Choctaws in Alabama

Choctaw Stickball Player

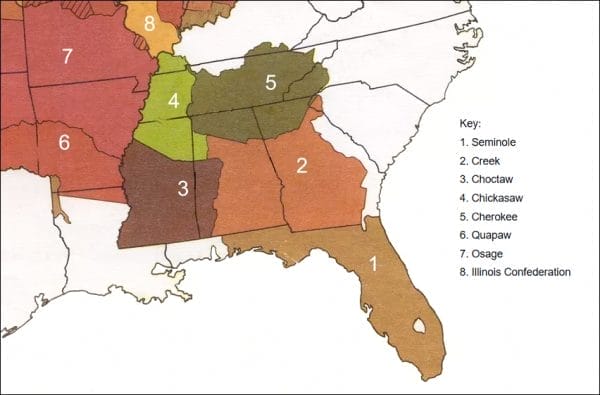

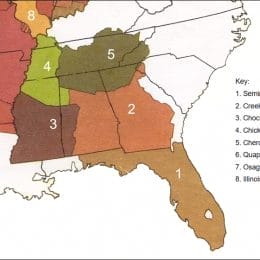

The Choctaw Indians once lay claim to millions of acres of land and established some 50 towns in present-day Mississippi and western Alabama. With a population of at least 15,000 by the turn of the nineteenth century, the Choctaws were one of the largest Indian groups in the South and played a significant role in shaping the politics, economics, and armed conflicts in the region. Thousands of Choctaws remained in the Southeast even after removal and are known today as the federally recognized Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and the state-recognized MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians (so named for their location in Mobile and Washington County) Choctaws of Alabama. Other Choctaw people live in the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, in Choctaw communities in Texas and Tennessee, and as families or individuals throughout the United States.

Choctaw Stickball Player

The Choctaw Indians once lay claim to millions of acres of land and established some 50 towns in present-day Mississippi and western Alabama. With a population of at least 15,000 by the turn of the nineteenth century, the Choctaws were one of the largest Indian groups in the South and played a significant role in shaping the politics, economics, and armed conflicts in the region. Thousands of Choctaws remained in the Southeast even after removal and are known today as the federally recognized Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and the state-recognized MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians (so named for their location in Mobile and Washington County) Choctaws of Alabama. Other Choctaw people live in the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, in Choctaw communities in Texas and Tennessee, and as families or individuals throughout the United States.

The peoples who became known as the Choctaws (they call themselves Chahtas) originally lived as separate societies throughout east-central Mississippi and west-central Alabama and all spoke dialects of the Muskogean language. From at least the eighteenth century, there existed among the Choctaws a confederacy of three principal geographic and political groups: the western, eastern, and Six Towns (or southern). The villages of the western division were scattered around the upper Pearl River watershed in east-central Mississippi; the eastern division towns were located around the upper Chickasawhay River and lower Tombigbee River watersheds along the lower Alabama-Mississippi border; and the Six Towns were distributed along the upper Leaf River and mid-Chickasawhay River watersheds in southeast Mississippi.

Predecessors

The members of the eastern division may have descended from the Mississippian peoples of the Moundville chiefdom of west-central Alabama around present-day Tuscaloosa. The western peoples lived historically among the headwaters of the Upper Pearl River, and the Six Towns descended from peoples who lived in the southern and southwest regions of Mississippi. These independent societies likely first moved near each other sometime after Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto’s expedition through the southeastern United States in the early 1540s and before 1699, when the French arrived on the Gulf Coast. Each village within the division maintained its own chiefs and other leaders well into the nineteenth century. The eastern Choctaws also maintained a close ethnic and cultural relationship with the Alabama Indians, who lived at the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers. One prominent eastern-division Choctaw chief of the eighteenth century, for example, was named Alibamon Mingo (meaning Alabama chief) and may have had kinship ties to the Alabamas.

Choctaw Baskets

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, various Creek villages and the Chickasaws repeatedly attacked the Choctaws to seize captives for sale as slaves to British planters in South Carolina. Indian societies throughout the Southeast traditionally warred against one another for a variety of reasons before and after Europeans arrived on the continent. The Creeks and Chickasaws used the firearms they acquired from trade with the British to capture as many as 2,000 Choctaws, who were then sold to work on sugar plantations in the British West Indies. When the French, under Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, established the Louisiana colony at present-day Biloxi, Mississippi, in 1699, the Choctaws quickly established political and trade connections with them to acquire guns and fight off slave raiders. Choctaws assisted French forces in attacking the Natchez Indians after the Natchez Revolt of 1729, and the Choctaws joined the French on several attacks against the Chickasaws.

Choctaw Baskets

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, various Creek villages and the Chickasaws repeatedly attacked the Choctaws to seize captives for sale as slaves to British planters in South Carolina. Indian societies throughout the Southeast traditionally warred against one another for a variety of reasons before and after Europeans arrived on the continent. The Creeks and Chickasaws used the firearms they acquired from trade with the British to capture as many as 2,000 Choctaws, who were then sold to work on sugar plantations in the British West Indies. When the French, under Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, established the Louisiana colony at present-day Biloxi, Mississippi, in 1699, the Choctaws quickly established political and trade connections with them to acquire guns and fight off slave raiders. Choctaws assisted French forces in attacking the Natchez Indians after the Natchez Revolt of 1729, and the Choctaws joined the French on several attacks against the Chickasaws.

Choctaw Civil War

Not all Choctaws wanted to trade only with France, however. Renowned Choctaw war leader Red Shoes, who hailed from the western division, opened trade with British fur traders based in South Carolina in the 1740s and ignited the Choctaw Civil War when he killed some French traders. Rivalries over trade with France and Britain caused the rift in Choctaw society, primarily between the western and eastern divisions, that lasted from 1747 to 1750. Eastern-division forces allied with France prevailed in the conflict and burned several western-division towns to the ground. Hundreds of Choctaws died during the war, which revealed deep divisions in the confederacy. After the conflict, Choctaw leaders worked to end inter-ethnic animosities and unite their peoples more closely.

After the civil war, some Choctaw towns and individuals continued to seek a trading relationship with Britain. Such independence was encouraged under the non-coercive leadership traditions of the Choctaws and other southeastern Indian groups. Because some Choctaw towns traded mostly with Britain while others traded primarily with France, the Choctaws, though not acting under any centralized national government, were nonetheless able to play the two European countries against each other, strengthening their hand in foreign diplomacy. Choctaws and their chiefs acquired European manufactured items, such as essential guns and wool cloth, by trading deerskins and other items to fur traders. The Choctaws who traded with Britain came out ahead when the French and Indian War broke out in the late 1750s, and French supply ships failed to arrive. Relations between eastern-division Choctaws and the French remained strong, however, until the French vacated the South after the conflict ended in 1763. All southeastern Indians thus opened or strengthened trade with Britain, and in 1765, tribal leaders representing the Choctaws and Chickasaws met with British negotiator and former French officer Henrí Montault de Monbéraut de Saint-Çivier in Mobile under the auspices of George Johnstone, governor of British West Florida, and signed the Treaty with the Choctaws and Chickasaws. These close relations remained intact after that war and through the subsequent American Revolutionary War. Most Choctaws who participated in the war defended British posts at Natchez, Mobile, and Pensacola against American and Spanish attacks, though some members of the Six Towns division supported Spanish military efforts against Britain.

Post-Revolution

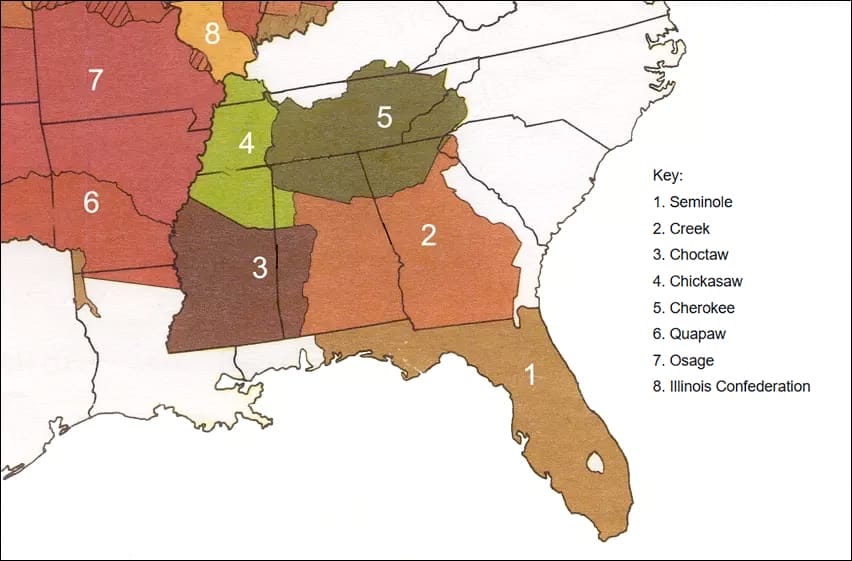

Choctaw Land Cessions in Mississippi and Alabama

After the American Revolution, Choctaws were forced to seek new trade sources and soon established relations with the United States and Spain (which gained control of the entire Gulf Coast after the war). The Choctaws appealed to Spain at a treaty meeting in Mobile in 1784 to open trade, and in 1786 the Choctaws signed their first treaty with the United States to establish trade. In the late 1790s, Spain transferred their claims on Choctaw lands to the United States, leaving the Choctaws with only the United States as a major trading partner by the turn of the century. Because deer herds had become depleted and European American demand for deerskins had dropped, Choctaws sought new ways to make money to purchase the trade items they had long since come to need. Thus, some Choctaws, especially those whose families included European American fur traders, entered the emerging market economy of early-nineteenth-century America by raising and selling livestock and horses, cultivating cotton with enslaved African American labor, operating inns and ferries, and marketing food products, baskets, and other sundry items. Despite their success at assimilating into mainstream American society and forming profitable businesses, the Choctaws repeatedly were forced to fend off state and federal officials’ demands for their land. In 1801, the Choctaws signed what would be the first of many land cessions with the United States. In the Fort Confederation Treaty of 1802, the Choctaws ceded the southwest portion of present-day Alabama north of the 31st line of latitude. The Mount Dexter Treaty of 1805 ceded another sizable area of land bordering the northern boundary of the Fort Confederation cession.

Choctaw Land Cessions in Mississippi and Alabama

After the American Revolution, Choctaws were forced to seek new trade sources and soon established relations with the United States and Spain (which gained control of the entire Gulf Coast after the war). The Choctaws appealed to Spain at a treaty meeting in Mobile in 1784 to open trade, and in 1786 the Choctaws signed their first treaty with the United States to establish trade. In the late 1790s, Spain transferred their claims on Choctaw lands to the United States, leaving the Choctaws with only the United States as a major trading partner by the turn of the century. Because deer herds had become depleted and European American demand for deerskins had dropped, Choctaws sought new ways to make money to purchase the trade items they had long since come to need. Thus, some Choctaws, especially those whose families included European American fur traders, entered the emerging market economy of early-nineteenth-century America by raising and selling livestock and horses, cultivating cotton with enslaved African American labor, operating inns and ferries, and marketing food products, baskets, and other sundry items. Despite their success at assimilating into mainstream American society and forming profitable businesses, the Choctaws repeatedly were forced to fend off state and federal officials’ demands for their land. In 1801, the Choctaws signed what would be the first of many land cessions with the United States. In the Fort Confederation Treaty of 1802, the Choctaws ceded the southwest portion of present-day Alabama north of the 31st line of latitude. The Mount Dexter Treaty of 1805 ceded another sizable area of land bordering the northern boundary of the Fort Confederation cession.

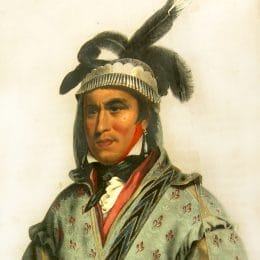

Pushmataha

Besides attempting to participate successfully in the American economy, Choctaws supported American goals in other ways after the American Revolution. During the Creek War of 1813-14, the Choctaws, under the leadership of Chief Pushmataha, joined forces with Americans under Andrew Jackson to put down the Red Stick Creek rebellion, including participation in the Battles of Econochaca (Holy Ground) and Horseshoe Bend. A few hundred Choctaws from the Six Towns division supported the aims of the Red Stick Creeks and moved to southeast Alabama to escape retaliation from the Americans and Pushmataha. Despite their efforts in support of American foreign policy, the U.S. government insisted on additional land cessions in the 1816 Treaty of Fort St. Stephens, which transferred millions of acres of Choctaw land in Alabama, including present-day Tuscaloosa, to the United States. Beginning in 1819, Choctaws welcomed Congregationalist and Presbyterian missionaries from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions into the Choctaw nation to teach English, basic math, advanced farming techniques, and other business-related skills. By 1826, with the help of the missionaries, the Choctaws produced a written constitution that established a representative form of government that elected three principal chiefs (one from each division), a formal system of education, and a police force. U.S. officials had been urging these changes for many years. According to the 1820 Treaty of Doak’s Stand, the Choctaws were required to remove west to lands in Arkansas, but those lands had already been occupied by white Americans. Pushmataha and other Choctaw chiefs travelled to Washington, D.C., in 1824 in the hope of changing the treaty’s stipulations, but Pushmataha died before that was accomplished. He was buried there in Congressional Cemetery.

Pushmataha

Besides attempting to participate successfully in the American economy, Choctaws supported American goals in other ways after the American Revolution. During the Creek War of 1813-14, the Choctaws, under the leadership of Chief Pushmataha, joined forces with Americans under Andrew Jackson to put down the Red Stick Creek rebellion, including participation in the Battles of Econochaca (Holy Ground) and Horseshoe Bend. A few hundred Choctaws from the Six Towns division supported the aims of the Red Stick Creeks and moved to southeast Alabama to escape retaliation from the Americans and Pushmataha. Despite their efforts in support of American foreign policy, the U.S. government insisted on additional land cessions in the 1816 Treaty of Fort St. Stephens, which transferred millions of acres of Choctaw land in Alabama, including present-day Tuscaloosa, to the United States. Beginning in 1819, Choctaws welcomed Congregationalist and Presbyterian missionaries from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions into the Choctaw nation to teach English, basic math, advanced farming techniques, and other business-related skills. By 1826, with the help of the missionaries, the Choctaws produced a written constitution that established a representative form of government that elected three principal chiefs (one from each division), a formal system of education, and a police force. U.S. officials had been urging these changes for many years. According to the 1820 Treaty of Doak’s Stand, the Choctaws were required to remove west to lands in Arkansas, but those lands had already been occupied by white Americans. Pushmataha and other Choctaw chiefs travelled to Washington, D.C., in 1824 in the hope of changing the treaty’s stipulations, but Pushmataha died before that was accomplished. He was buried there in Congressional Cemetery.

Choctaw Removal

MOWA Pow Wow

On September 27, 1830, the Choctaw government ceded all lands east of the Mississippi River, including the last portion of Choctaw lands in Alabama along the Mississippi border, in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Alabama pioneer George Strothers Gaines organized and oversaw the Choctaw removal in the winter of 1831-32. Despite great personal financial loss, Gaines later looked back with pride at the fact that the majority of the Choctaws who left Mississippi that winter under his supervision remained fed, clothed, and healthy. Most Choctaws were forcibly removed to Indian Territory (now present-day Oklahoma) beginning in 1831, but a few thousand remained in Mississippi and Alabama. Today, their descendants belong to the present-day Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians, respectively. The MOWA Choctaws claim to be descended from those Six Towns Choctaws who joined the Red Stick Creeks during the Creek War and then hid in the swamps and forests of southwest Alabama to avoid attacks by the Americans and Choctaws under Pushmataha. Despite a lengthy documentary and cultural record detailing their continued presence in Alabama, the MOWA Choctaws enjoy only state-level tribal recognition.

MOWA Pow Wow

On September 27, 1830, the Choctaw government ceded all lands east of the Mississippi River, including the last portion of Choctaw lands in Alabama along the Mississippi border, in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Alabama pioneer George Strothers Gaines organized and oversaw the Choctaw removal in the winter of 1831-32. Despite great personal financial loss, Gaines later looked back with pride at the fact that the majority of the Choctaws who left Mississippi that winter under his supervision remained fed, clothed, and healthy. Most Choctaws were forcibly removed to Indian Territory (now present-day Oklahoma) beginning in 1831, but a few thousand remained in Mississippi and Alabama. Today, their descendants belong to the present-day Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians, respectively. The MOWA Choctaws claim to be descended from those Six Towns Choctaws who joined the Red Stick Creeks during the Creek War and then hid in the swamps and forests of southwest Alabama to avoid attacks by the Americans and Choctaws under Pushmataha. Despite a lengthy documentary and cultural record detailing their continued presence in Alabama, the MOWA Choctaws enjoy only state-level tribal recognition.

Further Reading

- Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

- Carson, James Taylor. Searching for the Bright Path: The Mississippi Choctaws from Prehistory to Removal. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

- DeRosier, Arthur H., Jr. The Removal of the Choctaw Indians. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1970.

- Gaines, George Strother. The Reminiscences of George Strother Gaines: Pioneer and Statesman of Early Alabama and Mississippi, 1805-1843. Edited by James P. Pate. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998.

- Galloway, Patricia. Choctaw Genesis, 1500-1700. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

- Kidwell, Clara Sue. Choctaws and Missionaries in Mississippi, 1818-1918. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

- Lincecum, Gideon. Pushmataha: A Choctaw Leader and His People. Introduction by Greg O’Brien. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Matte, Jacqueline Anderson. “Extinction by Reclassification: The MOWA Choctaws of South Alabama and Their Struggle for Federal Recognition.” Alabama Review 59 (July 2006): 163-204.

- ———. They Say the Wind is Red: The Alabama Choctaw—Lost in Their Own Land. Red Level, Ala.: Greenberry Publishing Company, 1999.

- O’Brien, Greg. Choctaws in a Revolutionary Age, 1750-1830. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

- Young, Mary Elizabeth. Redskins, Ruffleshirts, and Rednecks: Indian Allotments in Alabama and Mississippi, 1830-1860. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961.