Moundville Archaeological Park

Aerial View of Moundville

Moundville Archaeological Park contains the remains of one of the largest prehistoric Native American settlements in the United States. It is located on the banks of the Black Warrior River, 14 miles south of Tuscaloosa, near the modern town of Moundville in Hale County. Once a thriving ceremonial and political center of Mississippian culture, the prehistoric Moundville site was occupied for more than three centuries until it was abandoned in the sixteenth century. The present-day park encompasses the original site, with its large earthen mounds arranged around an open plaza, the Jones Archaeological Museum with interpretive displays of artifacts, an archaeological research center, a nature trail, and camping facilities. Administered by the University of Alabama (UA) Museums, Moundville Archaeological Park receives about 40,000 visitors a year, including hundreds of Alabama school children.

Aerial View of Moundville

Moundville Archaeological Park contains the remains of one of the largest prehistoric Native American settlements in the United States. It is located on the banks of the Black Warrior River, 14 miles south of Tuscaloosa, near the modern town of Moundville in Hale County. Once a thriving ceremonial and political center of Mississippian culture, the prehistoric Moundville site was occupied for more than three centuries until it was abandoned in the sixteenth century. The present-day park encompasses the original site, with its large earthen mounds arranged around an open plaza, the Jones Archaeological Museum with interpretive displays of artifacts, an archaeological research center, a nature trail, and camping facilities. Administered by the University of Alabama (UA) Museums, Moundville Archaeological Park receives about 40,000 visitors a year, including hundreds of Alabama school children.

Moundville and Its Inhabitants

Because there are no written records from the Mississippian period, what is known about life at the Moundville site has been learned through archaeology. The Moundville site was founded around 1120 by Native American peoples of the Mississippian period, so named for its origins along the Mississippi River. The 185-acre site was a planned community. The huge plaza was artificially filled and leveled, and the 29 mounds were placed deliberately around it. Mounds were constructed by piling up basketloads of soil dug from nearby pits (now small lakes). Most of the mounds are flat-topped platforms and were built up over many decades in a series of construction stages. The mounds range from three to 57 feet high.

Nature Trail at Moundville

Archaeologists do not know why so many people came together to create the large town at the Moundville site. It is known that the Mississippian peoples of Moundville hunted, fished, and cultivated crops, especially corn. Around the time of Moundville’s initial construction, Mississippian farmers had intensified their corn production, and thus a food surplus was available to support large settled populations. The remains of fortifications indicate that warfare may also have been a factor. A log-walled palisade and earthwork was erected early in the site’s construction. By 1300, Moundville was the largest town in what is now Alabama. Given the number and density of house remains and human burials, archaeologists estimate that 1,000 people lived behind Moundville’s walls. Perhaps more lived in small family farmsteads scattered north and south of the main town along the Black Warrior River.

Nature Trail at Moundville

Archaeologists do not know why so many people came together to create the large town at the Moundville site. It is known that the Mississippian peoples of Moundville hunted, fished, and cultivated crops, especially corn. Around the time of Moundville’s initial construction, Mississippian farmers had intensified their corn production, and thus a food surplus was available to support large settled populations. The remains of fortifications indicate that warfare may also have been a factor. A log-walled palisade and earthwork was erected early in the site’s construction. By 1300, Moundville was the largest town in what is now Alabama. Given the number and density of house remains and human burials, archaeologists estimate that 1,000 people lived behind Moundville’s walls. Perhaps more lived in small family farmsteads scattered north and south of the main town along the Black Warrior River.

Social Structure

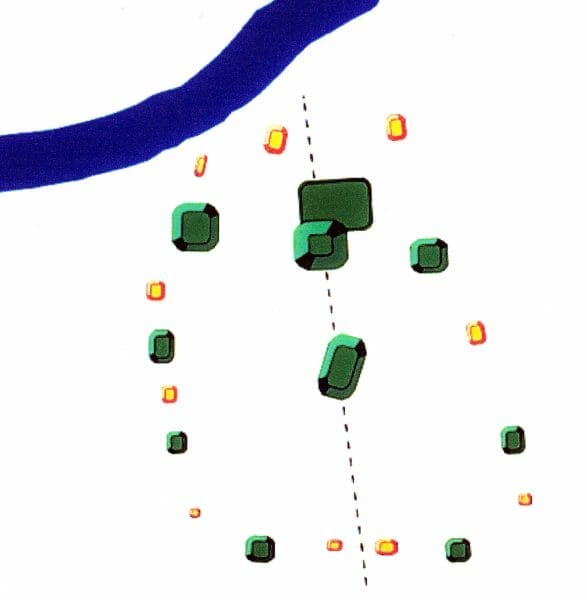

Moundville Diagram

The form, arrangement, and content of the mounds reveal the social structure at Moundville. Residential mounds alternate with burial mounds around the perimeter of the plaza. The largest residential mounds and those with the most elaborate burials are located along the northern boundary of the plaza. Mound A, a ceremonial structure of uncertain function, stands near the plaza’s center. Most of Moundville’s residents were buried in graves near their houses, and many of them were buried with simple goods such as common tools. Elites lived on the tops of the larger mounds and were buried with artifacts of stone, copper, and shell in the smaller mounds. The raw copper and shell were obtained from distant sources, and not everyone in Moundville society could make or acquire these rare items. Some artifacts appear to be items indicating wealth. Other objects appear to be symbols of rank or authority. Several adult skeletons found in the northernmost burial mounds were interred with copper axes found nowhere else on the site. The fact that the axes were made from copper, which made them too soft to function as tools or weapons, indicates that they were probably ceremonial and that these people likely had a leadership or chiefly status. Archaeologists thus surmise that ancient Moundville society was composed of at least three social categories: low-ranking workers and farmers, high-ranking elites, and the “chiefs” with ceremonial axes.

Moundville Diagram

The form, arrangement, and content of the mounds reveal the social structure at Moundville. Residential mounds alternate with burial mounds around the perimeter of the plaza. The largest residential mounds and those with the most elaborate burials are located along the northern boundary of the plaza. Mound A, a ceremonial structure of uncertain function, stands near the plaza’s center. Most of Moundville’s residents were buried in graves near their houses, and many of them were buried with simple goods such as common tools. Elites lived on the tops of the larger mounds and were buried with artifacts of stone, copper, and shell in the smaller mounds. The raw copper and shell were obtained from distant sources, and not everyone in Moundville society could make or acquire these rare items. Some artifacts appear to be items indicating wealth. Other objects appear to be symbols of rank or authority. Several adult skeletons found in the northernmost burial mounds were interred with copper axes found nowhere else on the site. The fact that the axes were made from copper, which made them too soft to function as tools or weapons, indicates that they were probably ceremonial and that these people likely had a leadership or chiefly status. Archaeologists thus surmise that ancient Moundville society was composed of at least three social categories: low-ranking workers and farmers, high-ranking elites, and the “chiefs” with ceremonial axes.

Between 1300 and 1450, the mounds gradually fell out of use, and most of Moundville’s inhabitants left the great town. Evidence suggests that they founded new single-mound sites nearby along the river. No longer a town, the Moundville site became primarily a place where people were buried. The pottery vessels and ornaments of stone, copper, and shell found in burials from this period were decorated with symbols such as a cross in a circle, a hand and eye, a forked eye, falcons, and winged and horned serpents, skulls and bones, scalps, and arrows. These symbols are thought to represent Moundville’s reinvention as a place of funeral ceremonies and a focus for such themes as ancestors, war, and death.

Archaeologists have not determined precisely when and why Moundville was abandoned. By 1540, when explorer Hernando de Soto marched his army of Spanish conquistadors through the area, Moundville likely had few inhabitants. None of the villages described in accounts of the expedition can be identified with certainty as Moundville, and subsequent written descriptions of the area do not appear again until the early eighteenth century, when the region was found to be mostly uninhabited. This gap in the written record has made it difficult to link Moundville’s inhabitants with historically known Native American groups.

Excavating Moundville

Reconstructed Mississippian Compound

Little attention was paid to the Moundville site until 1869, when Nathaniel T. Lupton, fifth president of the UA, mapped the site. Early in the twentieth century, private collector Clarence B. Moore conducted several excavations into the mounds and unearthed dozens of attractive pottery vessels, stone pipes, axes, and palettes (disk-shaped objects covered with paint pigments), and copper and shell ornaments. Moore, a wealthy Philadelphian, travelled the South in his steamboat The Gopher, collecting ancient artifacts and publishing picture books of his finds. Alarmed at the extent of Moore’s digging and the fact that he sent the artifacts back to Philadelphia, the state of Alabama passed an antiquities law in 1915 to protect archaeological sites from looting. In the 1920s, several local citizens and state geologist Walter B. Jones led efforts to turn the site into a park. Jones mortgaged his house to fund the purchase of the site, and Mound State Park (later renamed Mound State Monument) was established in 1933.

Reconstructed Mississippian Compound

Little attention was paid to the Moundville site until 1869, when Nathaniel T. Lupton, fifth president of the UA, mapped the site. Early in the twentieth century, private collector Clarence B. Moore conducted several excavations into the mounds and unearthed dozens of attractive pottery vessels, stone pipes, axes, and palettes (disk-shaped objects covered with paint pigments), and copper and shell ornaments. Moore, a wealthy Philadelphian, travelled the South in his steamboat The Gopher, collecting ancient artifacts and publishing picture books of his finds. Alarmed at the extent of Moore’s digging and the fact that he sent the artifacts back to Philadelphia, the state of Alabama passed an antiquities law in 1915 to protect archaeological sites from looting. In the 1920s, several local citizens and state geologist Walter B. Jones led efforts to turn the site into a park. Jones mortgaged his house to fund the purchase of the site, and Mound State Park (later renamed Mound State Monument) was established in 1933.

Jones Archaeological Museum

Jones, assisted by David L. DeJarnette, began the first scientific excavations at the park in 1929. From 1933 to 1941, at the height of the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) restored the mounds, built roads, and constructed a museum. Jones, DeJarnette, and others at the Alabama Museum of Natural History directed the force, excavating 500,000 square feet of the site, and more than 2,000 burials, 75 house remains, and thousands of artifacts. DeJarnette became director of the park in the 1950s, was a founding member of the UA Department of Anthropology, and was the leading archaeologist in the state for two decades. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, Indiana University professor Christopher S. Peebles and his students analyzed the enormous Depression-era collections of artifacts and human remains. UA’s Vernon J. Knight Jr., a student of DeJarnette’s, excavated several of the mounds in the 1990s. These efforts provided new insights into Moundville’s history and society. Much remains to be learned about the Moundville site and the people who built it. Only 14 percent of the site has been excavated. The development, sociopolitical organization, and eventual abandonment of ancient Moundville remain poorly understood. Every fall, a Native American festival is held at the park. Moundville Archaeological Park was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964.

Jones Archaeological Museum

Jones, assisted by David L. DeJarnette, began the first scientific excavations at the park in 1929. From 1933 to 1941, at the height of the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) restored the mounds, built roads, and constructed a museum. Jones, DeJarnette, and others at the Alabama Museum of Natural History directed the force, excavating 500,000 square feet of the site, and more than 2,000 burials, 75 house remains, and thousands of artifacts. DeJarnette became director of the park in the 1950s, was a founding member of the UA Department of Anthropology, and was the leading archaeologist in the state for two decades. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, Indiana University professor Christopher S. Peebles and his students analyzed the enormous Depression-era collections of artifacts and human remains. UA’s Vernon J. Knight Jr., a student of DeJarnette’s, excavated several of the mounds in the 1990s. These efforts provided new insights into Moundville’s history and society. Much remains to be learned about the Moundville site and the people who built it. Only 14 percent of the site has been excavated. The development, sociopolitical organization, and eventual abandonment of ancient Moundville remain poorly understood. Every fall, a Native American festival is held at the park. Moundville Archaeological Park was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964.

A $5 million renovation of the Jones Archaeological Museum at Moundville was completed in 2010, with the museum reopening in May of that year. The original museum’s 1939 Art Deco-style facade was retained, but the rear of the building was expanded to provide space for a museum shop, food court, and outside viewing platform. With funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the out-of-date interior was been transformed into an award-winning exhibition space now called “Lost Realm of the Black Warrior.” Initial planning for the renovation began in the early 1990s and was overseen by a team of archaeologists, folklorists, artists, exhibitors, and Native American consultants. The emphasis in all of the exhibits is on story-telling, which makes the educational and intellectual content accessible to visitors of all ages and backgrounds. The layout of the exhibit moves the visitor through a series of scene-setting experiences, each with full-sized human figures created from life-casts of contemporary Native American models; they include a wedding ceremony, a chief’s house, and a medicine maker telling stories in an earth lodge. The costumes were made by Native American and other artists using authentic materials and techniques. In addition to the scenes, rarely seen ancient artifacts unearthed at Moundville, such as the famous bird-serpent bowl carved from a single piece of stone and the rattlesnake disk, are also on display. More than two hundred artifacts are arranged at different eye levels and are easily viewed at close range. Murals depicting daily life adorn the walls of the exhibit space. The purpose of the new thematic structure is to immerse visitors in the culture of Moundville’s inhabitants and thereby humanize the past.

Further Reading

- Blitz, John H. Moundville. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

- Knight, Vernon James, Jr., and Vincas P. Steponaitis. “A New History of Moundville.” In The Archaeology of the Moundville Chiefdom, edited by Vernon James Knight Jr. and Vincas P. Steponaitis. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

- Moore, Clarence B. The Moundville Expeditions of Clarence Bloomfield Moore. Edited by Vernon James Knight Jr. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1996.

- Walthall, John A. Moundville: An Introduction to the Archaeology of a Mississippian Chiefdom. University of Alabama: The Alabama Museum of Natural History, 1977.