Tuskegee Boycott

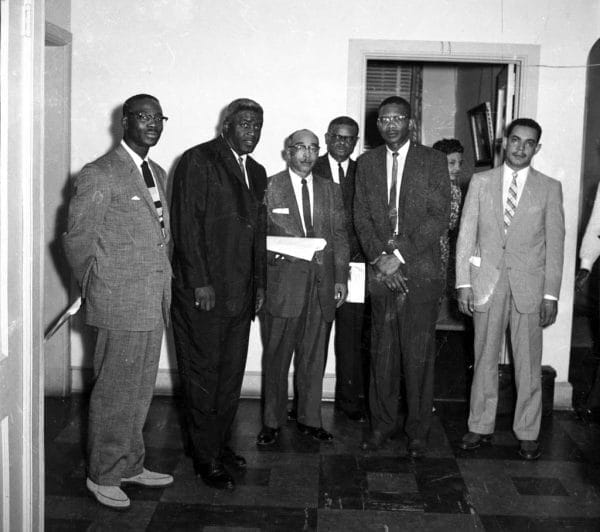

Tuskegee Civic Association and Jackie Robinson

In June 1957, African American residents of Macon County joined a selective buying campaign known as the Tuskegee Boycott to protest Local Act 140, state legislation that redrew Tuskegee boundaries to deprive the city’s eligible blacks of their right to vote in city elections. For more than three and half years, black protestors led by the Tuskegee Civic Association (TCA) refused to shop at white-operated Tuskegee businesses, forcing bankruptcies and closures and focusing national attention on Alabama’s denial of black voting rights. In response, the legislature considered dissolving Macon County and dividing its land among neighboring counties, but such legislature was never enacted. Ultimately, the 1960 landmark Supreme Court voting rights case Gomillion v. Lightfoot overturned Local Act 140 and restored the city’s previous boundaries.

Tuskegee Civic Association and Jackie Robinson

In June 1957, African American residents of Macon County joined a selective buying campaign known as the Tuskegee Boycott to protest Local Act 140, state legislation that redrew Tuskegee boundaries to deprive the city’s eligible blacks of their right to vote in city elections. For more than three and half years, black protestors led by the Tuskegee Civic Association (TCA) refused to shop at white-operated Tuskegee businesses, forcing bankruptcies and closures and focusing national attention on Alabama’s denial of black voting rights. In response, the legislature considered dissolving Macon County and dividing its land among neighboring counties, but such legislature was never enacted. Ultimately, the 1960 landmark Supreme Court voting rights case Gomillion v. Lightfoot overturned Local Act 140 and restored the city’s previous boundaries.

At the time of the boycott, blacks outnumbered whites four to one in Tuskegee and also outnumbered whites in Macon County’s rural areas. This demographic reflected how, prior to emancipation, the number of Alabama’s enslaved persons had steadily increased to comprise nearly half the state’s population. Despite Tuskegee’s black majority, whites controlled the city government, the school board, and law enforcement and commerce, such as stores, banks, and car dealerships. City residents of both races still adhered to Booker T. Washington‘s ideas about the races cooperating yet remaining segregated and his belief in “polite” social interactions across racial lines. Because of white supremacy, blacks were expected to always be respectful to whites, who erroneously assumed that polite blacks were content, despite having no representation in local government. In reality, blacks wanted to be treated as full citizens who could freely exercise the right to vote, and a number of factors had prompted an increase in black voter registrations in the years prior to the boycott.

Formally established in 1941, the TCA had long been promoting voting rights. The TCA encouraged members to engage in civic activism and to register to vote, despite intimidation through violence and suppression tactics such as the poll tax and unfair literacy tests. TCA voter registration clinics educated blacks on how to register to vote and facilitated a steady increase in registered black voters each year. In addition, the aftermath of World War II prompted increasing numbers of southern blacks, emboldened by the black soldiers who fought valiantly during the war, to became registered voters. Aspiring black voters were also encouraged by sweeping civil rights victories, particularly the 1954 landmark school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Act of 1957. It established the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, empowered to investigate civil rights violations, and a civil rights division within the U.S. Department of Justice that would take legal action against violators.

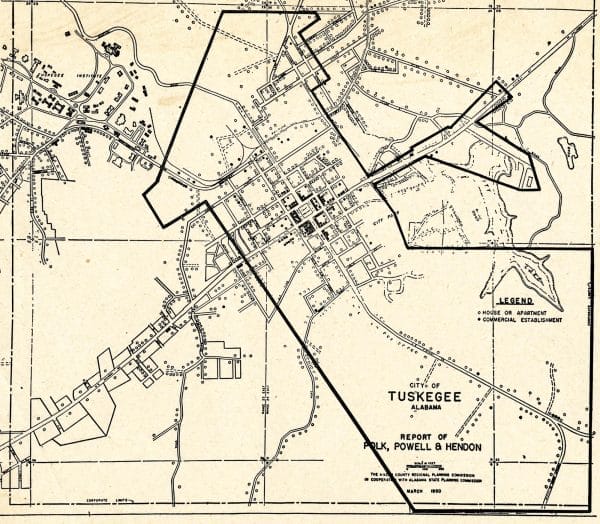

Tuskegee Redistricting Map

The growing black electorate in Tuskegee fueled anxiety among whites, however, who feared that black citizens would gain the upper hand in politics. In May 1957, state senator Samuel M. Engelhardt introduced Senate Bill 291 to change Tuskegee boundaries from a square to a 28-sided configuration that oddly resembled a seahorse. Engelhardt, an influential Macon County resident and member of the pro-segregation Alabama Association of White Citizen’s Councils, was a long-time advocate for white supremacy and opponent of black suffrage. His legislation aimed to place approximately 3,500 0f 5,000 black city residents and 400 of the city’s 410 registered black voters and even Tuskegee Institute outside city boundaries but retain more than 1,300 white residents inside to achieve a majority of nearly 600 white city registered voters.

Tuskegee Redistricting Map

The growing black electorate in Tuskegee fueled anxiety among whites, however, who feared that black citizens would gain the upper hand in politics. In May 1957, state senator Samuel M. Engelhardt introduced Senate Bill 291 to change Tuskegee boundaries from a square to a 28-sided configuration that oddly resembled a seahorse. Engelhardt, an influential Macon County resident and member of the pro-segregation Alabama Association of White Citizen’s Councils, was a long-time advocate for white supremacy and opponent of black suffrage. His legislation aimed to place approximately 3,500 0f 5,000 black city residents and 400 of the city’s 410 registered black voters and even Tuskegee Institute outside city boundaries but retain more than 1,300 white residents inside to achieve a majority of nearly 600 white city registered voters.

True to its history of disenfranchising blacks through legislation, most notably the Alabama Constitution of 1901, the Alabama House and Senate both unanimously passed the Engelhardt bill, and it was enacted without Gov. James “Big Jim” Folsom‘s signature as Local Act 140. Although news articles about Act 140 appeared frequently during May and June in local and regional papers, the city’s white merchants claimed to be caught by surprise by the legislation and did not collectively denounce the gerrymander or offer support to black voters.

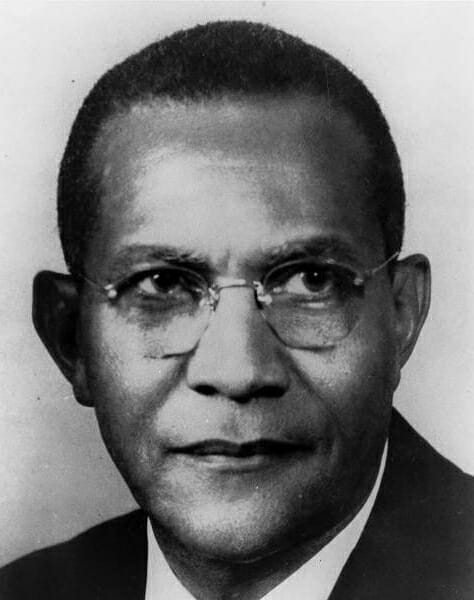

Charles Gomillion

Led by Tuskegee Institute sociology professor and dean of students, TCA president Charles G. Gomillion (1900-1995) and its members swiftly organized a protest, outraged by the legislature’s actions and the white merchants’ dubious claim of ignorance. Gomillion presided over the TCA’s first public protest meeting at the Butler Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church on June 25, 1957. Newspaper reports indicate that thousands of black Macon County residents filled the church until the crowd overflowed to the outdoors. The people sang hymns, prayed, and listened as Gomillion presented the plan to launch a voluntary selective buying campaign. Gomillion urged the crowd to unite under the motto “Trade with Your Friends.” TCA secretary William P. Mitchell also spoke on behalf of protestors, explaining that if blacks were not welcome to reside in Tuskegee, they would not shop in Tuskegee either.

Charles Gomillion

Led by Tuskegee Institute sociology professor and dean of students, TCA president Charles G. Gomillion (1900-1995) and its members swiftly organized a protest, outraged by the legislature’s actions and the white merchants’ dubious claim of ignorance. Gomillion presided over the TCA’s first public protest meeting at the Butler Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church on June 25, 1957. Newspaper reports indicate that thousands of black Macon County residents filled the church until the crowd overflowed to the outdoors. The people sang hymns, prayed, and listened as Gomillion presented the plan to launch a voluntary selective buying campaign. Gomillion urged the crowd to unite under the motto “Trade with Your Friends.” TCA secretary William P. Mitchell also spoke on behalf of protestors, explaining that if blacks were not welcome to reside in Tuskegee, they would not shop in Tuskegee either.

At the outset, TCA officials could not predict whether the selective buying campaign would be effective. Gomillion explained repeatedly that people could decide for themselves to participate or not. Black sharecroppers and tenant farmers who had little cash continued to shop with the white merchants who sold to them on credit and profited most from sales to the majority black population. Some rural residents were apathetic about voting and refrained from boycotting. Additionally, long-standing social class differences between Tuskegee’s middle-class professionals, many of whom worked at Tuskegee and the nearby Veterans Hospital and in the public school system, and the rural working-class posed a barrier to county-wide black participation. Eventually, Tuskegee’s black middle-class surmised that racial discrimination placed them in the same predicament as rural blacks. When a rumor circulated among black rural residents that a white merchant boasted to a newspaper reporter that the rural blacks still shopped at his store, it prompted a number of rural residents to prove him wrong by joining the campaign. Ultimately middle- and working-class blacks acknowledged a common cause to preserve black voting rights. This shared understanding enabled them to work together to form carpools and shopping co-ops to ensure that boycotters could obtain needed food, clothing, and supplies. The united effort increased TCA membership rolls, eased the strain on boycotters, and caused 26 white-operated businesses to close within two years.

Engelhardt reacted to the unified boycott and widespread sympathetic news coverage by doubling-down on his effort to eliminate Tuskegee’s black majority. In early July 1957, he introduced legislation to dissolve Macon County entirely, proposing boundary changes that would have divided Macon County into sections to be absorbed by Bullock, Elmore, Lee, Montgomery, and Tallapoosa Counties. The legislature put the proposal on the ballot and Alabamians voted in favor of the proposal; Alabama Constitutional Amendment 132 was ratified. The Amendment gave the legislature authority to convene a committee at any time it saw fit to initiate proceedings to abolish Macon County, but it was later repealed by Amendment 406.

In late July 1957, Alabama Attorney General John Patterson initiated two surprise raids on TCA headquarters to determine if the TCA was violating Alabama’s antiboycott law. The law made it illegal to force people to participate in a boycott and had been used in 1956 to charge Martin Luther King Jr. and other Montgomery Bus Boycott leaders with a crime. Patterson personally oversaw one of the raids, convinced that the TCA was a subversive organization intent on destroying the government. He also issued an injunction alleging that the TCA was conducting an illegal boycott and ordered them to stop. Prominent civil rights attorneys Fred D. Gray and Arthur Shores defended the TCA at a January 1958 trial in which Judge Will O. Walton ruled that the state failed to prove its case, dismissing the injunction.

Martin Luther King Jr. in Tuskegee

The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith (ADL) offered support in numerous ways to bolster the spirits of the boycotters. MIA leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph D. Abernathy delivered stirring speeches in 1957 at Tuskegee’s Washington Chapel AME Church, adding to the tradition of faith-based massive resistance to racial injustice. The meeting was one of many TCA-led mass meetings held regularly throughout the boycott to encourage perseverance. Likewise, in 1958, Ella Baker, associate director of SCLC’s Crusade for Citizenship, asked the TCA to send a delegate to its mass meeting in Atlanta to report on voting rights discrimination as it aimed to double the number of black voters in the South. Baker intended for the TCA delegate’s report to represent the status of black voter discrimination in the South to the Civil Rights Commission. In 1959, the ADL, an organization dedicated to securing justice and fair treatment for Jewish people, blacks, and other oppressed groups, published the book Voting Rights and Economic Pressure, which presented the selective buying campaign as a model for voting rights activism.

Martin Luther King Jr. in Tuskegee

The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith (ADL) offered support in numerous ways to bolster the spirits of the boycotters. MIA leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph D. Abernathy delivered stirring speeches in 1957 at Tuskegee’s Washington Chapel AME Church, adding to the tradition of faith-based massive resistance to racial injustice. The meeting was one of many TCA-led mass meetings held regularly throughout the boycott to encourage perseverance. Likewise, in 1958, Ella Baker, associate director of SCLC’s Crusade for Citizenship, asked the TCA to send a delegate to its mass meeting in Atlanta to report on voting rights discrimination as it aimed to double the number of black voters in the South. Baker intended for the TCA delegate’s report to represent the status of black voter discrimination in the South to the Civil Rights Commission. In 1959, the ADL, an organization dedicated to securing justice and fair treatment for Jewish people, blacks, and other oppressed groups, published the book Voting Rights and Economic Pressure, which presented the selective buying campaign as a model for voting rights activism.

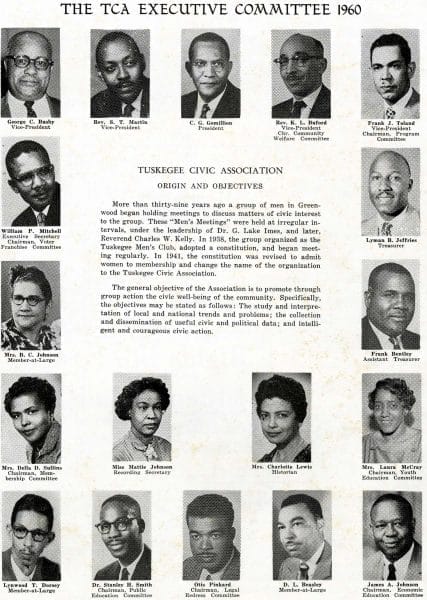

Tuskegee Civic Association Flyer

The TCA made a crucial legal move in August 1958 when 11 black plaintiffs and Gomillion filed suit against Tuskegee mayor Phillip M. Lightfoot and other local government officials. The lawsuit charged that Act 140 and its enforcers with violating the Fourteenth Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court heard the case, Gomillion v. Lightfoot, in October 1960 and ruled in November 1960 that the Act violated the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibits jurisdictions from changing voting district boundaries to deny African Americans equal political representation. The breakthrough ruling precipitated the Tuskegee boycott’s end in February 1961. Although the boycott succeeded in restoring Tuskegee’s black electorate and in bolstering numerous black-owned businesses, the city suffered economically as a result of white backlash in the form of out-migration and diminished economic investment. Other factors also challenged economic growth: the overall population declined, hindering the city’s ability to attract large-scale industrial and service-sector jobs to replace agricultural jobs that had been declining since the 1940s owing to farm mechanization.

Tuskegee Civic Association Flyer

The TCA made a crucial legal move in August 1958 when 11 black plaintiffs and Gomillion filed suit against Tuskegee mayor Phillip M. Lightfoot and other local government officials. The lawsuit charged that Act 140 and its enforcers with violating the Fourteenth Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court heard the case, Gomillion v. Lightfoot, in October 1960 and ruled in November 1960 that the Act violated the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibits jurisdictions from changing voting district boundaries to deny African Americans equal political representation. The breakthrough ruling precipitated the Tuskegee boycott’s end in February 1961. Although the boycott succeeded in restoring Tuskegee’s black electorate and in bolstering numerous black-owned businesses, the city suffered economically as a result of white backlash in the form of out-migration and diminished economic investment. Other factors also challenged economic growth: the overall population declined, hindering the city’s ability to attract large-scale industrial and service-sector jobs to replace agricultural jobs that had been declining since the 1940s owing to farm mechanization.

Participants in the Tuskegee boycott engaged in unwavering civil activism to end the expulsion of black city residents and re-establish their voting rights. Like their counterparts in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, black residents of Macon County forged a model of sustained mass resistance that other activists, black and white, subsequently adopted to push for passage of the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Further Reading

- Gomillion, C. G. “The Tuskegee Voting Story.” Clinical Sociology Review 6(1): 22-26 (1988).

- Guzman, Jessie Parkhurst. Crusade for Civic Democracy: The Story of the Tuskegee Civic Association, 1941-1970. New York: Vantage Press, 1984.

- Norrell, Robert J. Reaping the Whirlwind: The Civil Rights Movement in Tuskegee. New York: Vintage Books, 1985.

- Taper, Bernard. Gomillion Versus Lightfoot: The Tuskegee Gerrymander Case. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1962.