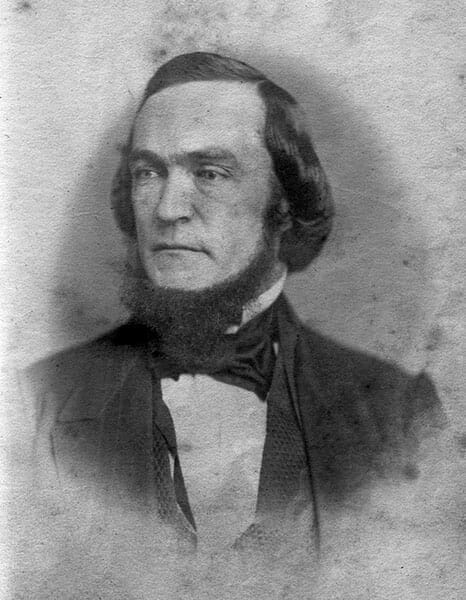

Eli Sims Shorter

Eli Sims Shorter

Eli Sims Shorter (1823-1879) represented Alabama‘s Second Congressional District for two consecutive terms from 1855 to 1859. The Democrats in his district were attracted to Shorter’s eloquent speeches and supported his stance that favored southern states’ rights. At the end of his second term, he retired from Congress, preferring to pursue private business matters over politics. He later served as a colonel in the Confederate Army in the western theater of the American Civil War.

Eli Sims Shorter

Eli Sims Shorter (1823-1879) represented Alabama‘s Second Congressional District for two consecutive terms from 1855 to 1859. The Democrats in his district were attracted to Shorter’s eloquent speeches and supported his stance that favored southern states’ rights. At the end of his second term, he retired from Congress, preferring to pursue private business matters over politics. He later served as a colonel in the Confederate Army in the western theater of the American Civil War.

Shorter was born in Monticello, Georgia, on March 15, 1823, to Reuben Clark Shorter, a physician, and Mary Butler Gill Shorter; he had 11 brothers and sisters. Reuben, who was from Culpepper County, Virginia, was abandoned at a young age but accumulated enough money during his adolescence to pay for his education, including a medical degree from the Medical University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Eli attended the common schools in the Jasper County area before his family relocated in the fall of 1837 to Irwinton, (present-day Eufaula) Barbour County. Reuben founded the Baptist Church in Eufaula, and Eli’s brother, John Gill Shorter, would serve as Alabama governor (1861-63) during the first years of the Civil War.

Eli began his college studies at Franklin College (present-day University of Georgia) and then enrolled at Yale College (present-day Yale University) in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1839. He graduated in 1843 and delivered the salutary oration to his graduating class during commencement. Eli then enrolled in Yale Law School, where he graduated with a law degree one year later. He returned to Eufaula in 1844, was admitted to the Alabama State Bar, and opened a law practice with his brother John that became one of the most successful in the state. Eli married Marietta Fannin of Troup County, Georgia, on January 12, 1848. Marietta was the niece (although some sources say daughter) of Col. James Fannin, who gained fame during the Texas Revolution. The couple had four children. Their son Eli Sims Shorter II married Wileyna Lamar, heir to the S.S.S. Tonic Company (present-day S.S.S. Company) founded in 1826. The couple built a lavish home, now known as the Shorter Mansion, in Eufaula, and it now houses the Eufaula Historical Museum and the Eufaula Heritage Association.

Shorter had an early interest in politics and was a delegate to the June 1849 Democratic state convention in Montgomery, Montgomery County. He, along with strident slavery advocate William Lowndes Yancey and others, helped to secure the successful nomination of Alabama Supreme Court justice Henry W. Collier of Tuscaloosa County as governor. (They felt Collier would push the Democratic Party closer to a states’ rights political platform, but he was a moderate and did not support outright secession as governor.) Shorter’s reputation for oratory, strong stance on states’ rights, and expertise in legal and agricultural practices in the state caught the attention of many. Shorter and fellow Democratic leaders in Barbour County who favored states’ rights and secession were referred to as the “Eufaula Regency.” This group of men, consisting mostly of Eufaula lawyers and professionals, were known not only for promoting secession in the 1850s but also for refusing any compromise aimed at preserving the Union.

Shorter was the leading candidate for Alabama’s Second Congressional District election in 1855. Traditionally, Barbour County had been a bastion for Whigs, thus preventing a Democrat from representing the district. However, redistricting in 1854 removed Montgomery, Macon, and Russell Counties from the district and added Butler and Lowndes Counties. This action benefitted the Eufaula Democrats who nominated Shorter. His opposition was American Party member and Union supporter Julius C. Alford, who had previously served in the Georgia House of Representatives. Alford attacked Shorter for favoring secession, but the influence of the Eufaula political leaders helped secure the election for Shorter. He won the race by a majority vote. Shorter’s first term was such a success that during his re-election campaign against Batt Patterson in 1857 he won every county in the district.

During his tenure, Shorter gained a reputation for arguing in support of slavery. In a speech given before the House of Representatives on April 9, 1856, Shorter denounced the Massachusetts Personal Liberty Bill, which nullified the Fugitive Slave Law in Massachusetts. He claimed that Massachusetts had violated the constitutional rights of the slave states with the bill. He did not claim that the Constitution protected slavery, because he believed that the states’ authority did that; rather, he argued that the Constitution protected the rights of the slaveholding states and also protected the Fugitive Slave Law nationwide. Two years later on December 17, 1858, in yet another fiery speech to the House of Representatives, Shorter, as a member of the House Indian Affairs Committee, demanded that the federal government compensate Georgia and Alabama for lands confiscated by the U.S. Army during the Second Creek War, again citing the Constitution’s protection of states’ rights. The Army had seized lands for the purposes of conducting war against the Creek Indians but never compensated the states or landholders for its use.

With private business matters requiring his attention, Shorter decided to retire and not seek reelection in 1859 after his second congressional term concluded. The seat was won by secessionist James L. Pugh. Shorter, however, remained active in politics. During the presidential campaign of 1860, he served as an elector for the Democratic Party, continuing to voice a strong stand in favor of slavery and states’ rights. After the American Civil War broke out, Shorter stepped away from politics to help organize Confederate troops in Alabama. He was elected colonel of the 18th Alabama Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which mustered into the Confederacy in 1861 in Auburn, then in Macon County. He was one of the officers that led the charge on the first day of fighting in April 1862 at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee. Military camp-life took its toll on Shorter, however, and after one year in the Army he contracted typhoid fever and was forced to retire on May 10, 1862. Shorter was then sent to Richmond, Virginia, by his brother, John, the governor of Alabama, to aid the Confederate secretary of war on the defenses of Alabama and Florida. At the conclusion of the war, he returned to Eufaula, where he continued his legal and agricultural pursuits and served as president of the Vicksburg and Brunswick Railroad.

During the 1868 presidential campaign, Shorter re-entered politics and used his oratorical talents on behalf of the Democratic nominee, former New York governor Horatio Seymour, in the northwestern states. Former Union general Ulysses S. Grant, the Republican nominee won the election, however. Shorter also played a role during the presidential election of 1876. He campaigned in Indiana for that state’s governor, Thomas A. Hendricks, who had promised Shorter a cabinet seat if he was elected. Shorter then served as an Alabama delegate for the 1876 Democratic National Convention when Samuel Tilden, governor of New York, was nominated for president over Hendricks, who became his running mate. Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio lost the popular vote but defeated Tilden in the Electoral College tally by one vote.

At the peak of his career, tragedy struck Eli Shorter in 1877, when his youngest son William died. Eli never recovered from this loss. He died in Eufaula on April 29, 1879. In addition to his illustrious political career, Shorter was a Knights Templar Freemason and an instrumental figure among Alabama Baptists, having served as president of the Baptist State Convention. He is buried at Fairview Cemetery in Eufaula.

Additional Resources

Bunn, Mike. The Eufaula Regency: Alabama’s Most Celebrated Secessionist Faction. Eufaula: Eufaula Heritage Association, 2009.

Dorman, Lewy. Party Politics in Alabama from 1850 Through 1860. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

Thornton, J. Mills, III. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.