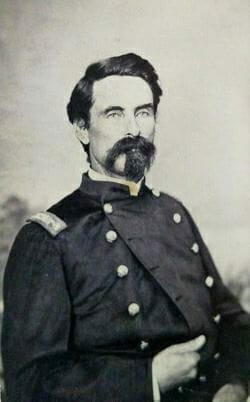

John Benton Callis

John Benton Callis (1828-1898) briefly represented Alabama’s Fifth Congressional District from 1868 to 1869 as a Republican during the Reconstruction era. He served as an officer in the U.S. Army during the Civil War and was assigned to Alabama’s Freedmen’s Bureau in the years immediately after the war. He is most remembered outside the state for his service in the Civil War, fighting in a number of significant battles, including such pivotal engagements as Antietam and Gettysburg.

John Benton Callis

Callis was born on January 3, 1828, in Fayetteville, North Carolina, to Henry and Christina Callis; he had two sisters. The family of pioneer farmers moved to Carroll County, Tennessee, in 1834 and then to Grant County, Wisconsin, in 1840. Callis attended the local common schools and then studied medicine for three years but decided not to become a physician. In 1849, he and an associate in Minnesota contracted to build Fort Marcy, a frontier outpost for the Army. It later became known as Fort Gaines and then Fort Ripley and grew from a military institution to a small city. Callis then tried his luck at mining for gold in California in 1851 and eventually settled into the mercantile trade. He also spent some time traveling in Central America, where he worked on a plantation, and then returned to the mercantile business in Wisconsin. There, in Lancaster City, Callis made his first foray into politics, serving as the city treasurer from 1854 to 1858. In 1855, he married Lancaster resident Mattie Barnett, with whom he would have five children.

John Benton Callis

Callis was born on January 3, 1828, in Fayetteville, North Carolina, to Henry and Christina Callis; he had two sisters. The family of pioneer farmers moved to Carroll County, Tennessee, in 1834 and then to Grant County, Wisconsin, in 1840. Callis attended the local common schools and then studied medicine for three years but decided not to become a physician. In 1849, he and an associate in Minnesota contracted to build Fort Marcy, a frontier outpost for the Army. It later became known as Fort Gaines and then Fort Ripley and grew from a military institution to a small city. Callis then tried his luck at mining for gold in California in 1851 and eventually settled into the mercantile trade. He also spent some time traveling in Central America, where he worked on a plantation, and then returned to the mercantile business in Wisconsin. There, in Lancaster City, Callis made his first foray into politics, serving as the city treasurer from 1854 to 1858. In 1855, he married Lancaster resident Mattie Barnett, with whom he would have five children.

A member of the Grant County militia, Callis served at the rank of lieutenant. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, he then began a distinguished service by raising a company and becoming captain of Company F, 7th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment, which was incorporated into the so-called “Iron Brigade,” in the Army of the Potomac. The Iron Brigade fought in some of the most significant battles in Virginia and at Gettysburg in Pennsylvania and gained notoriety for its fighting ability and high rate of casualties. During the first day of fighting at Bull Run in August 1862, all of the field officers outranking Callis were killed or forced from the field, leaving him in charge of the regiment. He retained command of the regiment and led it into battle at Fredericksburg and Antietam. By early 1863, he had been promoted to the rank of major and was quickly promoted again to lieutenant colonel before leading the regiment at the Battle of Chancellorsville. On the first day of battle at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863, Callis suffered minor wounds but held his post and took part in the charge that resulted in the capture of the Confederacy’s Gen. James J. Archer and much of his brigade; the Iron Brigade notably aided in helping to delay the Confederate advance. Later that day, Callis was shot in the chest, with the ball damaging both his liver and a lung. He remained on the field for the next 43 hours, briefly becoming a prisoner under the watch of a guard selected by Confederate general Jubal Early; the ball forever remained in his lung. Callis was finally taken to the home of a local woman caring for the wounded and his wife arrived three weeks later to return him to Wisconsin. He was released from duty on December 24, 1863, because of the severity of his wounds.

Once well enough to return to civilian life, Callis purchased a flour mill. Feeling restless, he joined the Veterans Reserve Corps on May 24, 1864, and was sent to Washington, D.C., to serve as military superintendent of the War Department. He saw action again in July 1864 during Gen. Jubal Early’s raid on Washington, D.C. On December 18, 1865, he was made a brigadier general for his meritorious service. Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, assigned Callis to the North Alabama District in Huntsville, Madison County, under the title of sub-assistant commissioner. He was tasked with organizing schools for emancipated slaves throughout his 16-county jurisdiction. He also sought to correct mishandling of funds by his predecessor and lobbied for a more equal distribution of government rations to freedmen. Callis worked to achieve friendly relations with the local businessmen and planters of Madison County. A number of his letters boast favorable relations with prominent southerners such as former Confederate secretary of war Leroy Pope Walker. Indeed, his personal correspondence offers an interesting insight into Reconstruction-era Alabama. He notes that good relations between bureau officials and locals were often the exception, however, having observed growing enmity following the passage of civil rights legislation. His official correspondences with his superiors also note his inability to stop violence against African Americans and the unwillingness of local authorities to prosecute assault cases.

During the election of 1868, Callis set his sights on Alabama’s Fifth Congressional seat. The struggle for the Republican nomination was a bitter one, with Callis losing to Joseph W. Burke, who was less supportive of rights for African Americans. Callis then ran as an independent and was able to rally nearly all of the newly enfranchised African Americans to his side and benefited from many white Alabamians boycotting the election in protest because they viewed most of the candidates as occupiers or collaborators with the occupying federal forces. He won easily, but his victory was contested because at the time of the election he did not reside in Alabama, having been ordered to Nashville by his superiors. The Committee on Elections, however, ruled that his credentials were in order and he was sworn in as the district’s representative. He was one of four Freedmen’s Bureau agents who were elected as Republicans to the Alabama delegation.

Though brief, being only 224 days, Callis’s term was an active one. He served on the Committee on Enrolled Bills and introduced legislation aimed at establishing mail routes in the state. He also lobbied for the return of voting rights to southerners and introduced a bill granting a $5 million-dollar loan to the New Orleans & Selma Railroad and Immigrant Association. Callis is sometimes attributed as the author of the first bill aimed at investigating the Ku Klux Klan, but it failed in the Senate. Callis chose not to seek reelection and left office on March 3, 1869. He was succeeded by Democrat Peter Myndert Dox.

Callis returned to Wisconsin and worked in real estate and the insurance business. In 1874, he won a seat as a Democrat in the State Assembly, where he chaired the Committee on Incorporations and on State Lands. Callis was active in the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) and the Iron Brigade Association, both veterans’ organizations. He spoke highly of veterans on both sides of the Civil War and in interviews was conciliatory toward Confederate soldiers and called for an end to lingering bitterness. He served as a mentor to his nephew George Barnett, who was an innovator in amphibious warfare and commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps during World War I. Callis died on September 24, 1898, and was buried in Hillside Cemetery in Lancaster, Wisconsin.

Additional Resources

Barnett, George. George Barnett, Marine Corps Commandant: A Memoir 1877- 1923. Jefferson, N.C..: McFarland & Company, 2004.

Shapiro, Norman. “John Benton Callis: Madison County’s Republican Congressman.” Huntsville Historical Review Spring 29 (Spring-Summer 2004): 7-56.