musician,” in which she honored her friend Louis Armstrong, comparing him favorably to William Shakespeare. In January 1960, she contributed “A Southerner Looks at Prejudice” to Ebony and reminded readers that racial equality was long overdue, that talent has no color line, and that racial discrimination was not just the South’s problem, but America’s problem. Tallulah Bankhead died on December 12, 1968, of pneumonia complicated by emphysema and her long addiction to smoking. She was buried in St. Paul’s Churchyard, Chestertown, Maryland, in her sister Eugenia’s family plot.

Selected Works by Tallulah Bankhead

Tallulah: My Autobiography (1952)

“A Southerner Looks at Prejudice.” Ebony (January 1960)

“The World’s Greatest Musician.” Ebony (December 1952)

Further Reading

- Bashaw, Carolyn Terry. “‘I shall make good big’: The Algonquian Correspondence of Tallulah Bankhead, 1918-1920.” Alabama Review 54 (October 2001): 277-299.

- Carrier, Jeffry L. Tallulah Bankhead: A Bio-Bibliography. New York: Greenwood Press, 1991.

- Gill, Brendan. Tallulah. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1972.

- Lobenthal, Joel. Tallulah! The Life and Times of a Leading Lady. New York: HarperEntertainment, 2004.