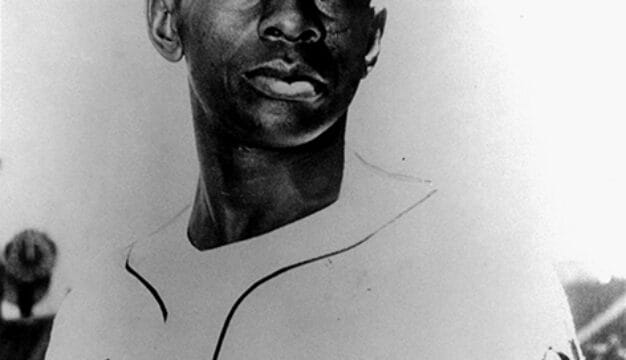

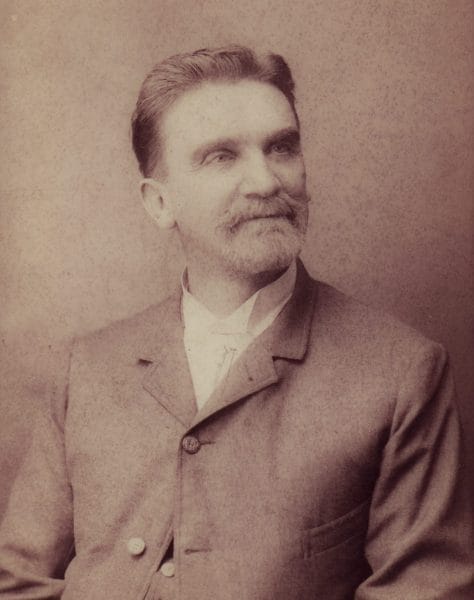

Peter Bryce

Peter Bryce

Peter Bryce (1834-92) was a pioneering figure in the field of mental health. Practicing in the post–Civil War era, he championed more humane therapeutic treatments for the mentally ill. He held important offices in both state and national organizations relating to the health professions and was the first superintendent of the state mental hospital that now bears his name.

Peter Bryce

Peter Bryce (1834-92) was a pioneering figure in the field of mental health. Practicing in the post–Civil War era, he championed more humane therapeutic treatments for the mentally ill. He held important offices in both state and national organizations relating to the health professions and was the first superintendent of the state mental hospital that now bears his name.

Bryce was born in Columbia, South Carolina, to Peter and Martha Smith Bryce. He graduated with distinction from The Citadel in 1855 and New York’s Medical College (now New York University School of Medicine) in 1859. After graduating, Bryce travelled in Europe, where his developing interest in mental health was enhanced during visits to psychiatric hospitals. Upon his return, he worked at psychiatric hospitals in New Jersey and South Carolina.

In late 1859, Dorothea Dix, a teacher and nationally renowned advocate for the mentally ill, brought Bryce to the attention of the trustees of the Alabama Insane Hospital (AIH). Located in Tuscaloosa, the institution had been created by the state legislature in 1852 but remained under construction for most of the decade. Despite his youth, Bryce’s training and southern roots were viewed favorably by the trustees, and in July 1860 they selected him to be the hospital’s first superintendent. Bryce accepted and moved to Tuscaloosa soon after marrying Ellen Clarkson, also of Columbia. The childless couple would devote all of their attention to AIH for the next 30 years. As construction was completed, Bryce developed the institutional policies and procedures by which the hospital was governed. As a public institution, AIH’s finances were constrained by perpetual state budget shortfalls, and the hospital was perennially underfunded.

Bryce Hospital

Like many of his contemporaries, Bryce believed that insanity was caused by the interplay of genetics and environmental and social factors, and that effective treatment should seek to filter out these factors and give the mind time to “heal.” This therapeutic approach, known as moral treatment (so called for its supposed ability to lead patients to an understanding and acceptance of “right” behavior) consisted of creating a normalized environment characterized by kind treatment, absence of physical restraints, and regular work by all patients who were able. It became popular after the Civil War as some hospitals reported extraordinary successes. Bryce continued to employ moral treatment even after learning of gross exaggerations at other psychiatric institutions in its success rates. Despite these overstatements of its effectiveness, Bryce was convinced that moral treatment was vastly superior to the forced idleness that characterized mental healthcare prior to the advent of moral treatment.

Bryce Hospital

Like many of his contemporaries, Bryce believed that insanity was caused by the interplay of genetics and environmental and social factors, and that effective treatment should seek to filter out these factors and give the mind time to “heal.” This therapeutic approach, known as moral treatment (so called for its supposed ability to lead patients to an understanding and acceptance of “right” behavior) consisted of creating a normalized environment characterized by kind treatment, absence of physical restraints, and regular work by all patients who were able. It became popular after the Civil War as some hospitals reported extraordinary successes. Bryce continued to employ moral treatment even after learning of gross exaggerations at other psychiatric institutions in its success rates. Despite these overstatements of its effectiveness, Bryce was convinced that moral treatment was vastly superior to the forced idleness that characterized mental healthcare prior to the advent of moral treatment.

Bryce extolled the therapeutic value of work—often arguing that idle hands allowed mental patients too much time to focus on their condition—and pragmatically recognized patient labor as essential to AIH’s economic survival in the face of diminishing state funds and a patient population that, over the period of his superintendence, averaged 85 percent indigents. Income derived from the patients’ vegetable garden and the manufacture of household goods became an important supplement to state support.

Bryce Hospital Laundry

The superintendent of AIH for 32 years, Bryce served in his position longer than most of his contemporaries and held several important offices in professional organizations. He was elected president of the predecessor to the American Psychiatric Association, and he became the focus of criticism by practitioners who favored restraint of patients. He also served as president of both the state medical and state historical associations in Alabama. Ironically, charges of abuse of patient labor by subsequent superintendents caused the hospital to become the focus of court decisions in the 1970s that led to outright release of many patients and removal of others to less restricted environments.

Bryce Hospital Laundry

The superintendent of AIH for 32 years, Bryce served in his position longer than most of his contemporaries and held several important offices in professional organizations. He was elected president of the predecessor to the American Psychiatric Association, and he became the focus of criticism by practitioners who favored restraint of patients. He also served as president of both the state medical and state historical associations in Alabama. Ironically, charges of abuse of patient labor by subsequent superintendents caused the hospital to become the focus of court decisions in the 1970s that led to outright release of many patients and removal of others to less restricted environments.

Bryce’s life was so intricately entwined with the AIH that at his death from Bright’s disease on August 14, 1892, he was buried on the hospital grounds, and AIH was later renamed Bryce Hospital.

Further Reading

- Weaver, Bill. “Establishing and Organizing the Alabama Insane Hospital, 1846-1861.” Alabama Review 47 (July 1995): 219–32.

- ———. “Survival at the Alabama Insane Hospital, 1861–1892.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 51 (January 1996): 5–28.