Mississippian Period

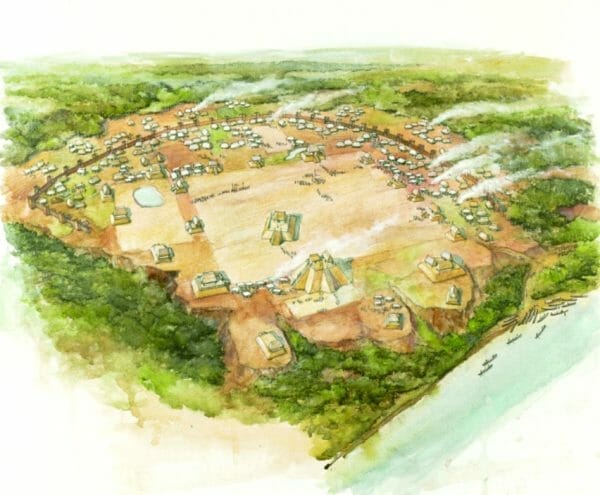

Moundville Reconstruction

The Mississippian period (AD 1000-1550) marked a new way of life for Native Americans in what is now the midwestern and southeastern United States. Prior to this time, people in those regions gathered wild foods and supplemented them with produce from small garden plots. Most communities were small. About 1,000 years ago, this older way of life changed as communities grew in size. Mississippian culture was not a single “tribe,” but many societies sharing a similar way of life or tradition. Mississippian peoples lived in fortified towns or small homesteads, grew corn, built large earthen mounds, maintained trade networks, had powerful leaders, and shared similar symbols and rituals. The term “Mississippian” comes from the Mississippi River Valley, where the tradition first developed. Through borrowed ideas and migrations of people, this new tradition spread across the Southeast, appearing in what is now Alabama around AD 1100. Because the Mississippians left no written record, what we know of this time period has been learned through archaeology.

Moundville Reconstruction

The Mississippian period (AD 1000-1550) marked a new way of life for Native Americans in what is now the midwestern and southeastern United States. Prior to this time, people in those regions gathered wild foods and supplemented them with produce from small garden plots. Most communities were small. About 1,000 years ago, this older way of life changed as communities grew in size. Mississippian culture was not a single “tribe,” but many societies sharing a similar way of life or tradition. Mississippian peoples lived in fortified towns or small homesteads, grew corn, built large earthen mounds, maintained trade networks, had powerful leaders, and shared similar symbols and rituals. The term “Mississippian” comes from the Mississippi River Valley, where the tradition first developed. Through borrowed ideas and migrations of people, this new tradition spread across the Southeast, appearing in what is now Alabama around AD 1100. Because the Mississippians left no written record, what we know of this time period has been learned through archaeology.

The Mississippian Tradition arose after people began devoting greater efforts to growing corn. This provided a surplus of storable food and allowed populations to increase. Settlements tended to concentrate in river valleys, with their good soils and abundant wild foods. Larger communities produced new forms of cooperation and competition. As a result of these changes, some people gained power or influence over others.

Daily Life

The Mississippians farmed, hunted, and fished. They grew corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers in plots worked by hand with shell or stone hoes. Farmers cleared fields by burning areas of forest, but because they used no fertilizer, they had to create new fields after a few growing seasons. This practice is still in use among some indigenous peoples of the world and is known as slash-and-burn agriculture. Nuts, acorns, and wild fruits supplemented the cultivated crops. With no domesticated animals except the dog, Mississippian people performed their own field labor and hunted wild game. Fish, deer, and turtles were important sources of protein.

Reconstructed Mississippian Compound

The Mississippians fashioned their tools from pottery, stone, wood, and shell. They chipped stone into arrow points, knives, and scrapers, or shaped stones into axes called celts and bone into awls and fishhooks. They processed plant foods on grinding stones or pounded them in wooden mortars with pestles. Gourd, basketry, and earthenware pottery containers held food and drink. Mississippian peoples cooked meals in kettle-shaped jars and served them in bowls, dishes, and bottles. Most of the pottery they made is plain and drab, but decoration on some pieces recovered by archaeologists includes incised and stamped designs, lustrous black finishes, and red, white, and black paint. Fine serving vessels display handles shaped like animal heads and tails. Some pots were made in the shapes of animal or human forms (effigies), as were some clay and stone smoking pipes. Archaeologists have also recovered a number of small clay disks, cut and shaped from pieces of broken pots. Their function is unknown, but they may have been gaming pieces or possibly spindle whorls for spinning yarn. They also played a game known as chunkey in which large stone disks were rolled along the ground and which Indian peoples still played in historic times.

Reconstructed Mississippian Compound

The Mississippians fashioned their tools from pottery, stone, wood, and shell. They chipped stone into arrow points, knives, and scrapers, or shaped stones into axes called celts and bone into awls and fishhooks. They processed plant foods on grinding stones or pounded them in wooden mortars with pestles. Gourd, basketry, and earthenware pottery containers held food and drink. Mississippian peoples cooked meals in kettle-shaped jars and served them in bowls, dishes, and bottles. Most of the pottery they made is plain and drab, but decoration on some pieces recovered by archaeologists includes incised and stamped designs, lustrous black finishes, and red, white, and black paint. Fine serving vessels display handles shaped like animal heads and tails. Some pots were made in the shapes of animal or human forms (effigies), as were some clay and stone smoking pipes. Archaeologists have also recovered a number of small clay disks, cut and shaped from pieces of broken pots. Their function is unknown, but they may have been gaming pieces or possibly spindle whorls for spinning yarn. They also played a game known as chunkey in which large stone disks were rolled along the ground and which Indian peoples still played in historic times.

Mississippian houses rotted away long ago, but archaeologists find remains of house walls and features in the form of square, rectangular, and circular soil stains. Most houses were small, one-room buildings barely large enough for two or three people to sleep in. Walls consisted of vertical logs, often set in foundation trenches, covered with cane wattles, grass thatch, or sometimes a mud-and-straw plaster (daub). Fireplace hearths were placed directly on the earthen floor or in clay-lined basins.

Studies of Mississippian skeletons in Alabama tell us much about the people’s lives and deaths. People were generally healthy and appear to have had adequate nutrition, but few people lived beyond age 50. Poor sanitation spread infections, and many infants died. Tuberculosis and arthritis afflicted some people. Almost everyone suffered from tooth decay resulting from their corn-based diet. Skeletons also show signs of violence. At small settlements, such as the Lubbub Creek site near Aliceville, many adult male skeletons display evidence of violent injury, probably inflicted in war. Examination of male and female skeletons recovered from the Koger’s Island and Perry sites on the Tennessee River near Florence indicate that the people were clubbed to death or shot with arrows and scalped. Some were buried in a mass grave, apparently the victims of a raid. People who lived at larger settlements had greater security. Of the hundreds of skeletons from the huge Moundville site on the Black Warrior River south of Tuscaloosa, few show any indications of violent deaths.

Social Organization, Moundbuilding, and Decorative Art

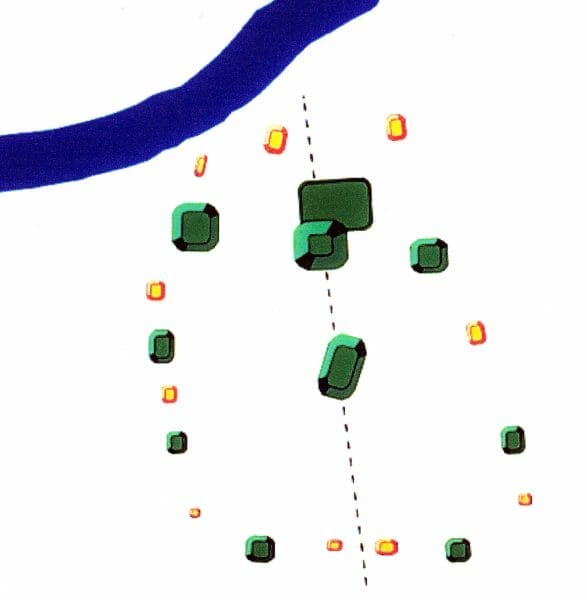

Moundville Diagram

Archaeologists believe that the Mississippian peoples were organized into chiefdoms, a form of political organization united under an official leader, or “chief.” Chiefdom societies were organized by families of differing social rank or status. Although people in chiefdoms inherited their rank at birth, they could gain prestige through personal achievement, as shown in the historical evidence. First, accounts of Mississippians in Alabama written by sixteenth-century Spanish explorers suggest chiefdoms were present at that time. These accounts mention powerful chiefs living in large capital towns marked by earthen mounds and protected by wooden palisades. Less powerful chiefs in smaller surrounding settlements paid tribute to their capital town. Second, archaeologists have discovered that prehistoric Mississippians had a similar pattern of settlement. For example, the Moundville site was a large, fortified capital town containing many mounds that was surrounded by smaller, one-mound sites.

Moundville Diagram

Archaeologists believe that the Mississippian peoples were organized into chiefdoms, a form of political organization united under an official leader, or “chief.” Chiefdom societies were organized by families of differing social rank or status. Although people in chiefdoms inherited their rank at birth, they could gain prestige through personal achievement, as shown in the historical evidence. First, accounts of Mississippians in Alabama written by sixteenth-century Spanish explorers suggest chiefdoms were present at that time. These accounts mention powerful chiefs living in large capital towns marked by earthen mounds and protected by wooden palisades. Less powerful chiefs in smaller surrounding settlements paid tribute to their capital town. Second, archaeologists have discovered that prehistoric Mississippians had a similar pattern of settlement. For example, the Moundville site was a large, fortified capital town containing many mounds that was surrounded by smaller, one-mound sites.

Third, differences in burial location and grave goods reveal levels of social rank and inheritance. At Moundville in west-central Alabama, most people were buried in cemeteries near their houses; their graves contained a few common tools or nothing at all. Certain people, however, including some children, were buried in mounds and accompanied by rare copper and shell ornaments and fancy pottery. Because these children were too young to have earned their high status, they must have inherited it. A few mound burials contained adult skeletons buried with copper axes. Because the axes are purely symbolic (being too soft to function as tools) and are not found in other Moundville burials, archaeologists think these individuals were high-ranking chiefs. There were limits to power in these societies, however. High-ranking people were no healthier than common people. There is no evidence for a class of full-time artisans or merchants separate from food producers. The Mississippians lived in towns led by chiefs, not in cities ruled by kings and queens.

Burial mounds served as monuments to high-ranking families, but mounds were built for other purposes as well. Many mounds are flat-topped platforms of earth; most are less than 10 feet high, but some are larger. The largest known Mississippian mound, 100 feet high, is at the Cahokia site, located in Illinois just across the river from St. Louis, Missouri.

Excavations reveal that platform mounds were built in several construction stages over time. Typically, the tops of each stage contain remains of buildings that are larger than common houses. At the bases of some mounds, archaeologists recovered food garbage and broken pots cast down from the mound summits. These were likely the residences of leaders, who stored large quantities of food and hosted great feasts for their guests. The Moundville site, with 29 mounds arranged around an open plaza, is the largest Mississippian site in Alabama. Most mound sites, including Lubbub Creek, had only one mound.

Our knowledge of Mississippian religious and ceremonial life is limited. Weapons are prominent images on artifacts. Copper ornaments, shell pendants, and pottery vessels depict clubs, axes, arrows, severed heads, skulls, bones, and scalps. Some images show falcons, human-falcon beings, warriors, and monsters such as winged snakes. Some pottery vessels were made in the shape of animals such as frogs, fish, and birds, with pottery heads and tails serving as pot handles. Humans are also depicted, such as a mother-with-child theme or “head pots” depicting a dead person or spirit. The decorative arts served to represent ideas and values important to Mississippian peoples. Clearly, the Mississippians were concerned with such universal themes as life, death, fertility, ancestors, war, mythic beings, and heroes.

Decline of the Mississippian Tradition

Prehistory came to an end in Alabama when Mississippian peoples met the army of Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto in 1540. This and other encounters with Europeans introduced new diseases for which the long-isolated indigenous peoples had no resistance. Thousands died, bringing the Mississippian Tradition to an end. However, the Mississippian Tradition began to change before Europeans ever set foot on North America. The largest Mississippian sites were abandoned or in decline by 1450. Archaeologists do not know why so many of the largest sites were abandoned, but prolonged drought, crop failures, and warfare are possible causes.

Although archaeologists do not know what languages were spoken or what people called themselves at prehistoric archaeological sites, many Native Americans living in Alabama in historic times and today are the descendants of Mississippian peoples. The Choctaws, Creeks, and Cherokees of early historic times no longer built mounds, but they regarded the abandoned Mississippian mounds as symbols of the fertile earth and the origin places of their ancestors. Mississippian sites in Alabama include Moundville Archaeological Park, Fort Toulouse-Fort Jackson historical park near Wetumpka, and Bottle Creek National Historic Landmark in the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta near Stockton.

Further Reading

- Blitz, John H. Ancient Chiefdoms of the Tombigbee. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

- Milner, George R. The Moundbuilders: Ancient Peoples of Eastern North America. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2004.

- Walthall, John A. Prehistoric Indians of the Southeast: Archaeology in Alabama and the Middle South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1980.