Civilian Conservation Corps in Alabama

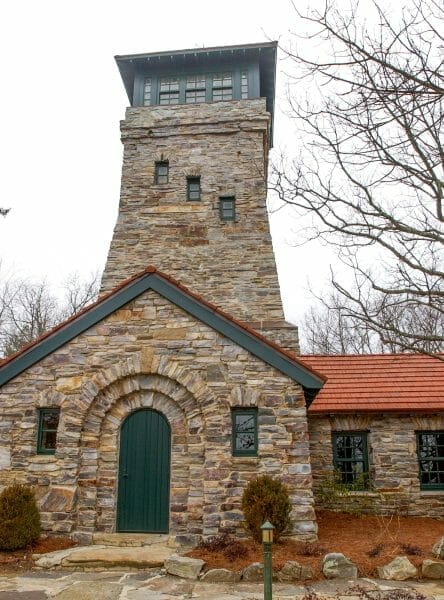

Bunker Tower

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) work program was established by Pres. Franklin Delano Roosevelt as part of his New Deal legislation in March 1933. The CCC’s main goals were to conserve and develop the natural resources of the United States while putting unemployed young, urban men to work during the Great Depression. In Alabama, the CCC established more than 40 camps across the state and initiated projects to improve the state’s forested lands, strengthen the forest-fire protection system, and aid in the development of new state park lands. The program conducted numerous projects around the state, including soil conservation and dam construction and waterway improvements. As in other states, the Alabama CCC also constructed numerous buildings and trails in many local and state parks, as well as in other locations in the state, that are still in use today.

Bunker Tower

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) work program was established by Pres. Franklin Delano Roosevelt as part of his New Deal legislation in March 1933. The CCC’s main goals were to conserve and develop the natural resources of the United States while putting unemployed young, urban men to work during the Great Depression. In Alabama, the CCC established more than 40 camps across the state and initiated projects to improve the state’s forested lands, strengthen the forest-fire protection system, and aid in the development of new state park lands. The program conducted numerous projects around the state, including soil conservation and dam construction and waterway improvements. As in other states, the Alabama CCC also constructed numerous buildings and trails in many local and state parks, as well as in other locations in the state, that are still in use today.

Between 1933 and 1942, an average of 30 CCC camps operated each year in Alabama, employing 66,837 men over nine years. By 1942, the CCC had built 1,800 miles of roads, 61 lookout towers, 490 bridges, and 188 buildings and strung 1,430 miles of telephone of lines across the state. The men constructed firebreaks, fought forest fires, and planted trees. They worked on soil erosion projects and helped to control insect epidemics, and also inventoried forest resources across the state. The CCC in Alabama constructed a permanent archaeological museum at Moundville, was responsible for the establishment or improvement of 12 state parks, and assisted with the development of the Natchez Trace Parkway.

Enrollment Policies

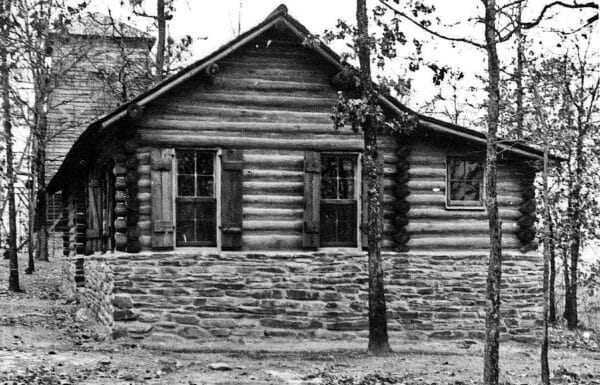

Weogufka Caretaker’s Cabin

The CCC program was a collaborative effort between various state and federal agencies. The U.S. Department of War administered the camps, and the National Park Service within the U.S. Department of the Interior and the Forest Service within the U.S. Department of Agriculture helped to develop and manage projects on federal land. State agencies provided resources and equipment for projects on land owned by the state and also assisted with projects on private land. The U.S. Department of Labor was responsible for enrolling men between the ages of 18 and 25 from families receiving public assistance. Men who signed up for the program enlisted for a minimum of six months and had the option to re-enlist for up to two years. For their work, they earned $30 per month. Of this amount, $25 was sent back to the worker’s family, and the CCC supplied the young men with food, clothing, medical care, and housing in camps administered by the U.S. Army.

Weogufka Caretaker’s Cabin

The CCC program was a collaborative effort between various state and federal agencies. The U.S. Department of War administered the camps, and the National Park Service within the U.S. Department of the Interior and the Forest Service within the U.S. Department of Agriculture helped to develop and manage projects on federal land. State agencies provided resources and equipment for projects on land owned by the state and also assisted with projects on private land. The U.S. Department of Labor was responsible for enrolling men between the ages of 18 and 25 from families receiving public assistance. Men who signed up for the program enlisted for a minimum of six months and had the option to re-enlist for up to two years. For their work, they earned $30 per month. Of this amount, $25 was sent back to the worker’s family, and the CCC supplied the young men with food, clothing, medical care, and housing in camps administered by the U.S. Army.

Unlike many programs created during the Depression, the CCC initially had a policy that banned discrimination based on race, color, or religious affiliation. Despite this, however, the deep-rooted systems of racism and segregation in Alabama and other states shaped the experience of African Americans in the CCC. Early on in Alabama, Thad Holt, the state director of relief, led the effort to enroll African Americans in the CCC. But many local all-white relief councils tried to prevent this from happening, and by June of 1933, only 776 Alabama African Americans had been enrolled, in comparison with approximately 4,500 whites. To quiet protests about enrolling black men, it became CCC policy that no black men were to be transported outside their state of origin. This policy did not end the tensions, however. As the result of unfounded racist fears that integrated camps would lead to violence between black and white men, the CCC was segregated after 1935 and remained so through 1942. State governors selected the location of the all-black camps. The program did slowly come to benefit a significant number of Alabama African Americans with the support of Gov. Bibb Graves, who helped develop one of the better-run CCC programs for African Americans in the country. The state hosted 17 all-black CCC companies, including three made up of black World War I veterans.

CCC Projects in Alabama

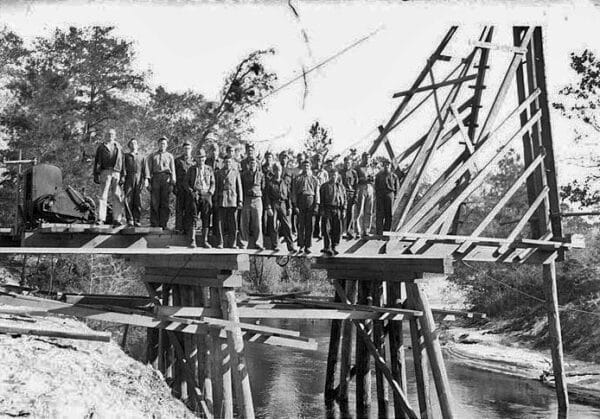

Bridge at Chunchula

Camps were located in close proximity to projects that were scattered throughout the state. Each camp housed approximately 200 men and contained an average of 24 buildings, including a kitchen and a mess hall, a recreation building, a school, an infirmary, and barracks. Military and technical staff had separate quarters. Before being assigned to their work camp, men spent ten days at a conditioning camp to improve the quality of their health, as many suffered from the ill-effects of malnutrition. Reserve officers from the U.S. Army administered the camps. Supervisors for individual projects were hired by the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture. Men were organized into sections of 25 and were led by a senior leader and assistant leader who took direct responsibility for their men on work assignments and in the barracks.

Bridge at Chunchula

Camps were located in close proximity to projects that were scattered throughout the state. Each camp housed approximately 200 men and contained an average of 24 buildings, including a kitchen and a mess hall, a recreation building, a school, an infirmary, and barracks. Military and technical staff had separate quarters. Before being assigned to their work camp, men spent ten days at a conditioning camp to improve the quality of their health, as many suffered from the ill-effects of malnutrition. Reserve officers from the U.S. Army administered the camps. Supervisors for individual projects were hired by the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture. Men were organized into sections of 25 and were led by a senior leader and assistant leader who took direct responsibility for their men on work assignments and in the barracks.

By September 1933, 18 CCC camps had been established in Alabama. Three were located in the Alabama National Forest (now William B. Bankhead National Forest), at the behest of Rep. Edward Almon of the Eighth Congressional District, to work on improving roads and on reforestation. Men from six camps worked on private forest assignments and two additional camps worked on private soil erosion projects. The CCC also operated five state forest camps, one state park camp, and one army camp. Other camps followed, and by September 1934, there were 30 CCC camps in the state, including five focusing on soil erosion, park development, and timber improvement overseen by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

Improving Farms and Forests

Soil erosion was a major focus of CCC efforts in Alabama, and the agency worked with a variety of other state and federal agencies on projects related to its prevention. During the 1920s, experts across the country recognized that soil erosion was an enormous problem for farmers. Therefore, on August 25, 1933, Roosevelt created the Soil Erosion Service (SES). The SES came to Alabama in 1934 and worked with the CCC to initiate projects such as those at Buck and Sandy Creek, which improved an area of 117,000 acres in Chambers and Tallapoosa Counties, respectively. Agents worked with farmers to implement such practices as crop rotation, contour plowing to follow natural topography, and terracing. They also taught farmers about the importance of cover crops to help protect topsoil, built erosion-controlling check dams, and planted trees on unused farmland. On April 27, 1935, the SES became the Soil Conservation Service (SCS), with state headquarters for the SCS being established at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (present-day Auburn University) in Lee County.

Forest Restoration

Improving Alabama’s forests was another major focus of the projects. In a state that had seen widespread deforestation from commercial logging and clearing land for agriculture, there was a clear need for programs to improve the management of forest resources. CCC workers across the state helped build necessary infrastructure for managing forests, including roads, firebreaks, and bridges, as well as recreational facilities for public use. Two companies composed of African American veterans of World War I built a road to the top of Cheaha Mountain. Workers at Chunchula, in Mobile County, and in Brewton, Escambia County, constructed truck trails and firebreaks and worked on fire suppression and prevention projects on state lands. Other companies worked on private land on projects similar to the state forestry work being conducted at other camps so landowners could increase their output. Other companies, including an African American company in Clayton, worked on erosion control projects. Camps would continue to spread through Alabama to help prevent forest fires, construct roads, and build firebreaks until the CCC efforts came to an end.

Forest Restoration

Improving Alabama’s forests was another major focus of the projects. In a state that had seen widespread deforestation from commercial logging and clearing land for agriculture, there was a clear need for programs to improve the management of forest resources. CCC workers across the state helped build necessary infrastructure for managing forests, including roads, firebreaks, and bridges, as well as recreational facilities for public use. Two companies composed of African American veterans of World War I built a road to the top of Cheaha Mountain. Workers at Chunchula, in Mobile County, and in Brewton, Escambia County, constructed truck trails and firebreaks and worked on fire suppression and prevention projects on state lands. Other companies worked on private land on projects similar to the state forestry work being conducted at other camps so landowners could increase their output. Other companies, including an African American company in Clayton, worked on erosion control projects. Camps would continue to spread through Alabama to help prevent forest fires, construct roads, and build firebreaks until the CCC efforts came to an end.

Recreational Facilities

Caney Creek Falls in Bankhead National Forest

Other camps worked to improve public facilities in the growing number of state parks. Between 1930 and 1933, the state opened 12 of its 22 state parks. The companies that built the road to the top of Cheaha Mountain also developed facilities in the new Cheaha State Park (which would become part of the larger Talladega National Forest, designated in 1936). During the 1930s, the CCC also constructed Cheaha Lake, a stone bathhouse, stone cabins, Bunker Tower, and the Bald Rock Group Lodge. A CCC project in DeSoto State Park led to the construction of cabins, a lodge, and pavilions for public recreation. The state created these new parks to encourage recreation and to aid in the management of the state’s natural resources. The CCC also assisted with land management and recreational facility projects in the Bankhead National Forest (created in 1918) and the Conecuh National Forest (created in 1936). As a result of the work of the CCC and state agencies, by 1943 Alabama had more than nine million acres of forested land under the protection of the State Division of Forestry (present-day Alabama Forestry Commission). Because of better land management and forestry practices, the value of Alabama’s timber crop increased to an estimated $150 million annually.

Caney Creek Falls in Bankhead National Forest

Other camps worked to improve public facilities in the growing number of state parks. Between 1930 and 1933, the state opened 12 of its 22 state parks. The companies that built the road to the top of Cheaha Mountain also developed facilities in the new Cheaha State Park (which would become part of the larger Talladega National Forest, designated in 1936). During the 1930s, the CCC also constructed Cheaha Lake, a stone bathhouse, stone cabins, Bunker Tower, and the Bald Rock Group Lodge. A CCC project in DeSoto State Park led to the construction of cabins, a lodge, and pavilions for public recreation. The state created these new parks to encourage recreation and to aid in the management of the state’s natural resources. The CCC also assisted with land management and recreational facility projects in the Bankhead National Forest (created in 1918) and the Conecuh National Forest (created in 1936). As a result of the work of the CCC and state agencies, by 1943 Alabama had more than nine million acres of forested land under the protection of the State Division of Forestry (present-day Alabama Forestry Commission). Because of better land management and forestry practices, the value of Alabama’s timber crop increased to an estimated $150 million annually.

Roosevelt Visits Wilson Dam

On May 18, 1933, Congress authorized the creation of the TVA. The agency’s goals of generating electricity, managing flooding along the Tennessee River, improving navigation, and improving soil quality complemented the work being carried out by the CCC in other parts of the state. Additionally, the TVA began reforestation projects, soil-erosion control projects, and the construction of recreational facilities along the riverfront, with the CCC contributing labor for these projects. On October 13, 1933, 1,000 CCC enrollees arrived in the Muscle Shoals area, the center of much early TVA work because of Wilson Dam, the first major dam on the Tennessee River, which was acquired by the TVA in 1933. The first CCC company sent to Muscle Shoals began work on a variety of projects, constructing a park on the banks of the Tennessee River and establishing a nursery and establishing a game-breeding refuge. The company also constructed several bridges and rock structures, including fountains, pavilions, stairs on hiking trails, overlooks, and buildings on TVA land. At the end of 1937, the CCC companies withdrew and the TVA assumed responsibility for the trail system, park areas, and other facilities.

Roosevelt Visits Wilson Dam

On May 18, 1933, Congress authorized the creation of the TVA. The agency’s goals of generating electricity, managing flooding along the Tennessee River, improving navigation, and improving soil quality complemented the work being carried out by the CCC in other parts of the state. Additionally, the TVA began reforestation projects, soil-erosion control projects, and the construction of recreational facilities along the riverfront, with the CCC contributing labor for these projects. On October 13, 1933, 1,000 CCC enrollees arrived in the Muscle Shoals area, the center of much early TVA work because of Wilson Dam, the first major dam on the Tennessee River, which was acquired by the TVA in 1933. The first CCC company sent to Muscle Shoals began work on a variety of projects, constructing a park on the banks of the Tennessee River and establishing a nursery and establishing a game-breeding refuge. The company also constructed several bridges and rock structures, including fountains, pavilions, stairs on hiking trails, overlooks, and buildings on TVA land. At the end of 1937, the CCC companies withdrew and the TVA assumed responsibility for the trail system, park areas, and other facilities.

CCC Legacy in Alabama

CCC Education Building

The CCC did more than just improve infrastructure and plant trees. The CCC also helped to expose young men to new places and to new ideas. Many men from Alabama served in other states that were part of the Fourth Corps Area (the Southeast) and other men came to Alabama from other parts of the country, especially during the winter in northern camps. Many CCC enrollees gained access to educational opportunities that they otherwise would not have had access to. Half of the Alabama CCC enrollees had left school before the eighth grade, and a smaller number had never had any classroom experience. Across the country, more than 40,000 young men learned to read and write through the CCC and many earned a high school diploma. Others learned skills as diverse as radio code, typing, and woodworking. The young men took important mechanical, agricultural, and construction skills home to their communities or into the military when World War II broke out. Overall, the CCC helped to improve the lives of the young men who served while benefitting the state in ways that Alabamians continue to enjoy today.

CCC Education Building

The CCC did more than just improve infrastructure and plant trees. The CCC also helped to expose young men to new places and to new ideas. Many men from Alabama served in other states that were part of the Fourth Corps Area (the Southeast) and other men came to Alabama from other parts of the country, especially during the winter in northern camps. Many CCC enrollees gained access to educational opportunities that they otherwise would not have had access to. Half of the Alabama CCC enrollees had left school before the eighth grade, and a smaller number had never had any classroom experience. Across the country, more than 40,000 young men learned to read and write through the CCC and many earned a high school diploma. Others learned skills as diverse as radio code, typing, and woodworking. The young men took important mechanical, agricultural, and construction skills home to their communities or into the military when World War II broke out. Overall, the CCC helped to improve the lives of the young men who served while benefitting the state in ways that Alabamians continue to enjoy today.

Further Reading

- Pasquill, Robert G. The Civilian Conservation Corps in Alabama, 1933-1942: A Great and Lasting Good. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

- Pasquill, Robert G. “Protecting Alabama’s Forests: The Civilian Conservation Corps Projects in State and Private Forests 1933-1942”; http://www.forestry.alabama.gov/.