Viola Gregg Liuzzo

Viola Gregg Liuzzo

Viola Liuzzo (1925-1965) was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan on the last night of the 1965 Selma Voting Rights March. She is the only white woman honored at the Montgomery Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery. Remembered primarily for the atmosphere of scandal surrounding her death created by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), she is considered the most controversial of the civil rights martyrs.

Viola Gregg Liuzzo

Viola Liuzzo (1925-1965) was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan on the last night of the 1965 Selma Voting Rights March. She is the only white woman honored at the Montgomery Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery. Remembered primarily for the atmosphere of scandal surrounding her death created by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), she is considered the most controversial of the civil rights martyrs.

Viola Gregg was born on April 11, 1925, in California, Pennsylvania. She was raised in rural Georgia and Tennessee and attended segregated schools. During World War II, she moved with her family to Ypsilanti, Michigan, where she worked at Ford’s Willow Run Bomber Plant. At 18 she moved on to Detroit, found employment as a waitress, married restaurant manager George Argyris in 1943 and had two daughters. In 1949 Liuzzo divorced Argyris and the following year married Anthony James Liuzzo, a Teamsters Union organizer, with whom she had two sons and another daughter.

By 1965 Liuzzo was a 39-year-old, middle-class housewife and mother of five. After her youngest child started school, she enrolled as a part-time student at Wayne State University and was inspired by returning students’ reports about the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer project to register black voters. In March 1965, she participated in sympathy marches to demonstrate solidarity with Black citizens in Selma, Alabama, who were planning a pilgrimage to the state capitol to support passage of a federal voting-rights bill.

On March 7, 1965, Liuzzo watched news broadcasts of state troopers armed with billy clubs and tear gas attack 600 demonstrators crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge on their way to Montgomery. Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. called off the attempt and issued a national appeal for Americans to come to Selma, join the marchers, and help them try again. Liuzzo and 25,000 other Americans answered his call.

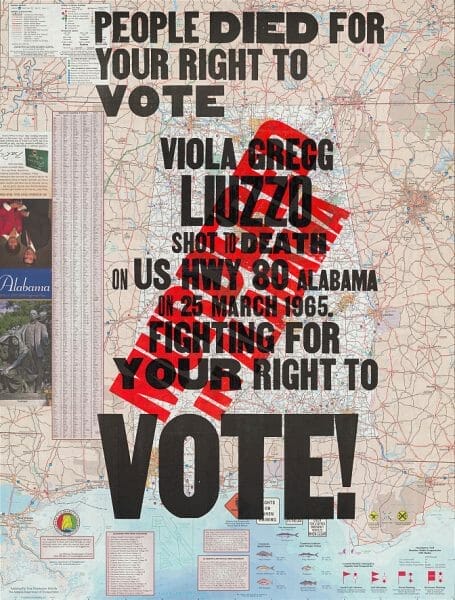

For five days, Liuzzo worked for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference‘s (SCLC) transportation service ferrying marchers between Selma and Montgomery. On March 25, she and Leroy Moton, a 19-year-old local black activist, headed to Montgomery to pick up the last group of demonstrators waiting to return to Selma. While stopped at a traffic light in front of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, at 7:37 p.m., they were spotted by four Klansmen who, according to the later testimony of one of them, had spent the day seeking an opportunity to kill King. When they saw the white Liuzzo driving a car with Michigan plates after dark with a black man in her passenger seat, they decided to attack them instead. The Klansmen hoped that this would send a clear message about white supremacy to northern whites, southern blacks, and like-minded liberals. Engaging Liuzzo in a high-speed chase on Highway 80, they pulled alongside her car about 20 miles outside of Selma and fired. Liuzzo was killed instantly and Moton, covered in her blood, escaped by pretending to be dead.

Within 24 hours, the FBI had taken four suspects into custody, and Pres. Lyndon Johnson praised the bureau for its excellent work. Collie LeRoy Wilkins, 21; William Orville Eaton, 41; Eugene Thomas, 42; and Gary Thomas Rowe, 42, were indicted on April 6, 1965. Nine days later, all charges against Rowe were dropped, and he was identified as a paid undercover FBI informant who would testify for the prosecution.

While Liuzzo was being honored as a martyr, Bureau Director J. Edgar Hoover was increasingly concerned about the embarrassing fact that Rowe had telephoned his FBI contact on March 25 and received permission to “work” during the march despite his history of violent behavior toward civil-rights activists. Rowe had participated in the beatings of Freedom Riders in Birmingham in 1961 and was suspected of involvement in the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. In order to deflect criticism, Hoover shifted the focus of the national news coverage from the FBI to Liuzzo’s motivation for joining the march. He consistently referred to her as an “outside agitator,” despite her southern upbringing, and at a private meeting with President Johnson reported that Liuzzo’s husband Jim was a Teamsters organizer with “a shady background.” Hoover also suggested that Liuzzo and Moton had stopped for a romantic interlude. When the president ignored his innuendos, Hoover instructed FBI staff to leak his speculations to the bureau’s Klan informants, who subsequently leaked them to the press. Liuzzo was widely portrayed in the media as an unstable woman who had abandoned her family to cause trouble in the South.

On May 3, 1965, the trial of Collie Leroy Wilkins, alleged by the prosecution to be the trigger man in the Liuzzo murder, began in Hayneville, Lowndes County. Defense attorney Matthew Hobson Murphy Jr., Grand Klonsel of the United Klans of America, informed the jury that since Rowe had broken his Klan loyalty oath by testifying against his fellow Klansmen they should not believe anything he said, and that Liuzzo was a white woman alone in a car with a black man at night and whatever happened to her was her own fault. Murphy was successful in his attempts to blame Liuzzo for her own fate, and the trial ended in a hung jury. In subsequent trials, Alabama juries cleared Wilkins, Eaton, and Thomas, but federal juries convicted them of violating Liuzzo’s civil rights and sentenced them to 10 years in prison. Eaton, died in March 1966 before beginning his sentence, whereas Rowe was granted full immunity and placed in the federal witness protection program.

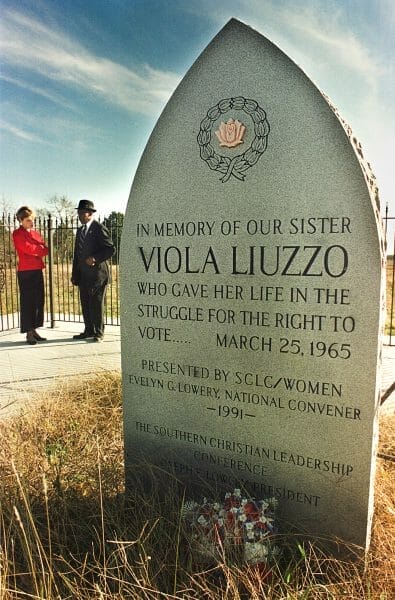

Viola Liuzzo Memorial Marker

Liuzzo’s murder moved President Johnson to order a federal investigation of the Klan and to petition Congress to expand the Federal Conspiracy Act of 1870 to make murder of civil rights activists a federal crime. Her death increased congressional support for the passage of the Voting Rights Act, which Johnson signed on August 6, 1965. But the false accusations about Liuzzo devastated her family. Until they obtained her FBI file through the Freedom of Information Act in 1977, they didn’t know that the ugly slander about their mother had originated in the offices of the U.S. Justice Department. In December 1977, the family filed a $2 million negligence claim against the federal government, charging that the FBI knew that Rowe and his fellow Klansmen were planning violence on March 25, 1965, and by doing nothing to prevent it had effectively conspired in her murder. When Collie Leroy Wilkins and Eugene Thomas were subsequently subpoenaed to testify before a Lowndes County grand jury, they insisted that Rowe had shot her. Both passed lie-detector tests, and two Birmingham police officers later admitted that Rowe had also bragged to them that he’d killed Liuzzo. In September 1978, Rowe was indicted for first-degree murder. Government attorneys, however, successfully moved to dismiss the charge based on his 1965 immunity.

Viola Liuzzo Memorial Marker

Liuzzo’s murder moved President Johnson to order a federal investigation of the Klan and to petition Congress to expand the Federal Conspiracy Act of 1870 to make murder of civil rights activists a federal crime. Her death increased congressional support for the passage of the Voting Rights Act, which Johnson signed on August 6, 1965. But the false accusations about Liuzzo devastated her family. Until they obtained her FBI file through the Freedom of Information Act in 1977, they didn’t know that the ugly slander about their mother had originated in the offices of the U.S. Justice Department. In December 1977, the family filed a $2 million negligence claim against the federal government, charging that the FBI knew that Rowe and his fellow Klansmen were planning violence on March 25, 1965, and by doing nothing to prevent it had effectively conspired in her murder. When Collie Leroy Wilkins and Eugene Thomas were subsequently subpoenaed to testify before a Lowndes County grand jury, they insisted that Rowe had shot her. Both passed lie-detector tests, and two Birmingham police officers later admitted that Rowe had also bragged to them that he’d killed Liuzzo. In September 1978, Rowe was indicted for first-degree murder. Government attorneys, however, successfully moved to dismiss the charge based on his 1965 immunity.

At the same time, the government refused to negotiate the Liuzzo’s negligence claim, and the family filed a formal suit in 1979. This case was tried in an Ann Arbor, Michigan, federal district court in 1983 without the benefit of a jury, who might have been sympathetic. On May 27, Judge Charles W. Joiner dismissed it, ruling that there was no evidence of an FBI conspiracy to cause Liuzzo’s death. The case was considered a test of the FBI’s obligation to protect citizens and was constitutionally significant for future civil-rights litigation.

The 1965 murder of Viola Liuzzo engaged the nation in a heated debate about a woman’s obligations to her family and to society at large. Liuzzo had violated traditional cultural boundaries to demonstrate on behalf of black civil rights, a movement that a majority of white Americans believed was too aggressive. It took almost a quarter century to formally recognize Liuzzo’s efforts. In 1989, she became one of 40 civil-rights martyrs whose lives were commemorated on the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery. In 1991, the Women of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference erected a stone marker on Highway 80 at the spot where she was murdered. It is inscribed “In memory of our sister Viola Liuzzo who gave her life in the struggle for the right to vote March 25, 1965.” The monument has been and continues to be the subject of vandalism.

Further Reading

- Stanton, Mary. From Selma To Sorrow: The Life and Death of Viola Liuzzo. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1998.