Fort Condé

Fort Condé

Fort Condé was constructed by the French in 1723 in the French city of Mobile during the colonial period. The fort, built of locally made brick, stone, earthen walls, and cedar, covered more than 10 acres of land and would have encompassed much of present-day downtown Mobile. The structure was named in honor of Louis Henri de Bourbon, Duke of Bourbon, Prince of Condé. He was named prime minister by the French king, Louis XV, the year construction began. Until its destruction in 1823, the fort was occupied consecutively by France, Great Britain, Spain, and the United States. It was the center of society, the seat of government, and a defense against hostile neighbors and the threat of conquest. In 1976, the city of Mobile opened a replica of Fort Condé in recognition of its importance in Mobile’s long history. The fort now serves as a tourist attraction operated by the History Museum of Mobile.

Fort Condé

Fort Condé was constructed by the French in 1723 in the French city of Mobile during the colonial period. The fort, built of locally made brick, stone, earthen walls, and cedar, covered more than 10 acres of land and would have encompassed much of present-day downtown Mobile. The structure was named in honor of Louis Henri de Bourbon, Duke of Bourbon, Prince of Condé. He was named prime minister by the French king, Louis XV, the year construction began. Until its destruction in 1823, the fort was occupied consecutively by France, Great Britain, Spain, and the United States. It was the center of society, the seat of government, and a defense against hostile neighbors and the threat of conquest. In 1976, the city of Mobile opened a replica of Fort Condé in recognition of its importance in Mobile’s long history. The fort now serves as a tourist attraction operated by the History Museum of Mobile.

Colonial History

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville

In 1711, numerous problems at the original site of the French settlement of Mobile at Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff prompted its leaders, the Le Moyne brothers, to convince settlers to relocate more than 25 miles south along the Mobile River to the present site of Mobile. The residents of new Mobile, and members of nearby allied tribes, built a small wooden fort, called Fort Louis De La Louisiane after the fort at the original settlement. (A historic marker was placed nearby in 1971 east of Le Moyne.) By the 1720s, the fort had fallen into disrepair, and the French made plans to replace it with a new brick fort to serve as a symbol of their dominance in the area.

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville

In 1711, numerous problems at the original site of the French settlement of Mobile at Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff prompted its leaders, the Le Moyne brothers, to convince settlers to relocate more than 25 miles south along the Mobile River to the present site of Mobile. The residents of new Mobile, and members of nearby allied tribes, built a small wooden fort, called Fort Louis De La Louisiane after the fort at the original settlement. (A historic marker was placed nearby in 1971 east of Le Moyne.) By the 1720s, the fort had fallen into disrepair, and the French made plans to replace it with a new brick fort to serve as a symbol of their dominance in the area.

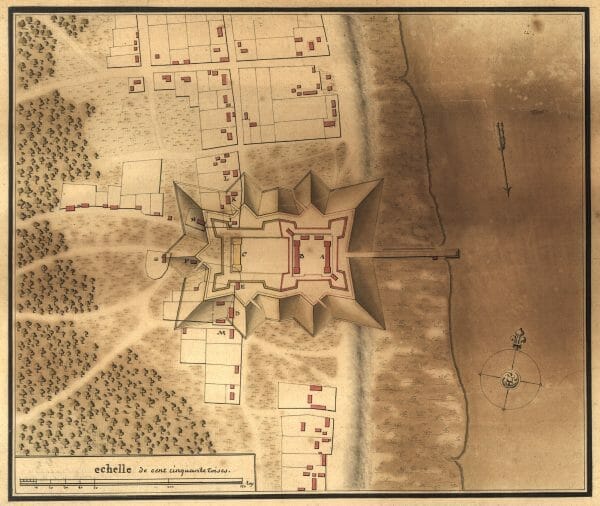

In 1723, construction began on the fort, which followed the designs of noted French military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, who died in 1707. French engineer Valentin Devin was tasked with supervising the construction of the large, 10- to 11-acre structure. Most of the workers who built the fort were enslaved men who had been brought to Mobile from villages in West Africa. According to contemporary illustrations, the fort was laid out in the shape of a four-pointed star with sloped masonry walls known as bastions that measured 300 to 360 feet from tip to tip and bore sentry towers. These walls were 16 to 20 feet tall and topped by a parapet four and a half feet high. (Sources vary as to the exact dimensions.) The fort’s cannons were placed behind this wall. The brick structure sat atop a seven-sided sloped earthwork known as a glacis, and the structure was surrounded by a moat, discovered during excavations in the latter 1960s. The east side, facing the river, featured a passage to a dock on the river. Alongside the interior area of the fort that surrounded the parade ground were three wells, a bake house, two long barracks that housed 216 men, and a magazine to store arms and gun powder. A planned chapel was never erected.

Fort Condé, 1743

In 1763, France lost its colonial possessions in North America with its defeat by Great Britain in the Seven Years’ War (known as the French and Indian War in North America). Fort Condé then became part of British West Florida, which at the time stretched from present-day Apalachicola, Florida, to the Mississippi River. The fort was renamed Fort Charlotte in honor of the wife of King George III. The British held the fort until March 1780, when Don Bernardo de Gálvez, the Spanish governor of Louisiana, and José Manuel de Ezpeleta led more than a 1,000 troops to Mobile and took control of Fort Charlotte from British commander Elias Durnford after a 14-day siege known as the Battle of Fort Charlotte. From 1780 to 1813, Spain ruled Mobile and the fort was renamed Fuerta Carlota, the Spanish pronunciation of Fort Charlotte. The Spanish refurbished the fort, and it continued to be an important center for trade.

Fort Condé, 1743

In 1763, France lost its colonial possessions in North America with its defeat by Great Britain in the Seven Years’ War (known as the French and Indian War in North America). Fort Condé then became part of British West Florida, which at the time stretched from present-day Apalachicola, Florida, to the Mississippi River. The fort was renamed Fort Charlotte in honor of the wife of King George III. The British held the fort until March 1780, when Don Bernardo de Gálvez, the Spanish governor of Louisiana, and José Manuel de Ezpeleta led more than a 1,000 troops to Mobile and took control of Fort Charlotte from British commander Elias Durnford after a 14-day siege known as the Battle of Fort Charlotte. From 1780 to 1813, Spain ruled Mobile and the fort was renamed Fuerta Carlota, the Spanish pronunciation of Fort Charlotte. The Spanish refurbished the fort, and it continued to be an important center for trade.

Early American Period

Fort Condé Re-enactors

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, which ended in 1783, relations between the Spanish and the newly established United States were tense. The United States coveted Mobile and its rich river system, and in April 1813, U.S. Army general James Wilkinson arrived with more than 1,000 men with orders from Pres. James Madison to take possession of the city. Unable to defend their position, the Spanish surrendered Fuerta Carlota without firing a shot on April 13. The United States took possession of Mobile and resurrected the name Fort Charlotte for the installation.

Fort Condé Re-enactors

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, which ended in 1783, relations between the Spanish and the newly established United States were tense. The United States coveted Mobile and its rich river system, and in April 1813, U.S. Army general James Wilkinson arrived with more than 1,000 men with orders from Pres. James Madison to take possession of the city. Unable to defend their position, the Spanish surrendered Fuerta Carlota without firing a shot on April 13. The United States took possession of Mobile and resurrected the name Fort Charlotte for the installation.

Mobile expanded rapidly in the ensuing years, and city officials began to call for the fort’s demolition so that the land could be used for other purposes. In 1818, the U.S. Congress authorized its sale to developers and demolition as it was no longer needed for defense. By 1823, nothing remained. The debris was used to fill in the marshy shoreline that occupied the area now under Water Street. The empty space where the fort once stood soon became home to a courthouse, Mobile’s first theater, and new homes and commercial buildings.

Reclaiming Fort Condé

Fort Condé Excavation Exhibit

In 1966, construction began on the George Wallace Tunnel under the Mobile River to facilitate the flow of traffic along Interstate 10. Because construction would disturb the original site of Fort Condé, the city contracted with archaeologists from the University of Alabama to remove all historic artifacts from the construction zone. Federal funds financed the majority of this three-year endeavor. Beginning in 1967, the dig uncovered thousands of eighteenth and early nineteenth century artifacts, including a part of Fort Condé’s original wall.

Fort Condé Excavation Exhibit

In 1966, construction began on the George Wallace Tunnel under the Mobile River to facilitate the flow of traffic along Interstate 10. Because construction would disturb the original site of Fort Condé, the city contracted with archaeologists from the University of Alabama to remove all historic artifacts from the construction zone. Federal funds financed the majority of this three-year endeavor. Beginning in 1967, the dig uncovered thousands of eighteenth and early nineteenth century artifacts, including a part of Fort Condé’s original wall.

Following the archaeological project, the Mobile Historic Development Commission recommended constructing a much smaller replica of the fort atop a portion of the original location. The city and a savings and loan association funded the construction of the fort, partially in recognition of the growing desire for tourism and historic development in a declining downtown. The effort involved the restoration and revitalization of several blocks of the Church Street East Historic District near the fort; a replica approximately one-third the size of the original and built on a four-fifths scale.

The fort was dedicated on July 11, 1976, as part of Mobile’s celebration of the U.S. Bicentennial. An estimated 3,000 people attended the opening ceremony, and guides in period attire offered tours of the fort. The newly opened fort became a department of the city of Mobile and featured a gift shop operated by the Mobile Convention and Visitors Bureau, which used the fort as the city’s official welcome center, one of the most unusual in the nation. In 2001, the then-Museum of Mobile, located across the street, gained control of Fort Condé and began making repairs to the building’s infrastructure. In 2009, the museum began a major renovation of the property using funds from existing contracts. In October 2013, the renovated Fort Condé reopened as the Fort of Colonial Mobile.

Fort Condé Iberville Exhibit

Interactive exhibits in multiple rooms enable visitors to learn about the people who colonized early Mobile. The rooms exhibit historic artifacts of Native Americans and Europeans who played important roles in the evolution of the city in a time shaped by innovation, conquest, plunder, piracy, and war. Many of the artifacts recovered during excavations of the original fort are part of the exhibit, notably from a well in which refuse was dumped and later excavated, including many, many pieces of glassware and ceramics. The museum features a barracks room of a typical French enlisted man, a jail cell, and cannon, muskets, and ammunition in the replica magazine. Another room showcases tools that would have been used by the fort’s inhabitants. On special occasions, re-enactors in period uniforms demonstrate some typical activities, including firing cannon and muskets. The open-air upper level of the fort, the parapet level, offers a panoramic view of the Mobile waterfront and features sentry posts and several cannon pointing through openings known as crenellations. Outside the fort are cannon that date from the French occupation.

Fort Condé Iberville Exhibit

Interactive exhibits in multiple rooms enable visitors to learn about the people who colonized early Mobile. The rooms exhibit historic artifacts of Native Americans and Europeans who played important roles in the evolution of the city in a time shaped by innovation, conquest, plunder, piracy, and war. Many of the artifacts recovered during excavations of the original fort are part of the exhibit, notably from a well in which refuse was dumped and later excavated, including many, many pieces of glassware and ceramics. The museum features a barracks room of a typical French enlisted man, a jail cell, and cannon, muskets, and ammunition in the replica magazine. Another room showcases tools that would have been used by the fort’s inhabitants. On special occasions, re-enactors in period uniforms demonstrate some typical activities, including firing cannon and muskets. The open-air upper level of the fort, the parapet level, offers a panoramic view of the Mobile waterfront and features sentry posts and several cannon pointing through openings known as crenellations. Outside the fort are cannon that date from the French occupation.

The museum available to rent and is open year round and charges an admission fee. It has a gift shop that features period-themed items.

Further Reading

- Delaney, Caldwell. The Story of Mobile. Mobile: The Haunted Book Shop, 1981.

- Hamilton, Peter J. Colonial Mobile. 1910. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

- Thomason, Michael V. R., ed. Mobile: The New History of Alabama’s First City. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.