Alabama on Wheels

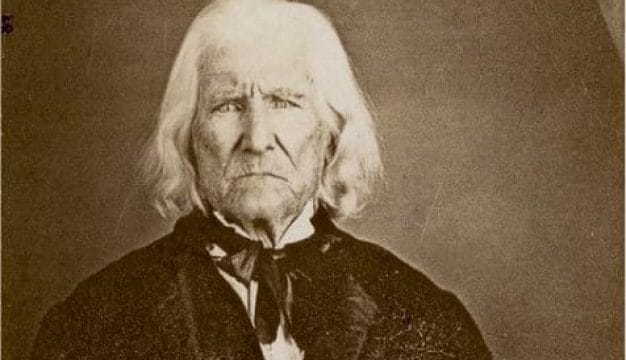

Reuben F. Kolb

“Alabama on Wheels” was an attempt by Alabama Agriculture Commissioner Reuben F. Kolb and other state leaders to attract immigrants to Alabama from prosperous northern states to displace black farmers from the most fertile portions of the state. It was part of a larger movement during the New South Era to attract settlers from Europe and invigorate an Alabama economy that was lagging behind other southern states. The promotional effort took the form of outfitting several railway cars with exhibits, showing the manifold benefits of settling in Alabama, that were sent on a journey of more than 4,000 miles through nine states from August to October of 1888. The unwillingness of the state and private donors to provide follow-up promotions and the persisting image of Alabama as poor, violent, racist, and disease-ridden ultimately doomed Kolb’s efforts.

Reuben F. Kolb

“Alabama on Wheels” was an attempt by Alabama Agriculture Commissioner Reuben F. Kolb and other state leaders to attract immigrants to Alabama from prosperous northern states to displace black farmers from the most fertile portions of the state. It was part of a larger movement during the New South Era to attract settlers from Europe and invigorate an Alabama economy that was lagging behind other southern states. The promotional effort took the form of outfitting several railway cars with exhibits, showing the manifold benefits of settling in Alabama, that were sent on a journey of more than 4,000 miles through nine states from August to October of 1888. The unwillingness of the state and private donors to provide follow-up promotions and the persisting image of Alabama as poor, violent, racist, and disease-ridden ultimately doomed Kolb’s efforts.

The impetus for this enterprise emerged during the New South Era as southern farmers increasingly recognized the prosperity of lands in the upper Midwest (called the “Northwest” at the time) settled largely by European immigrants. It was also spurred by the writings and speeches of Atlanta Constitution editor Henry Grady, who envisioned an economically invigorated New South. Reflecting the white supremacist views of the time that recently emancipated African Americans were unreliable, various state agencies, land and railroad companies, and innumerable immigration societies throughout the South, with Grady and other editors in the forefront, initiated efforts during the 1880s to attract whites from the North and from Europe.

The topic of immigration was not new to Alabama. After the Civil War, industry faced increasing labor needs and plantation owners no longer had access to enforced labor in the form of slaves. Many African Americans, and a large number of white workers, headed to urban and industrial areas around Birmingham and in other states. Indeed, Alabama’s Constitution of 1875 specifically encouraged immigration and created a Commissioner of Immigration. Some landowners and politicians, however, did not want to encourage immigrants, fearing that they would bring radical political ideas, such as anarchism and communism.

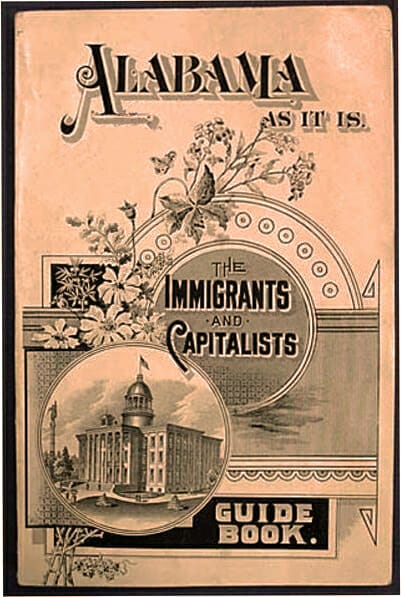

Alabama As It Is Cover

In Alabama, the foremost proponent of immigration was Kolb, an agriculturist known for his Populist viewpoint. He was appointed Agriculture Commissioner in 1887 by Gov. Thomas Seay, who also viewed immigration as a possible solution to Alabama’s economic ills. The immigration commission foundered for lack of financial support and in face of the prevalent isolationism, however. In 1888, Kolb found his motivation renewed after reading the reprinted edition of Benjamin Riley’s Alabama As It Is or, The Immigrants and Capitalists Guide Book to Alabama. In April, accompanied by civic leaders from Decatur, Sheffield, and Opelika, Kolb visited nearly 70 towns in Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan, distributed promotional literature to enthusiastic crowds, and attended an immigration convention in North Carolina. Encouraged by the success of his tour, Kolb promised that if the legislature would appropriate $10,000 a year, he would attract 10,000 people yearly to Alabama.

Alabama As It Is Cover

In Alabama, the foremost proponent of immigration was Kolb, an agriculturist known for his Populist viewpoint. He was appointed Agriculture Commissioner in 1887 by Gov. Thomas Seay, who also viewed immigration as a possible solution to Alabama’s economic ills. The immigration commission foundered for lack of financial support and in face of the prevalent isolationism, however. In 1888, Kolb found his motivation renewed after reading the reprinted edition of Benjamin Riley’s Alabama As It Is or, The Immigrants and Capitalists Guide Book to Alabama. In April, accompanied by civic leaders from Decatur, Sheffield, and Opelika, Kolb visited nearly 70 towns in Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan, distributed promotional literature to enthusiastic crowds, and attended an immigration convention in North Carolina. Encouraged by the success of his tour, Kolb promised that if the legislature would appropriate $10,000 a year, he would attract 10,000 people yearly to Alabama.

Kolb soon found moral and financial support from numerous municipalities, an offer of cheap land from the Gulf and Chicago Air Line Railway, funding from the Central Railroad of Georgia, and two furnished cars from the Louisville and Nashville Railroad for a more ambitious promotional journey to the North. One of the railway cars was fitted with exhibits of agricultural, timber, and mineral resources. It was divided into eight sections constructed of native pine, polished with oil, and emblazoned outside with the phrase “Alabama’s Matchless Resources.”

On August 14, “Alabama on Wheels” departed from Union Station in Montgomery. Its entourage, which included representatives from 17 cities and counties in the state, projected a broad view of the state’s potential. Everywhere on their journey there appeared to be more farmers than land and at virtually every stop thousands visited the train. A festive atmosphere prevailed as it made its way over the next two months through such cities as Evansville, Indiana; Peoria, Illinois; Sioux City, Iowa; St. Paul, Minnesota; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Kalamazoo, Michigan; Columbus, Ohio; and Louisville, Kentucky.

The Alabamians were gratified by their warm reception, and they were also impressed by the prosperity and industrious attitude of northerners, seemingly in stark contrast to conditions in the South, where decades of rule by plantation and business elites and the devastation of war had demoralized the populace. The visitors found progressive views toward institutions of learning and charitable organizations and found willingness to spend tax dollars on assisting the young, unfortunate, and helpless. On September 16, Kolb reported to Gov. Seay that often as many as 6,000 or 7,000 people passed through the exhibit car daily. This enthusiasm led him to believe that thousands of immigrants would soon be flocking to the South.

The Alabama legislature, however, had thus far failed to make any appropriation to fund the effort. In a related issue, the expedition’s correspondent Chappell Cory noted that the legislature failed to fund public education anywhere near the level he had observed in Wisconsin. Then in late September and October, dozens of people were sickened and 35 people (including five doctors) died in an outbreak of yellow fever in Decatur, Morgan County, prompting headlines in the Chicago Tribune that the city was almost depopulated and people were fleeing the South from fear of disease. Prevailing images of Alabama in the North and Midwest that projected the state as backwards and hostile to outsiders proved difficult to dispel.

Despite a shortage of funds, the expedition completed the remainder of its 4,000-mile itinerary and found a warm welcome in Montgomery on October 17. Its ultimate success, however, would depend on whether the momentum for supporting immigration could be sustained. To this end Kolb, supported by the governor, appealed to the General Assembly in November for $25,000 and in December 1888 organized the Southern Interstate Immigration Convention, which hosted an interstate immigration convention in Montgomery attended by 600 delegates. Although “Alabama on Wheels” was much discussed and admired, an immigration appropriations bill for $5,000 barely passed the Senate in February 1889 and was never considered by the House. Despite subsequent claims by Kolb that more than 1,000 people had already come to the state, Census figures indicate that its native-born population had in fact risen from 98.7 percent in 1860 to 99 percent in 1890.

Although “Alabama on Wheels” garnered praise throughout the North and presented a good image of the state, its efforts were doomed by cultural realities and perceptions in the North and South alike. Efforts to displace emancipated blacks with white settlers were ultimately dashed by the racist proclivities it was designed to perpetuate. Given the xenophobic attitude prevalent in the South, fears by white immigrant laborers that they would be relegated to a social position similar to that of blacks prevailed; that they would become virtual outcasts in a land where they were invited to make their home.

Additional Resources

Berthoff, Roland T. “Southern Attitudes Toward Immigration, 1865-1914.” The Journal of Southern History 17 (August 1951): 328-60.

Fleming, Walter L. “Immigration to the Southern States.” Political Science Quarterly 20 (June 1905): 276-97.

Going, Allen J. Bourbon Democracy in Alabama, 1874-1890. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1951.

Loewenberg, Bert James. “Efforts of the South to Encourage Immigration, 1865-1900.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 33 (October 1934): 363-85.

Pruett, Katharine M., and John D. Fair. “Promoting a New South: Immigration, Racism, and ‘Alabama on Wheels.” Agricultural History 66 (Winter 1992): 19-41.

Riley, Benjamin F. Alabama As It Is: Or, The Immigrant’s and Capitalist’s Guide to Alabama. Atlanta: Constitution Publishing Co., 1888.

Rogers, William Warren. “Reuben Kolb: Agricultural Leader of the New South.” Agricultural History 32 (April 1958): 109-19.

Summersell, Charles Grayson. “A Life of Reuben F. Kolb.” M.A. thesis, University of Alabama, 1930.